As anyone who ever found themselves making that awkward transition from one school to another during their years spent in educational institutions can attest to, it’s not at all easy to be the new guy. The pressure gets turned up to an unbearable temperature as people around you begin to unjustly judge you right off the bat – just because you don’t conform with their expectations of how a total stranger should look. What, then, might occur when you’re not even the guy that was meant to be there? Supposing you’re the new guy’s surrogate – only there because the man intended for the job was unavailable – and you are simply just filling in for a spell?

Yeah, I really can’t imagine what that might be like, either. But Timothy Dalton sure can. In 1968, the Welsh-born actor – who was only in his twenties at the time – had been seriously considered as the replacement for Sean Connery, but he himself felt the part required an older actor, and figured walking in Connery’s shoes wouldn’t be a wise move (I’m waiting for confirmation from George Lazenby on that). A decade later, Dalton was approached once more – this time intended to replace Roger Moore – but the performer felt it was better to decline since the kind of films being made at the time were like, well, Moonraker.

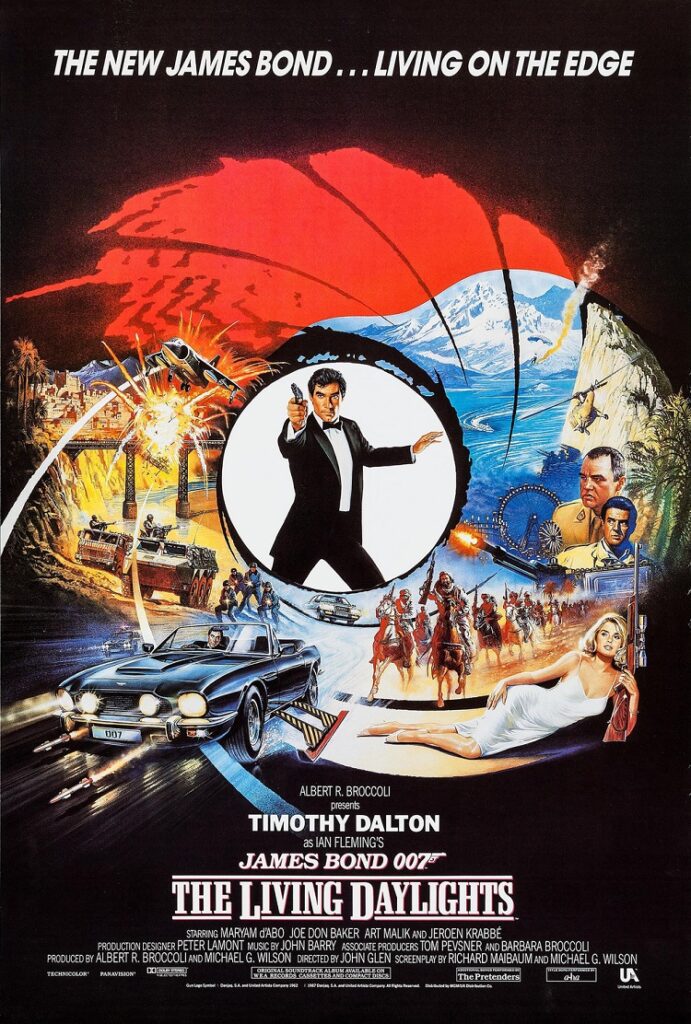

Nearly another decade down the road, Dalton finally conceded and agreed to become the new James Bond. Alas, he was only really asked to do so this time ’round since the man 007 producers wanted onboard – a fellow by the name of Pierce Brosnan – was under contractual obligations to a television series called Remington Steele. The story was a hundred times better than Moonraker. The era was that of the end of the Cold War. The star was rarin’ to go. But was the public ready for the man who waited nearly 20 years to take the lead?

Well, yes and no.

Say what you will about Casino Royale (2006) and maybe one or two of the other 007 movies, but 1987’s The Living Daylights – the fifteenth (official) James Bond film – is one of the few films of the entire franchise to adapt one of Ian Fleming’s stories in a slightly faithful manner (well, as faithful as this series can be!). And, since the source material (also entitled The Living Daylights) was nothing more than a short story, the writers of the film were able to squeeze a modernized take on the tiny tale in a post-credit sequence – allowing plenty of room for liberties to be taken with the proceeding tale from thereon in.

For the proverbial pre-credit sequence, however, we are introduced to Dalton’s Bond during a routine training mission at Gibraltar; a mission that goes (un)expectedly awry when an assassin shows up and starts to pick off MI6 agents left and right. Fortunately, our new guy is much younger than his filmic predecessor, and ready for action. He delivers, of course, in an exciting scene that finds a runaway jeep barreling down the famous promontory with Bond hanging on for dear life. From there, we get some exceptionally ’80s credits (and the pretty girls with it) with a theme song performed by popular Norwegian group A-ha (carrying on with the pop song trend begat in the previous film, A View to a Kill).

As for The Living Daylight‘s main story itself, we open with Bond deliberately sparing the life of a beautiful female cellist in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia, who has, for some reason, been assigned to eliminate a defecting general, Georgi Koskov (Jeroen Krabbé), who is taken to England for debriefing by M (Robert Brown, safely adhered in his new role, having replaced the late Bernard Lee several films earlier) and Minister of Defence Gray (Geoffrey Keen). During the debriefing, Koskov announces a major bombshell: new KGB head General Pushkin (John Rhys-Davies) has initiated the old policy of Smert Spionam (Death to Spies) – hence, the killer at Gibraltar.

Obtaining orders to assassinate Pushkin, Bond first returns to Bratislava to track down the faux sniper/real cellist from the beginning portion of the film in order to fill in a few gaps in his book of questions. He soon learns that the cellist – Kara (Maryam d’Abo) – is actually Koskov’s girlfriend, and that the whole assassination thing was just a big phony ploy. He also (eventually) discovers that Koskov is actually attempting to have Pushkin killed so he may place his weasely ass in power – control he is planning on gaining with the aid of an American arms dealer, Brad Whittaker (the great Joe Don Baker, who would appear in two more Bond movies – GoldenEye and Tomorrow Never Dies – as CIA agent Jack Wade).

The adventure takes us from Vienna to Tangier, and onto Afghanistan – wherein James helps out the Mujahideen in their struggle against the Soviets. Opium, diamonds, arms dealers, the Cold War, the return of the Aston Martin (V8 Vantage) we all know and love, those god-awful Members Only-style jackets: they all come into play here, in a superior Bond outing that co-stars Art Malik, Andreas Wisniewski, and Thomas Wheatley. Old school regular Desmond Llewelyn returns as Q, while a few cast changes bring us newcomers Caroline Bliss and John Terry: who make for the least-memorable Miss Moneypenny and Felix Leiter (respectively) in the entire series.

Additional changes in the music department are quite noticeable as well. Aside from A-ha’s contribution to the score, Chrissie Hynde and The Pretenders donate two songs to the film’s soundtrack: “Where Has Everybody Gone” and “If There Was a Man” (a song I secretly wait for someone to absolutely nail at karaoke just to win me over) – both of which tend to pop up in the movie throughout, with the latter track being played over the end credits (another change for the series). Longtime 007 composer John Barry provides us with his final score for the series, mixing classic musical arrangement with contemporary rock – a quite unheard-of method at the time (which has become the norm in this day and age).

The main objective of The Living Daylights is the tone itself. After Roger Moore’s oft-goofy outings, and with the swingin’ and funky sights and sounds of the ’60s and ’70s moved back to the furthest repressed reaches of the general public’s mind, it was time to focus on Bond himself: and that’s where Dalton hits one home in my eyes. He presents us with a solemn, rather humorless, and disgruntled Bond – a very human incarnation that seems perfectly content with being sacked by M any day of the week, and whose disillusionment would only grow worse in his second and final film as the iconic character, License to Kill in 1989.

Just like Frankie, Elvis, and Sid, Timothy Dalton did it his way, including several of his own stunts: something his predecessor certainly didn’t do.

A box-office hit, The Living Daylights managed to win over many filmgoers and critics alike when it was first released in 1987 – going as far as to beat the sales of The Lost Boys during opening weekend.

After the disappointing reception of License to Kill, however, Timothy Dalton was doomed to soon be forgotten by his peers and fans alike (the six-year gap between License to Kill and GoldenEye, along with the complete change of the world in general – i.e. the end of the Cold War, the introduction of making all things politically correct-like – didn’t help much, either), eventually earning the completely unfair title of “Worst Bond ever” by people who probably never picked up an Ian Fleming book in their entire life, and who would also possibly praise Die Another Day as the best film in the entire series (sigh).

Oh, well. You had my support back then, Tim, and you shall until the day that I die. I hope that means something to somebody somewhere. In the meantime, until a better film comes along, The Living Daylights earns a prestigious spot in my memory as the Second Greatest Bond Film Ever.

My first is Thunderball, just in case you’re wondering.

Operation: BOND will return with License to Kill.