Written by Max Naylor

You don’t normally go into a documentary as a blank slate, a sincerely pure vessel. It is the nature of the medium that draws you in. You’re interested in the rule of Idi Amin, or you really have always wondered about the font Helvetica, and the opportunity to learn more about a subject, perhaps a subject you didn’t even realize sparked your interest until the moment you read the title, piques your interest. It is therefore a rare opportunity to watch a film with almost no preliminary opinion or knowledge of the subject matter, and really affords the audience a unique perspective on the concepts presented. As an example, I once saw Invictus as part of a double-feature having no idea of the subject matter beforehand. You try getting “South African Rugby” out of a title like that. It’s a tricky bridge to cross, and all the more surprising and delightful for it.

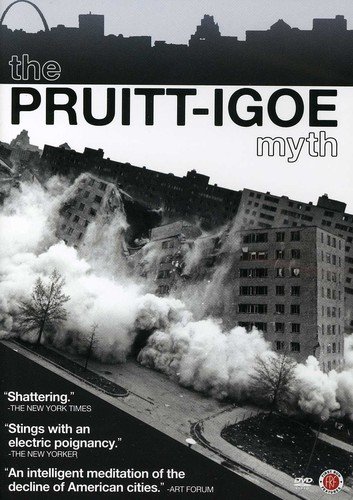

I wouldn’t believe there would be a large contingent of people who would be terribly familiar with the subject of The Pruitt-Igoe Myth, and perhaps even fewer who would be able to parse the film’s content from its cryptic title. Because of this, the film is an absolute treat for anyone who enjoys a well-presented, intriguing documentary, regardless of the subject matter. I was absolutely amazed by how interested I was in St. Louis’ mid-20th-century urban-renewal program, which itself serves as a microcosm of the nation’s industrial development at the time, and the tremendous social blow that was dealt due to the ill-fated undertaking.

Focusing primarily on the eponymous housing development in St. Louis, the film endeavors to unearth the devastating social and economic impact the collapse of the originally humanitarian project had on those who inhabited the housing development. It is amazing just how much archival footage the filmmakers were able to unearth and incorporate, especially considering the concept of the complete collapse of what seems to have begun as an almost charitable task does not hold such a large footprint in our national memory. It’s a strange, almost eerie moment when a film reel from the mid-’50s refers to a building as a housing “project,” with no negative connotation in the narrator’s voice, and to see, in genuine, original photography, the recorded decline of these buildings from thriving, majestic “solutions” to the problem of the slums, to what essentially became a larger, more dangerous version of the very disastrous living conditions they were designed to replace.

It’s an interesting moment in time for this film to be released. All over television and film there seem to be so many period pieces being released that harkens back to a more honored, nostalgic time in our history. Mad Men and the short-lived Pan-Am, while certainly not portrayed as utopian societies, are nonetheless presented as glamorous and sophisticated. Meanwhile, the Occupy movement continues across the country, perhaps with less fervor than in the weeks past, but still in our conscious. This film arrives at an extremely appropriate time and manages to go beyond simply displaying the struggle of those subjected to the vacuum of rapid surburbanization in the ’50s and ’60s, and becomes something of a time capsule of the current zeitgeist. It’s a way to step back and consider the consequences of unfettered avarice and capitalism in the face of civic and social strife.

However, even without the histrionic social commentary on my part, the film is an absolutely fascinating documentary. I would highly recommend it to anyone who is interested in the interesting, and would ask that anyone considering this film for a viewing night would forgive my use of the word “zeitgeist,” which should never be uttered in cold blood. Watch this film. I guarantee, you will learn something.