Based on Cornell Woolrich’s dark novel, Black Alibi, The Leopard Man was the first property Val Lewton wanted to develop when he became the head of a B-film unit at RKO in 1942. The studio, stinging from very public, very expensive commercial fizzling of wunderkind’s Orson Welles’ Magnificent Ambersons, wanted to pump out cheap horror pictures in the vein of Universal’s famous monster movies. Val Lewton, a protégé of David O. Selznick who acted as, among other duties, an uncredited writer for some scenes of Gone With the Wind, was a literate and intelligent man who understood that without money for elaborate sets and frightening costumes, he would need to use psychology and the power of suggestion to make effective low-budget horror movies that weren’t embarrassments.

The first of these films, Cat People, was based on an original story by Lewton and was the box-office success RKO was looking for, proving Lewton’s formula could be successful. Ultimately, nine horror films came from the partnership including The Leopard Man. Despite being based on a successful novel and featuring the direction of Jacques Tourneur, who had helmed The Cat People, reception for The Leopard Man was unenthusiastic. Even Lewton and Tourneur eventually looked back on the film as something of a misfire.

Set in a small town in New Mexico, Kiki and Clo-Clo are rival nightclub singers (and not, as their names might suggest, some weird circus act). To get an edge of the more vivacious Clo-Clo, Kiki’s business manager Jerry rents a local attraction for Kiki to be seen with: a black leopard. She’s supposed to show Clo-Clo up in the middle of her castanet-playing act, but instead the castanets frighten the big cat and it runs out of the club, mauling the hand of a waiter on the way out.

Immediately, there’s a hunt put out for the animal, but to no avail. That very night a young girl is savaged and killed in the night. This death sequence is a masterpiece of subtle terror: the frightened girl has been sent out into the town to fetch corn meal, her mother angrily dismissing her fears of running into the leopard. The girl has to cross through tunnels and over desert to get to the grocery on the far side of town. It’s a long, slow build to her finally spotting the leopard just outside her home. In an oft-stolen bit of off-screen violence, her death is heard from inside her mother’s house, as the girl pounds on the door, begging to be let in. She screams while her mother struggles with the bolt, then goes silent. Blood spills in from the crack underneath the door.

The entire town is in a panic, as the leopard continues to elude capture, and two more women are found dead and mauled. Jerry, while putting on a tough facade, understandably feels responsible for the mayhem, but as he follows the police to the scenes of the crime he begins to grow skeptical that the deaths were the work of an animal. Circumstances in the deaths don’t seem to match with a frightened animal striking from either panic or for food. To him, these deaths look like murders.

The Leopard Man is the horror movie as whodunit. There’s a small crowd of suspects, and a lot of local character. One thing that is distinctive about the Lewton movies is the specificity of their setting. Everything in the film was shot on a sound stage except for some brief exteriors which were done by a second unit consisting of a single person with a camera, but it has the distinct feel of a Southwestern border-town, complete with a cast of quirky locals: the man who owns the leopard, the professor interested in local Indian folk-lore, the fortune teller always finding the death card in her readings. There’s none of the generic villagers and shop-owners that would populate a less well-considered film.

What it doesn’t have is a tight focus on its main characters. The Leopard Man leaves Kiki and Jerry, our ostensible leads, for large sequences of the film, especially for the three murder set pieces. Some have seen this as a flaw of the film, but while watching it I found my sympathy as an audience member (and so my interest in the film) easily transferring to the different characters. It put me in mind of a movie that wouldn’t be made for another 17 years, Psycho, where Hitchcock masterfully moves the audience’s emotional connection from Vera Miles to Norman Bates. There isn’t that radical a shift in The Leopard Man, but I found it a really engaging way to make a film.

It’s a brisk film, too, weighing in at only 66 minutes long without an ounce of flab on it. And even in that short running time, it manages to craft memorable and unique sequences, culminating in a deeply visually striking climax. At an annual memorial for a massacre of Indians by Conquistadors, the villagers don black masks and robes and march up a hill. In the middle of the procession, Jerry engages in a foot chase with a murder suspect, and it is an incredibly eerie, strange-looking sequence unique in ’40s Hollywood.

When I first watched The Leopard Man years ago when I was first exploring the films Val Lewton produced, I thought it had some neat visuals but was lower tier Lewton and Tourneur. This new viewing, on the beautifully restored Blu-ray, has changed my mind. It’s a minor masterpiece of suspense filmmaking, incredibly economical in creating its frightening sequences, and sensitive enough to create dimensions for even the smallest or most initially unlikable characters. This is top-tier ’40s American horror movie-making.

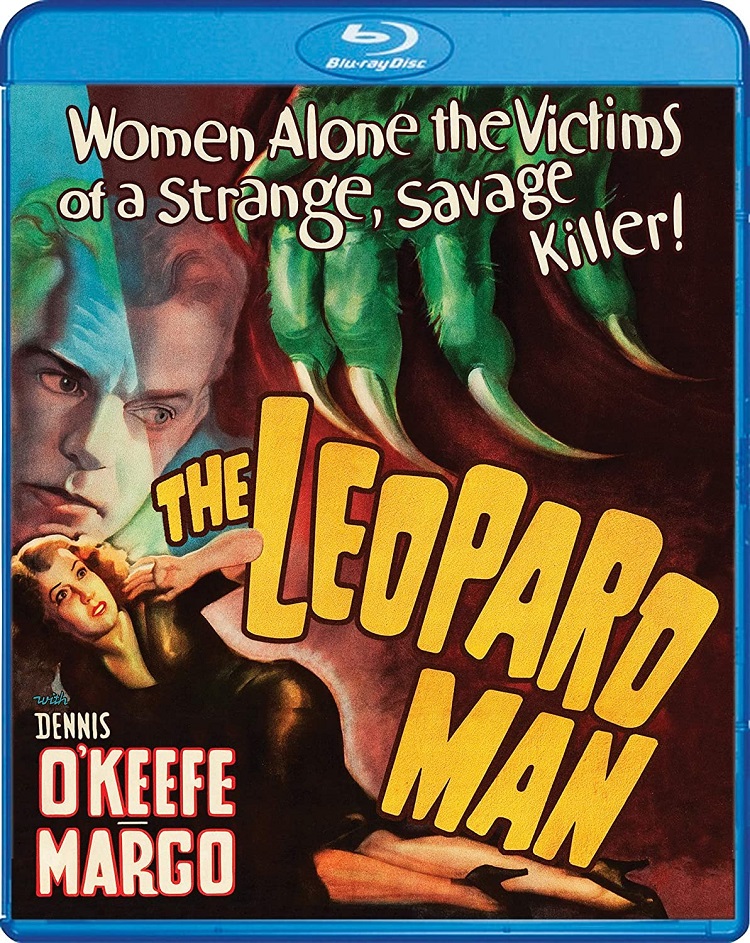

The Leopard Man has been released on Blu-ray by Scream Factory. Besides a trailer and some stills, the extras on the disc include two commentary tracks. One is by director William Friedkin, and is a hold-over from the previous DVD release. The second, new for this release, is by film historian Constantine Nasr which contains a wealth of historical information about Lewton, and the production of this film in particular.