Classic gangster movies followed a specific arc, probably best codified in the original Scarface (1932) – the audience follows the gangster from his lowly beginnings to the giddy heights of crime-bossery, and then watches as the gangster, who is a bad guy, falls from these heights. The thrill of vicarious transgression combined with the self-satisfaction of righteous condemnation. In the move away from the studio system and strict controls over content, artistic freedom, and fashion of the time shifted the paradigm toward moral ambiguity, the gangster became less of a tragic figure, and more aspirational: the man who has transcended the bonds of conventional morality – he might still be bad, but he gets things done.

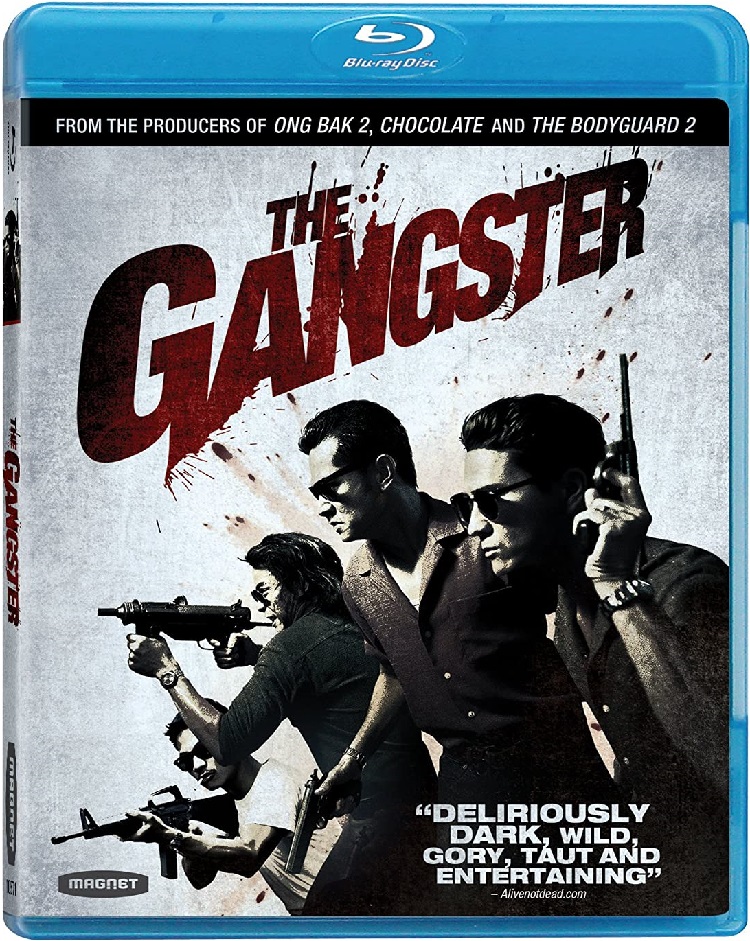

Goodfellas, Scorsese’s ’90s masterpiece, is the prime example of this: Henry Hill is observed, not judged, and in the end when he joins the witness protection program to save his life, the movie hints that the real tragedy is not what he did as a gangster, but that he doesn’t get to do it anymore. The Gangster, a Thai film from 2012, borrows heavily from Goodfellas mode of storytelling and tone, eschewing plot for the most part to show the daily lives of gangsters in the ’60s and early ’70s.

The film is primarily the story of Jod, a taciturn, handsome man with a doting mother and sister. He’s a gangster because he wants to keep them safe, but in the world he inhabits, there doesn’t seem to be much choice. In the claustrophobically narrow streets of Bangkok, the only alternative to being beaten by random street thugs is to be the thug doing the beatings. These fights and their retaliations make up the bulk of the action of the first hour of the film, including a visceral, thrilling early sequence with Jod having a knife fight with one of the street bosses.

The fight starts with a calm, friendly conversation between the two. The boss knows Jod is going to run with another gang, and he feels it’s an affront. They share a coke, then tie their wrists together, and slash at each other with knives. While the relationships between the gangsters are always contentious, there’s at least the pretext of a code, a way of living.

As the years go by, that code deteriorates. Some gangsters, particularly Pu the Molotov Cocktail, beat and rape the women of his enemies. In one of the most graphically shocking scenes of violence in the film, he smacks a girl who refuses his advance in the face with a bag he’d forgotten contained an explosive, blowing most of her face off.

Eventually, knife fights give way to guns, and the police crackdown on gangs. Jod goes to jail for a few years, comes back, and then resumes his gang life, because there’s nothing else to do. Two young gangsters serve as his underling, who grew up together in the back of a movie theater and admired Jod about as much as they did Elvis, whose pompadour and dance moves they appropriate. The film is filled with fun period details. The girls dress in fashions cribbed from the American movies the theater shows. Apparently showing an English-language print, the projectionist would bark out the lines in Thai to the audience from his booth, pitching his voice higher for the female lines.

Interspersed throughout the film are documentary interviews with old Thais, talking about life when the gangs ran wild. They discuss Pu and Jod as if they were real people (though a cursory internet search does not reveal whether the film is based on true stories, or if these interviews and the people in them are fictional.) What’s more important are the level of verisimilitude they offer, and how they keep the film feeling grounded, and serious, and give it a structure that the mostly plotless series of escalating gang fights lacks.

Sometimes the period details falter. During the crackdown, there’s a sequence that is made to look like it was shot on Super 8mm film, and it looks exactly like an editor using the Super8mm filter on his visual effects software. The rock ‘n’ roll music in the early ’60s sounds like library tracks and ginned-up versions of fake rock tunes. It’s not surprise a Thai movie production could not afford the license to real Elvis songs during the Elvis movie, but it’s a rather jarring disconnect.

Jod is the heart of the film. His soulful look and apparent regret somehow keeps his character sympathetic, even after he accidentally shoots an innocent bystander in the neck. He’s visited later by that bystander’s ghost, as the second half of the films pulls away from the documentary sensibility and becomes more and more a standard crime story.

And that’s The Gangster‘s main failing – in order to end the story with a bang, it becomes more about people shooting each other, double crosses and police informants and revenge. None of these elements are bad: the action is taut, and keeps its feet mostly in the real world. But these elements are stock, while everything that came before felt fresher, more emotionally real. The first half of the film is propelled forward despite the lack of growth in the characters – they are stunted individuals, with vague notions of “getting out” but no real ability to see the horizon. The Gangster is at its strongest when it follows the inevitable trajectory of go-nowhere kids. When it becomes more abut the shootings than the shooters, it loses its way. By no means a bad film, The Gangster falls short of being a great one.

The Blu-ray of The Gangster features a gorgeous transfer. The cinematography contrasts the natural beauty of Thailand, the tropical climate against the closed-in, sweat drenched claustrophobia of the city. This is rendered beautifully in the transfer.

The main extra on the disc is a short “Making of” which lasts eight minutes, consisting mainly of different actors and the director letting you know they like the movie they made. Good for them. There is also a “Behind the Scenes” featurette which lasts less than two minutes, and consists just of scenes of the movie being filmed – no background information, no context, no narration.