Written by S. Edward Sousa

The Grand Budapest Hotel has all the trademarks of a Wes Anderson film: a vast cast of talented actors used in either requisite amusing cameos, like Owen Wilson as Monsieur Chuck, or in critical tertiary roles, like Willem Dafoe as the Germanic deviant JG Jopling. There is the obligatory young romance rendered here by teenage lobby boy Zero Moustafa and teenage baker Agatha, played with earnest by Tony Revolori and Saoirse Ronan, respectively. Their relationship, as with all of Anderson’s adolescent couplings, mixes a bit of naivety with world-weariness; they are mature enough to believe their love will save them from becoming grown-ups. And there is the sentimental man-child trapped by past loves and former glories. F. Murray Abraham plays the elder melancholy Zero Moustafa, recounting for us a fond and exciting tale of a distant time in his life. A time he hopes to recapture, passing through The Grand Budapest Hotel in search of a joy he once knew.

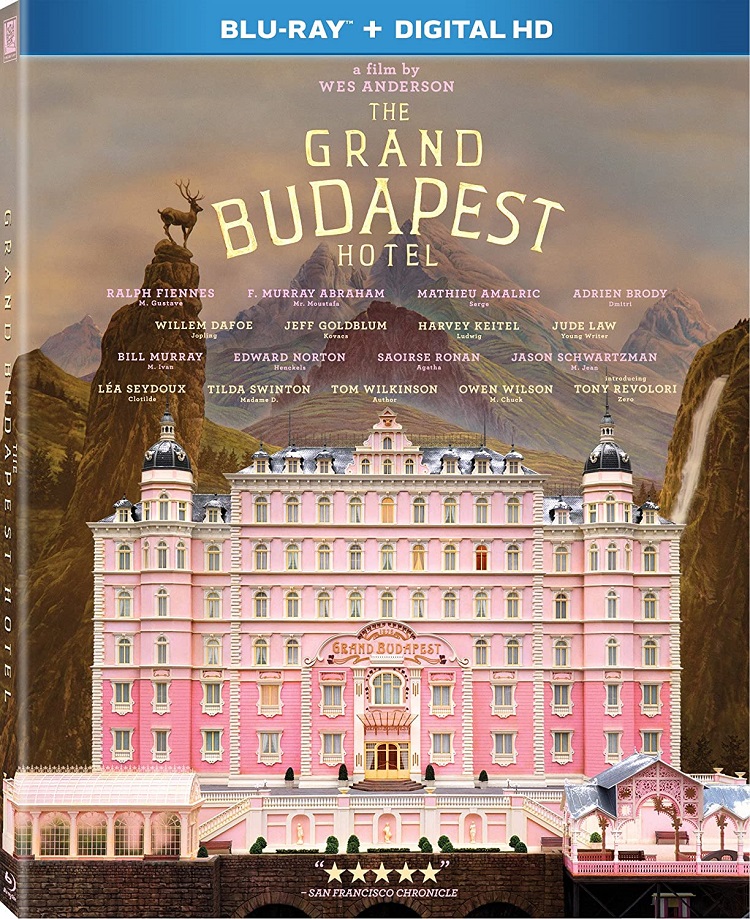

This last bit of nostalgia lies at the heart of The Grand Budapest Hotel, a visual feast of a caper film. A chance encounter at The Grand Budapest, located in the fictionalized Eastern European country of Zubrowka, brings together the aging and downhearted Zero Moustafa and “The Author,” played by Jude Law. Zero recounts for “The Author” the most meaningful years of his life, his time under the tutelage of premiere hotel concierge Monsieur Gustave H, a queer and charming Ralph Fiennes. Gustave’s predilection is for wealthy elder women, embodied with brittle humor by Tilda Swinton as Madame D. Her passing early in the film leaves an immense estate to be devoured by everyone from her children to the most outlying of relatives.

The twist comes when Madame D bequeaths Boy with Apple, a rare painting by Johannes Van Hoytl the Younger, to Gustave. Her son Dmitri, a vicious and comedic Adrien Brody, pursues Gustave for the murder of his mother. The next hour is spent weaving through multi-colored site gags and jittery, Fritz Lang-style camera work as Gustave goes on the run with the aide of Zero and his love Agatha. Jailbreaks, murder, and a secret society of hotel concierges are all handled with the brilliant colors and quick wit Anderson is known for. Yet at the heart of the film is our narrator Zero, whose aging sorrow becomes the film’s undercurrent as he grapples with the dissolution of time and memories.

Anderson dedicates the film to Austrian author Stefan Zweig, an early 20th Century fictionist known for humorous, surface-level observations. Like Zweig, forced from his native land after the rise of Hitler, Gustave is forced from Zubrowka by The Zig Zags, a re-imagined SS, on the verge of a vague World War. All of Anderson’s worlds are illusory; fixed in a thoroughly modern past, a retro present with the convenience of today and the allure of the vintage, often paralleling the stunted nature of his adult characters. And like critics said of Zweig, Anderson, as of late at least, has become a superficial adventurer. Beginning with Fantastic Mr. Fox and continuing through Moonrise Kingdom and The Grand Budapest, Anderson’s forged a trilogy of near soulless films; amusing, yet contrived narratives full of unsympathetic and emotionless characters. The Grand Budapest, the most vapid and eye-catching of all his works, exposes Anderson’s weakness—once brimming with poignancy and emotional resonance, his films have given way to plot-driven, visual escapades.

I fell for Anderson within the first few frames of Rushmore; it felt written for me, though perhaps being in a theatre with one other person solidified my connection. I remained unwavering through The Darjeeling Limited, his most spiritual and arguably privileged work, but after that I take issue. He lost the ability to create depth. Sure, the emotional tone of his work has always been adolescent, from Bottle Rocket on he managed to cast actors and create moments of emotional nuance. These scenes have been subtle, like Herman Blume meeting Max Fischer’s father Bert for the first time in Rushmore, and they have been heavy, like Peter Whitman’s inability to save a drowning boy in The Darjeeling Limited.

Yet there is a glaring absence of these moments in Fox, Moonrise, and Grand Budapest. Anderson seems to be chasing an awareness of himself as a quirky filmmaker rather than what once drove him—confronting arrested development with the sands of time. His fixation on aesthetics replaced sympathetic characters with optical delights; while watching The Grand Budapest is wondrous, relating to it is impossible. Anderson paints from a distinct pallet—his penchant for vibrant, meticulous costuming and set design evolved from rough around the edges in Rushmore and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou to the crisp detailed landscapes of these later films—but he lost sight of how characters are to exist within these candy-coated worlds.

In fact the character of these worlds matters more than the characters in these worlds. The Grand Budapest Hotel is the most glaring example. Seen here on Blu-ray—a format his vision benefits from—the detail of Zubrowka is animated in delightful ways; the scale model hotel, the animated costuming, the life breathed into often drearily depicted Eastern European towns. The tricks and trappings of the film are magnified in a series of bonus features on the disc—an expose on the Society of Crossed Keys, a behind-the-scenes documentary, and a chance to watch Bill Murray eat sausage, far more fascinating than imaginable. The plot is exciting, the characters are fun, but I have no empathy for any of them, a drastic change from his earlier works. Anderson is easily one of our best filmmakers, even his worst work is worth the time, cash, and conversation, but he appears to be at a crossroads.

A friend of mine said watching an Anderson film is like watching a kid play with a diorama alone in his bedroom. The emotions are flat, near black and white, like a child’s, and the more time he spends alone in the bedroom the more specific and alienating the diorama gets. I tend to agree, Anderson straddles the line between childhood and adulthood, a territory he once explored, but now takes for granted. Perhaps success afforded him this disposition, but the thing is I straddled this line long enough on my own and I have enough Peanuts comic strips already, so he should just pick a side and go for it.