Tomu Uchida is not one of the big names of Japanese cinema in the West, even though he had been at the game from early in the 20th century – his first credits date to 1924. He’s made movies, excellent movies, throughout his career, but only recently have they been coming to light on home video releases.

That Uchida doesn’t have more recognition is a deep shame because, on the basis of this and a few other of his film available now in the West, he may be one of the Japanese greats, able to stand with his contemporaries Ichikawa, Ozu, and Mizoguchi.

His most famous movie in the English-speaking world might be Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji, a naturalistic road picture about the excesses of samurai privilege and the difficulty of personal relationships between the different castes of the Tokugawa shogunate. It was a humanistic and semi-realistic film.

The Mad Fox (1962) has no connection with realism whatsoever. Taking place somewhere in the 10th century, The Mad Fox is wildly stylistic, with enormous swathes of the film shot as if they were segments from a kabuki play, including narrative singing and stylized dance in place of realistic acting. The entire film is framed as seen from various aspects of the proscenium arch, with the angle of the camera constantly looking from above, as if the scenes we were watching had been painted on an ancient Japanese scroll, and we were looking at it spread out on a table.

Fittingly, the story is operatic in its scope: a master of prophecy takes in an adopted daughter, who will be able to help interpret an ancient scroll when the time comes right. Horrible omens occur, and the master reads part of the scroll: the shogun’s heir is in danger. The master’s wife is jealous, and has corrupted one of the master’s disciples. When the time comes for the scroll to be read, the final portion can only be interpreted by the master’s successor: either the corrupted disciple, Doman, or the shy Yusana, who is in love the adopted daughter, Sakaki.

The master’s wife conspires to have the master murdered, and Doman advanced into his position, and eventually has Yusana and Sakaki tortured when the ancient scroll turns out missing. Sakaki dies, and Yusana goes insane from grief, but escapes from the clutches of the wife. In his insanity, he comes across Sakaki’s twin sister, whom he believes to be Sakaki. Meanwhile, the shogun is given a prophecy about conceiving an heir that involves white foxes. So his men go out hunting, coincidentally where Yasuna is hiding out.

But white foxes are not just animals in The Mad Fox, but magical creatures, which can appear as people. The hunters shoot one that turns into an old woman, whom Yasuna rescues and takes back to her family. The youngest fox falls in love with Yasuna, against her family’s advice, and when they have the opportunity to rescue him from the hunters (who also want to capture Yasuna to reacquire his master’s prophetic scroll), the fox-girl takes the shape of Sakaki and comes to live with Yasuna as husband and wife.

It’s a simpler story than the precis of it seems, and also more emotionally affecting than the broad, rather ridiculous outlines would seem to allow. At every moment, the story is clear, as are the motivations of the characters. While the narrative is complicated, it’s never confusing. The visual style is ever-changing, but also ever in service of the story. It doesn’t show off, any more than a master musician is showing off when playing at a pace just at the edge of the audience’s comprehension: they’re just that good. So is Uchida.

I’ve only seen two other Uchida movies: Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji, and Miyamato Musashi, the first of a five-part movie series about the famous swordfighter. These were both largely naturalistic, straightforward films with complex characterizations, but that could be described as untaxing on the audiences patience (both were also excellent.) The Mad Fox is, comparatively, a bold, wildly stylistic endeavor. The majority of the film is shot from an overhead perspective. The opening narration takes place over an elaborately painted (and apparently enormous) scroll, going through the master’s history, and when the first live action shot appears I was still convinced it was part of the animation until live actors walked onto the set.

And then there are two large kabuki sequences of the film, one in the middle of the film and one forming the bulk of the final act. They even have curtains that are drawn across the screen, and sets that pivot in place like they were created for elaborate real-life plays. A major part of the final scenes involve a baby that is clearly a ceramic doll but that is treated as real by the characters. Once the shock of the surreal wears off, it feels exactly like watching a play, where the unrealistic aspects of the production are accepted as simply part of the show.

Describing The Mad Fox makes it seem like a mess, like a broken kaleidoscope of strange ideas. But in its presentation, it is beautiful, even mesmerizing. The color photography is painterly, the acting, while impossible to describe as realistic, is always appropriate to the pitch of the material. It’s operatic, lyrical, and fantastic… but also affecting. In lesser hands it would be a kind of delirious fantasia, interesting for its oddity. But Uchida’s assured direction turns it into nothing less than a masterpiece. With The Mad Fox (original Japanese title translates as Love, Thy Name Be Sorrow) and the few other films of Uchida’s available in the U.S., it’s not a stretch to say he could become a Japanese cinephile’s new favorite director.

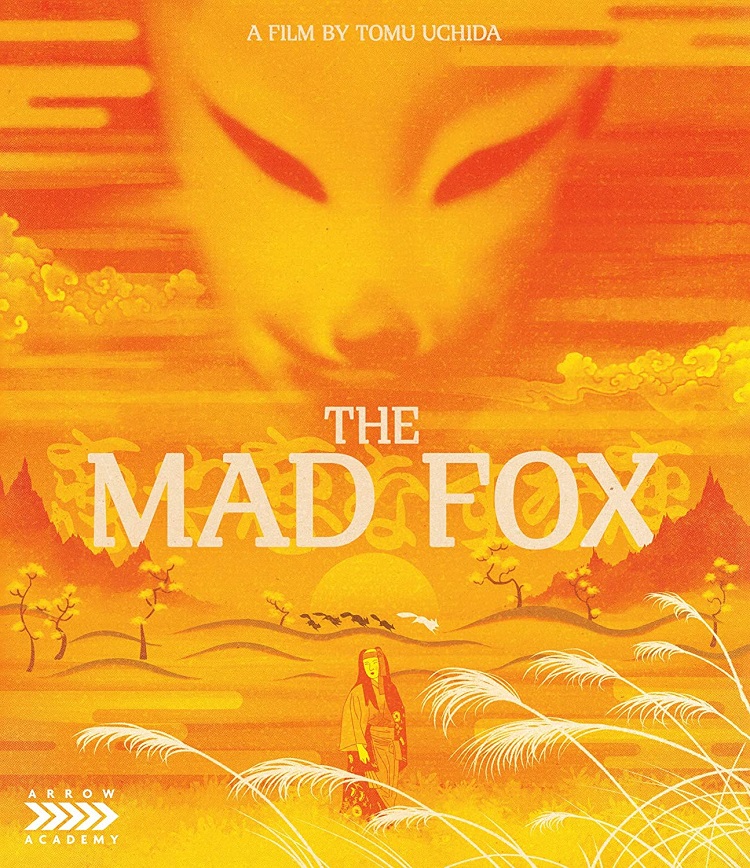

The Mad Fox has been released by Arrow Academy on Blu-ray. Included on the disc is an audio commentary by Japanese cinema expert Jasper Sharp. The included booklet contains an essay on Uchida by Hayley Scanlon and an essay on the film by Ronal Cavaye.