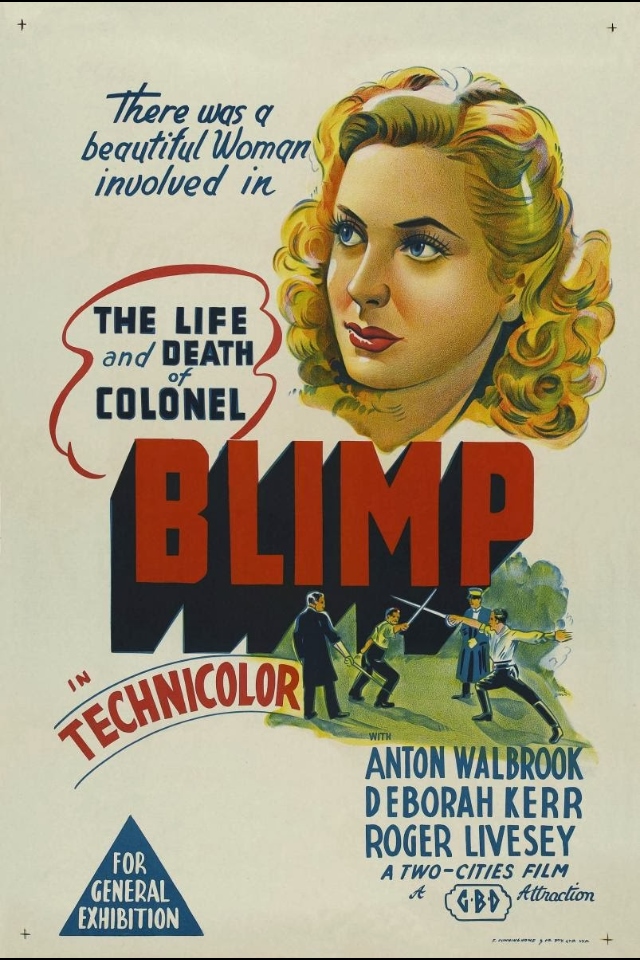

Martin Scorsese’s Hugo arrives in theaters on Wednesday in eye-popping 3-D. Before (and after) then, the Academy Award-winning director would like New Yorkers to see an equally groundbreaking film, made more than 60 years ago using state of the art visual techniques.

”I always like to look at it a few times a year,” Scorsese said of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 1943 classic The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, before a sold out screening at Film Forum on Friday. “It grows more enduring and more moving (each time) I watch it.”

Now, thanks to an effort spearheaded by Scorsese’s Film Foundation, audiences can see this epic story of fictional British General Clive Wynne-Candy like they have never seen it before: restored to the stunning vibrancy of its original Three-strip Technicolor.

”Three-strip Technicolor is a process with three color records: yellow, magenta and cyan,” Film Foundation executive director Margaret Boddie told the Film Forum audience. “The three black and white records of different colors are printed with dye, one on top of the other, to make the finished print, like old lithography. And that’s why the color in Technicolor films is so exquisite and so pronounced.”

But the three-strip production process meant three strips of negative and, according to Boddie, “three times the restoration.” Each of the three negatives was scanned at a resolution of 4k (4,000 pixels of horizontal resolution) and digitally cleaned up and color corrected, frame by frame, before they were merged into the final composited image, a 35mm print of which is being screened at Film Forum until December 1.

”There was mold that grew on the nitrate, because the negative had been put away wet,” Boddie said. “There were other challenges that had to be dealt with: aging, dirt and scratch removal, image stabilization and color breathing. These things take you out of the experience. Instead of watching the film, you’re watching gunk dance around the frame.”

Good news: the gunk is gone. And the original duration of 163 minutes has also been restored.

”(Powell and Pressburger) were forced to make cuts upon its release outside of England,” Boddie said. “In the U.S. it was truncated to 90 minutes.”

Scorsese told the Film Forum audience that he first saw the film in its shortened form on black and white television in the late 1950s.

”I never really got to see the complete version that you’re going to see tonight,” he added.

That all changed in 1983, when The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp was reconstituted to its original length by the British Film Institute. But the original negatives were not used in that restoration.

”Most of the color versions I saw were pretty much faded purple or magenta,” Scorsese lamented. “But, at least we got to see some sort of semblance of continuity in the film.”

Now, thanks to three years of work by the Film Foundation and Scorsese’s longtime editor (and Michael Powell’s widow) Thelma Scoonmaker, audiences can finally see Powell and Pressburger’s first color film in its original glory.

”What I really found fascinating about the film, even in its 90-minute version, was the way it was structured for storytelling,” Scorsese said. “The big dramatic moments – characters dying off, the winning and losing of wars – all happen off-stage. What’s left is the warmth, the friendship, the humorous moments, love, tenderness, sadness.”

The 69-year-old director added that Colonel Blimp’s narrative structure inspired some of the creative decisions he made on Raging Bull, which he was preparing to direct when he first met Powell and Pressburger in the late 1970s.

”There’s only about nine minutes of fight scenes in the final picture,” Scorsese said of his 1980 film starring Robert DeNiro as boxer Jake LaMotta. “You know he (Jake) wins, so why show the fight? (Colonel Blimp) did affect Raging Bull in a very interesting way.”

Another similarity: like a number of Scorsese’s films, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp was plagued by controversy during and after production. The character of Theo (played by Anton Walbrook, who would go on to achieve cinematic immortality as impresario Boris Lermontov in Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes) is a German soldier who was portrayed as sympathetic, hardly a welcome storytelling choice for a British film in 1943.

And the source material – David Low’s satirical comic strip about the buffoonish Blimp – was considered objectionable by Winston Churchill, who reportedly considered the film to be a parody of his wartime leadership. The prime minister refused to offer military cooperation to the production and issued a memo suggesting production be halted.

”The Army was against the picture being made and being exported and they really whipped up Churchill against the film,” Scorsese said. “The Minister of Information said (to Powell), ‘Please don’t make this film, or the old man’s going to get upset.’”

According to Scorsese, Powell asked the Minister if he was expressly forbidding them from proceeding with the production.

”Oh no, I would never say that. This is a democracy!” the Minister of Information replied. “But please don’t make this film or you’ll never get a ‘K.’”

The K was apparently a reference to knighthood, which neither Pressburger nor Powell were awarded with before their deaths in 1988 and 1990, respectively.

”They never got knighthood,” Scorsese said, standing at the podium in front of Film Forum’s big screen. “But they did get this picture. And finally, we all do too.”