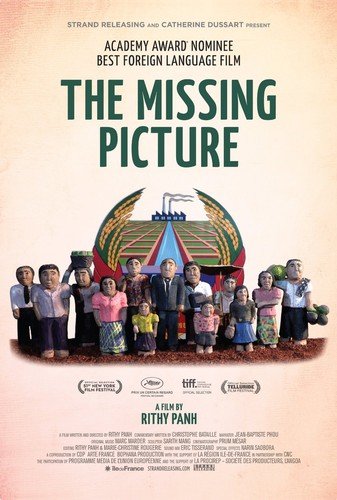

Directed and written by Cambodian filmmaker Rithy Panh, The Missing Picture is a fascinating and creative documentary. This 2013 picture was the Cambodian entry for the Best Foreign Language Oscar and secured the nomination. It also scooped the Un Certain Regard prize at Cannes.

Panh’s documentary is a deeply personal film. Using propaganda footage along with lovely recreations with sculpted clay figurines, he attempts to piece together the “missing footage” of his experiences in Cambodia when the Khmer Rouge ruled. Panh sifts through spools of celluloid and examines decaying film, but it washes away.

The English narration features Jean-Baptiste Phou as the narrative, while the French version makes use of Randal Douc. The narration begins describing Panh’s experiences with his family under the Khmer Rouge. Born in Phnom Penh in 1964 to a school teacher father, he recalls a life of education and music before the followers of the Communist Party of Kampuchea came.

After their arrival as ruling party in 1975, Panh’s family was expelled from Cambodia. He watched his family deteriorate, whether through overwork or malnutrition or other maladies. He watched Pol Pot, leader of the Khmer Rouge, fashion history in his own image. And he watched truth vanish with the passage of time.

Without accurate or truthful footage, Panh is effectively on his own to recreate his adolescence for the viewer. He handles this process in painstaking fashion, carving what seems like hundreds of clay figurines and placing them in different dioramas to depict his experiences in exile.

There is a surprisingly playfulness to the figurines, but they also show the rigours of experience and pain. They are sad. They appear to have lived, despite being inanimate objects, and they’ve surely suffered. Panh guides them through each chapter and verse and he can’t escape the grief. His poetic words can’t soften the blow.

The Missing Picture not only recreates history in unique fashion, it examines the idea of memory and refashions the art of depicting reality. As simple as his clay models may be, the events they depict are heartbreaking and raw. He notes that the Khmer Rouge must have filmed executions, for instance, and a clay figurine unbearably enters the frame with a blade.

Despite the potential for rage, it’s interesting to note how detached Panh is. There is sadness and there is catharsis, but there is also an element of acceptance. Perhaps the Dhammapada is instructive here when it states that “You are what you think. All that you are arises from your thoughts. With your thoughts you make your world.”

Panh has “made his world” out of tangible, extant clay. What he does with it is pass it on and with that insistent gesture, brought to life in the movie’s final frame, he makes the audience vow not to stand on ceremony. He has made his quest; it is time for us to make ours.

The Missing Picture is a fascinating and wrenching motion picture, but it is also beautiful and invigorating. Panh, who has clearly made his life’s work about coming to terms with his grief and his experiences, is a uniquely captivating filmmaker. And his latest piece, like the fascinating S-21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine before it, is incredible.