Written by Brandie Ashe

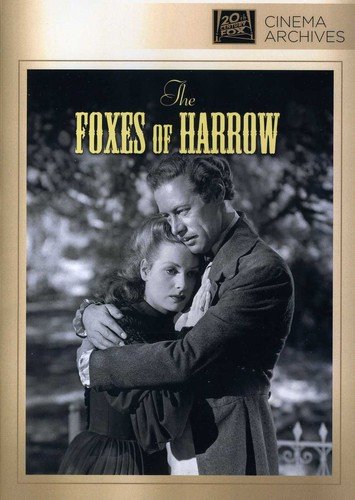

When it comes to antebellum costume pictures, the inarguable standard-bearers are Jezebel (1938) and Gone With the Wind (1939), both of which center around strong, independent women bucking the norms of an oppressive Southern society. These films are marked by gorgeous set pieces, brilliant staging, strong performances, and crisp, well-fashioned dialogue, all combined into singularly magnificent film experiences. The 1947 film The Foxes of Harrow (recently released via MOD DVD through Fox Cinema Archives) attempts to emulate this successful formula, albeit with a reversal in gender: this time around, the main character, Stephen Fox (Rex Harrison) is the illegitimate adopted son of Irish manor servants who travels to America to make his fortune gambling on Mississippi riverboats. He falls in love with a young Creole woman, Odalie D’Arceneaux (Maureen O’Hara), whose family is part of the upper crust of New Orleans society. Despite the less-than-savory aspects of his character, Odalie is intrigued by Stephen and eventually agrees to marry him, setting up house at Stephen’s plantation, Harrow. From the start, however, their life together is far from idyllic, marked by the violence, tragedy, and despair of an increasingly maudlin series of events, culminating in the loss of Stephen’s fortune and family.

In its attempts to mimic the epic grandeur of its predecessors—particularly GWTW, whose influence is undeniable here—The Foxes of Harrow falls epically short. Despite a comparatively lean running time of less than two hours, Harrow drags and drags to the point of tedium (I love Maureen O’Hara to death, but ye gods, was it difficult to make it through this entire film!). The story has the potential to be engaging, but something is missing. It could be that in the effort to excise material from the source novel by Frank Yerby (which itself owes a great deal to Margaret Mitchell’s literary masterpiece), the spirit of the story was lost, leaving behind only the dregs of a compelling narrative (I can only speculate here; I haven’t read the book).

According to the TCM article about the film, a great deal of the storyline was removed per the strictures of the Production Code, including much of the provocative racial material regarding the relationships—personal, monetary, sexual, or otherwise—between slaves and masters in the old South. Yerby, the first African-American author to be paid six figures for the right to adapt his work, focuses an equal amount of attention on the white characters and the black characters in his original novel, but the script whitewashes the story to the point that the slave characters are relegated to little more than supporting players (if that). Furthermore, in order to receive a Code certification, the character of Stephen’s mistress, Desiree, could not be portrayed as being of mixed race as she is in the novel; instead, she is drawn as wholly white (and wholly innocent). The resulting film reflects only a pale shadow of the searing social commentary it could have provided, had Darryl F. Zanuck and The Powers That Be at Fox been willing to push back at the demands of the Breen office.

A couple of years ago, I read Maureen O’Hara’s autobiography, ‘Tis Herself, in which she reflects upon her interactions with many of her co-stars over the years. Most are remembered quite fondly; Rex Harrison, however, is not. O’Hara writes that her experiences in making this film were horrible, and that Harrison was “rude, vulgar, and arrogant,” belching in her face during close-ups to irritate her. In her memoir, O’Hara even engages in some speculation about the true motives behind the suicide of Harrison’s lover, actress Carole Landis, soon after the filming of Harrow was complete (the scandal resulted in the cancellation of Harrison’s contract with Twentieth Century-Fox). Still, despite O’Hara’s obvious loathing for her co-star, there is no evidence of this dislike onscreen, and if Harrison and O’Hara’s chemistry is not exactly warm, it is due more to the stilted script than to any fault in performance from either actor.

As with other titles in the FCA MOD library, the disc comes with no special features or extras. But the transfer of the film is clean and clear—thankfully so, considering that one of the few strengths of this movie (along with the gorgeous costumes of Rene Hubert) lies in the lovely cinematography of Joseph LaShelle. The Foxes of Harrow is one of those titles I would generally only recommend to hardcore fans of either Harrison or O’Hara, but I have to admit, it’s also worth viewing just to see some of the beautifully-lit shots of O’Hara and company that populate the film.