Except maybe Citizen Kane, everything Orson Welles directed has a kind of asterisk by its name. However good the movie is, it was never what it was meant to be. Studio interference, lack of money, backstabbing by collaborators, all kept the auteur from his true vision. After a while, one might start to wonder if the man himself is the problem, not literally everybody else he works with.

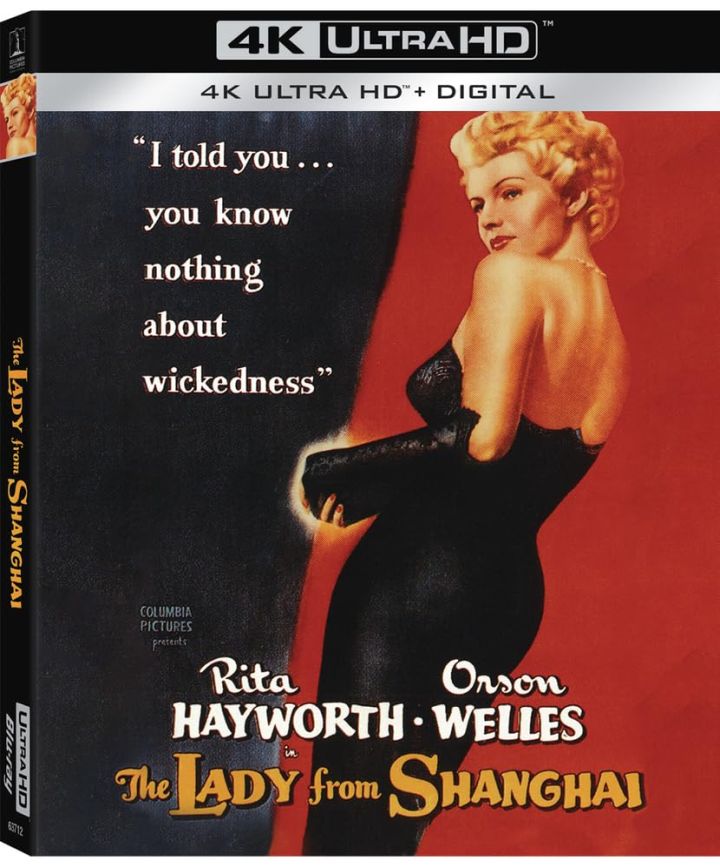

Buy The Lady from Shanghai 4K UHDThe Lady from Shanghai (1947) was Welles’ fourth fiction film, and another that was plagued with production delays. It was released in a cut that was taken from the director’s hands. And like all his wounded-bird productions, it has elements of genius that seem somewhat incompletely formed.

It’s the director’s firmest foray into film noir. I don’t consider The Stranger, its predecessor, to be a proper film noir since it is not about the fall of its protagonist. The Lady From Shanghai definitely is. From the beginning narration, Michael O’Hara (Welles) lets us know he’s in for a big collapse. And it’s his own fault.

He meet-cutes Elsa Bannister (Rita Hayworth, Welles’ wife at the time) when she’s on a carriage ride, and he’s on foot. Minutes later, he rescues her from some ruffians, then steals the carriage to take her home. This first sequence of the movie is typical of the film’s narrative structure, which doesn’t concern itself too much with plausibility. The film makes sense, taken as a whole. But each sequence has a dreamlike quality that makes the whole thing like a recounting of a nightmare.

For instance, after Michael rescues Elsa, he takes her to the garage where her car is waiting and meets a few shadowy characters there. Later, when he’s coerced (by her husband, no less) to be a bosun on a cruise ship, those same shadowy characters end up on the ship. There are plausible reasons for their presence, but it has a rather nightmarish quality, where they show up again and again before the audience knows why.

Welles employs the strategy constantly, contrasting a natural realism with obvious artifice. Scenes obviously shot on location are intercut with shots that are just as obviously processed. There’s an entire sequence in an aquarium where the displays are sometimes real, and then clearly rear projections. They don’t make moray eels the size we see them in the movie.

It fits the elements of this ramshackle, strange story. O’Hara is hired onto Elsa’s cruise by her husband even though she’s clearly taken with him. The husband knows it, and mentally tortures both over it. After half an hour of this bizarre not quite love triangle, Bannister’s law partner, George, comes to O’Hara with a strange proposition: he wants O’Hara to commit a murder. More specifically, George wants O’Hara to kill himself – George, not O’Hara.

But maybe, not really. There are twists and turns in the plot. But the plot is only part of the point of a Welles movie – the camerawork and the lighting and the entire production is his deeper concern. Famously, about 20 minutes of the climax of the film was cut out from the final release. The ending takes place in a carnival, and while what we have is pretty extreme, what Welles planned was much more elaborate.

Whether that would be better than what we have or too much to bear is an unknowable question. That footage is lost, likely never to be found. What we do have is a beautifully helmed film that has a bunch of rough, odd edges that make it interesting. Almost all of the main characters seem to hate each other, have plots against each other, and place Michael O’Hara at the center of their machinations for seemingly no reason.

Their lives are a game, and one that isn’t that plausible. It’s hard to feel that Welles took this movie too seriously. He plays Michael O’Hara with a thick Irish brogue which feels more committed than authentic. His wife, Rita Hayworth, was known for her thick brunette locks. Here, she’s a short-haired blonde. Her husband can’t be subtly impotent, he must walk with two canes, held against his legs like crutches. The third act takes place mostly in a courtroom where everyone, judge and lawyers included, treat it like a circus.

The movie is always on the level of near surreality, and the justly famous final sequence in the mirror funhouse takes it to its logical conclusion. It’s a wild ride. But it also feels a bit like a test. For general audiences, this movie might be too arch. Too… “cinematic.” Especially for its time (1947), it’s pretty bloody weird, and relentlessly so. It feels like it’s challenging the audience, constantly to keep up… and then at the end doesn’t have much of a reward.

Maybe that’s the studio interference. Maybe it’s the pretense of the filmmaker. The Lady from Shanghai is an exercise in expert style, and decent storytelling. This 4K UHD release highlights the excellence of Hollywood filmmaking at the time, because the image is consistently beautiful. When they are shot together, Elsa always has some sparkling white features, and O’Hara is dark, sometimes completely black. It’s a beautiful film to look at, and this 4K representation would be hard to improve upon.

The movie itself… has interesting elements. It’s fast paced and has beautiful locations and a decent if convoluted story. From what little I can gather of information about the lost elements, they would have been more interesting than good. The conclusion of the film is already at the extreme end of logical expression. More would have thrown the film into pure surrealism. But this is a beautiful edition of Welles’ flawed, and damaged vision.

The Lady from Shanghai has been released on 4K UHD by Sony Pictures Home Entertainment. This release does not include a Blu-ray disc, but it does have a digital code. Extras include a commentary by Peter Bogdanovich, a short video feature with the same (21 min), and a trailer.