Written by Kristen Lopez

I entered the theater with feelings of doubt prior to watching Nicolas Winding Refn’s The Neon Demon. The one-two punch that was Bronson and Drive led to the utter train wreck of Refn’s Ryan Gosling follow-up, Only God Forgives, so the director is 2-1 in my book, and critics division on Neon Demon is as wide as our current political party lines. Three critics walked out before the film was over and audience members were shouting at the screen. When the lights went up, I was left confused. Was this a prestige picture by a director touted as a “revolutionary,” or a midnight screening of Pink Flamingos? Had I just witnessed the most entertaining mess of the year, or a garbage film touting itself as a feminist call to arms? Were the two things mutually exclusive?

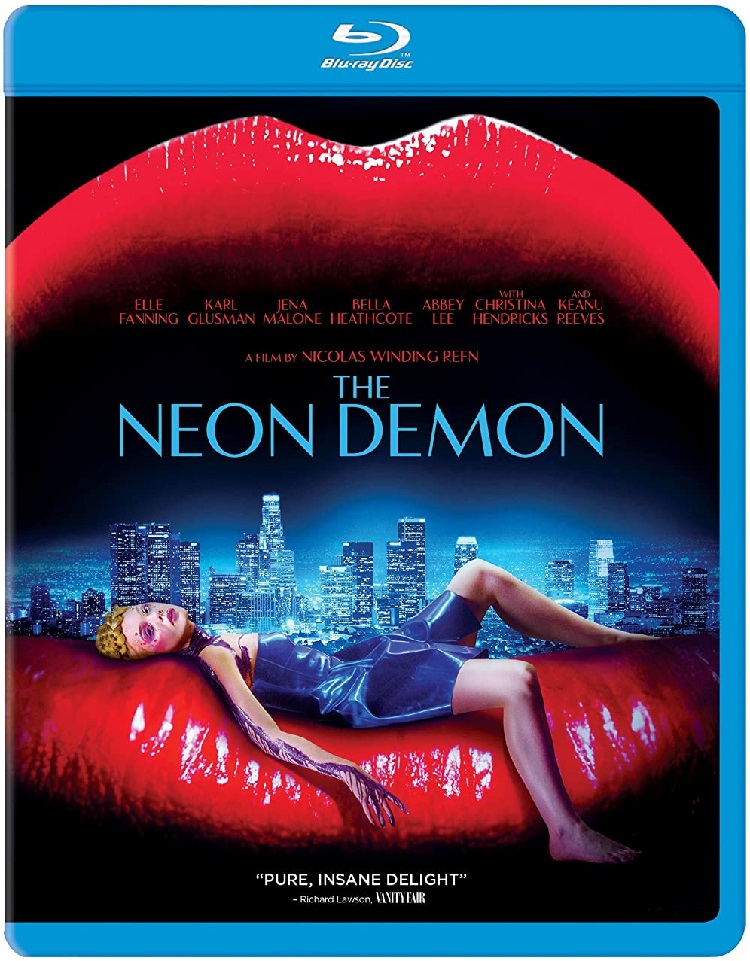

Jesse (Elle Fanning) travels to Los Angeles to become a model, but soon discovers everyone wants a pound of her flesh, whether she likes it or not.

In 1982 Julie Kristeva coined “the abject,” loosely defined as something that threatens our sense of cleanliness and/or reminds us of our mortality. It’s generally connected with horrible things like vomit which happen as a response to the breakdown between ourselves and the other. Now, all that mumbo jumbo I didn’t think I’d need after college is all found within The Neon Demon which revels in the blood, guts, and necrophilia as much as it does the glitter and paint thrown at the screen. It is this attraction to the disgusting that probably turned many critics off in my screening, but also crafts an allure around the film itself, this disgusting surreality keeps the audience questioning what’s happening, and ultimately leaves the ending to be so on the nose that it’s beaten into the face with a sledgehammer.

Jesse is a small town girl living in a lonely world, to quote Journey, who travels to L.A. because as Christina Hendricks’ Jan says, a guy told her she was pretty. And Jesse is definitely pretty….beautiful, in fact. It also helps that she’s young, just 16, and a virgin which creates a perfect storm where literally everyone wants her or wants to be her. Refn himself has said he wrote the film with his wife and daughters in mind, as a means of exploring beauty and the culture that worships at its altar. Nearly all the females in this film are preternaturally beautiful, from Fanning’s Jesse to Bella Heathcoate and Abbey Lee as Jesse’s competition, but it is Fanning who stalks the runaway, and the film.

Winding Refn’s wears influences on a his trench coat with shades of David Lynch, various horror movies, and most prominently Andrzej Zulawski’s Possession included. But, unintentionally or not, the closest comparison with The Neon Demon is Paul Verhoven’s Showgirls, the smutty red-headed stepchild of cult classicdom. Showgirls and Neon Demon both have directors who aren’t particularly amenable to female characters, and, in the former’s case, is argued to be a midnight movie feminist parable. Like Showgirls‘ protagonist Nomi Malone, Jesse has people falling over themselves for her (or, in the men’s case, rising to attention) for reasons no one can articulate; both films see older, wiser veterans of the industry meet horrific ends, and critics’ opinions of Showgirls were as vitriolic as they are here. Even Neon Demon’s marketing campaign, with its emphasis on glitter and single words like “Envy” and “Obsession” recall the erotic thrillers – Verhoven’s film included – of the 1990s.

Looking away from The Neon Demon is impossible. Not only do the girls look picture perfect, but everything, from the fashion to the story draws you in and refuses to let go. Valley of the Dolls was an inspiration, and much of Neon Demon involves pointed discussions about the modeling industry, and the state of women in general. Jesse’s youth and sexuality make her a perfect victim for unscrupulous landlords (played by Keanu Reeves at his most disgusting) and a culture that flaunts teen sex without discussing the consequences; Desmond Harrington’s photographer is so directly a parallel of photographer Terry Richardson it could be slanderous.

But that’s not to say that claims surrounding Refn’s misogyny stick out like a big, ugly thumb (just like it does with Showgirls). Refn delights in the naked bodies of his female characters. One shower scene in particular plays like a 1980s teen boy’s wet dream while simultaneously promoting the concept of the lecherous lesbian. And the script is saying absolutely nothing new about the modeling industry or female sexuality. The other models Jesse meets make the Plastics from Mean Girls look like Girl Scouts, and everyone she comes in contact with either wants to have sex with her or kill her.

Yet I found myself laughing at the black humor buried within Refn’s screenplay (co-written by Mary Laws and Polly Stenham). Christina Hendricks arrives, similar to Ava Gardner’s cameo in another movie about models, The Sentinel, to dispense the wisdom we’ll watch Jesse disregard and it’s almost a direct comment on the concept of subtlety; Hendricks’ Jan tells Jesse to say she’s 19 because 18 is “too on the nose,” laughable considering the entire film is on the nose. Similarly, a modeling agent played by Alessandro Nivola has a grand speech that seems to be a direct indictment against pretention…and maybe that’s the entire point of the film? Honestly, I’m still unclear. But with literal meat markets, vampiric women, etc. it’s seems Refn’s aesthetic is to be as overt as possible as a means of making fun.

The rest of the cast is spectacularly attractive, both in terms of looks and acting talent. As much as Fanning sells the little girl lost, and ambitiously found (her speech on a diving board is so great in light of how short-lived her catharsis is), is overshadowed by Abbey Lee’s Sarah. More gorgeous than Fanning, if that’s possible, Lee’s quiet and disgusted at nearly everything, spouting lines with vitriol at everyone, which only makes them funnier (think Kim Walker’s performance in Heathers); “why would he want spoiled milk when he can have fresh meat?” On the opposite side is Bella Heathcoate as the plastic-surgery-obsessed Gigi, spouting lines that are probably ads on the E! network: “plastics is just good grooming.” Jena Malone draws the short end of the stick as Ruby, the character with the film’s most shocking sequence. Her motivations are murky, but Malone’s inviting smile and nice girl routine enhance the shock of her actions.

The Neon Demon is an ’80s teen film with art-house credentials. Its cliquish presentation of the modeling world has been done before, but never with such a John Waters-level of depravity. You can practically hear Winding Refn giggling as the blood and lip gloss splashes everywhere. As someone who wanted to break Only God Forgives into little pieces, I was mesmerized by The Neon Demon. Trash cinema has its appeal and it’s found in this film’s cold fashion and bleak humor. The misogyny is to be expected, and ultimately undoes anything passing for feminist Refn would want to convey, but if you’re of the group that adores cult classics and/or beautiful garbage, The Neon Demon is for you.

Trailer: