Written by Ram Venkat Srikar

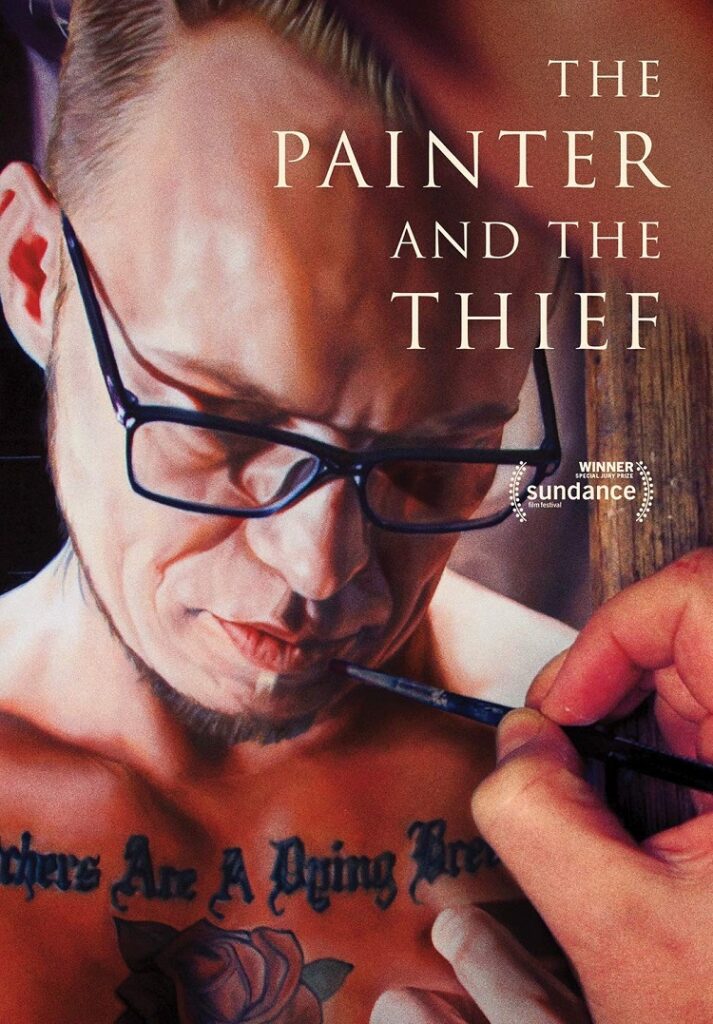

Benjamin Ree’s The Painter and the Thief is a musing, contemplative portraiture of juxtaposing individuals, that captures the gentle deliquesce of dissimilitude between them. The Norwegian documentary finds its fons et origo in the pilfering of Barbora Kysilkova’s – the eponymous painter – paintings, and swiftly molds into a vignette of her relationship with Karl-Bertil Nordland, the thief. The film is neither about unearthing the whereabouts of the stolen painting, nor about finding the burglars involved in the subject. It pivots around the idea of empathizing with the adversary, trying to learn and apprehend the latter and his/her inducement, thereby attaining cognitive satisfaction. I believe the human tendency strives to make head or tail of why someone would do something to us, when the action has stark consequences. This propensity enjoins Kysilkova to peek into the thorny psyche of Nordland, and what follows is the flourishing of a bond that’s mutually rewarding to these contrasting humans.

Although the camera discretely pursues these people through numerous, intimate moments in their lives, the first rendezvous is delineated through a series of their portraits, as their tête-à-tête is overheard in the background. The paintings play a fountainhead and driving factor of this evolving relationship, such is the gravity of these paintings in the film. The film’s most profound and honest moment has Nordland breaking into tears after catching sight of Kysilkova’s portrait of him. The purity of the moment derives from the deep glance into Nordland’s life before he became the thief, and the film never qualms itself while bestowing sensitive information. The troubled childhood that catalyzed his descent into drug-addiction, is never availed as a victim card, but is seamlessly woven to represent the root of his present self. By the same token, focusing on Kysilkova’s perturbing past relationship and the afflictions she is confronted with on the financial front, make this film as much about her personal life, as much it is about her relationship with Nordland.

The therapeutic mood it possesses, coupled with an unavowed tension (read: sexual, at times) between the leads makes the documentary seem like a vignette of one of the most uncommon love stories. Kysilkova, when questioned by her boyfriend, Øystein, regarding the morality of her relationship with a perplexing person like Norland, she ripostes that a naked soul is how she identified him during their initial interaction. Into the bargain, Kysilkova tells that she didn’t envisage the relationship to transmogrify into what it has come to be. I earnestly wonder whether Ree foresee this metamorphosis when he set out. In long stretches of narrative which are dedicated to the progress of each individual’s life, Norland and Kysilkova divulge attributes from each others’ past, betokening the intricacy of their relationship. To cut a long story short, it’s beautiful and gladdening.

What commences as a simple film about a thief and a painter, transmutes into a memorable, atypical tale of friendship, redemption, and solicitude.