Over the last few months, I’ve watched three World War I films (All Quiet on the Western Front, Paths of Glory, and this one), two of them pre-Code and all three staunchly anti-war. I find it interesting that so many World War I movies tend to depict war as horror rather than something brave and meaningful. It seems to me that most World War II movies tend to be geared towards the rah-rah than the cynical. It wasn’t until Vietnam that films seemed ready to embrace the dark side of the country-on-country battles again.

That’s some broad-stroke painting right there as there are lots of World War II movies that paint the dark underbelly of fighting Nazis, but I’d argue that in general, cinema leaned towards heroism during World War II and held their cynicism for the first one. Perhaps it is because Americans have lost sight of why we fought in World War I (did we ever know?) and it is hard to be cynical when talking about eradicating fascism and the Holocaust.

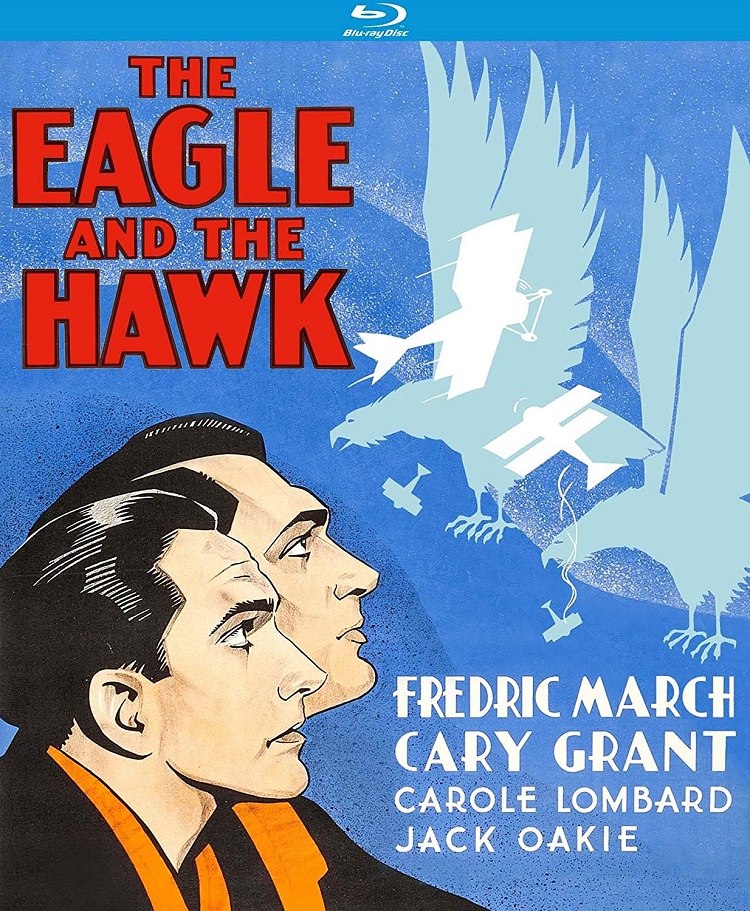

Whatever the case, I’ve seen some truly great films about World War I and its high cost, no only in lives but the psychological toll of those who survived. I can now add The Eagle and the Hawk (1933) to that list. It is a brutal, depressing tale of how being surrounded by death day after day can lead one into the darkest depressions. It has some nice dogfight action (though if you’ve seen any other movie from this period about aviation, you’ll not be seeing anything new here) and a wonderful central performance from Fredric March.

The opening credits introduce our characters – Jerry Young (March), Mike Richards (Jack Oakie), and Henry Crocker (Cary Grant) – full of life and vitality. Jerry’s playing polo, MIke is having a laugh in a cafe, and Henry is standing tall on the job. They all sign up to be fighter pilots, itching to go overseas and see some action. If nothing else, they think, it will be good for a laugh. Mike and Jerry get sent over first but Henry, whose introduction involves him landing a plane upside down, gets demoted to the back seat where he’ll be taking pictures and running the guns as an “Observer”.

The moment they land in France, Mike and Jerry are sent out on assignment. Both returned unscathed and excited to finally have seen war. Mike brags about the fact that he shot a plane down. Their merriment ends quickly though when they learn that Mike’s observer has been shot and killed. Suddenly, the thrill of adventure has soured into the hell of war.

A quick montage shows Mike losing more and more observers to German bullets. In a feat of acting, Frederic March uses his entire body to demonstrate his transformation from carefree young man to a depressed hulk. After that first observer dies, we see him writing a letter to that man’s family. His script is neat and full of fancy. Towards the end of the film, we see him fill out a report. His handwriting is plain and shaky. It is a subtle, but brilliant moment demonstrating his troubled psyche.

Henry Crocker shows up and is immediately disliked by everyone. He’s a little bit cocky but pragmatic too. On a flight with Jerry, we watch him gun down soldiers parachuting out of their destroyed balloon. When he’s chastised by his fellow soldiers – it’s like shooting a man in the back, one of them says – he bristles proclaiming this is war and one more dead enemy is one less guy to shoot at him. Henry and Jerry are forced to fly together for multiple missions. They hate each other but each of them is the best at what they do. They get medals from the French Army at one point. It is one of many for Henry who sees it as just another reminder of the men he’s killed, but a first for Jerry who elates at finally getting something to pin on his jacket.

At nearly the breaking point, Henry is given a couple of weeks off. He goes home hoping for a real respite but finds himself at dinner parties where everyone does nothing but talk of the war. A beautiful woman (Carole Lambert) is the only one to understand his despondency. She takes him to a park where they drink champagne and she listens to him complain about the war. Lambert gets top billing for the part, though she’s only in that one scene, and she’s worth every penny they paid her. It is a crucial scene, one in which someone finally understands his pain, and she plays the hell out of it.

Frederic March nails his role as well. His slow, psychic unraveling is unnerving, beautiful, and sad. Jack Oakie gets in all the jokes and he does them well, offering up some much needed comic relief. As much as it pains me to say it, Cary Grant is wrong for the part. He’d only been working in the movies for a little over a year when he made The Eagle and the Hawk (though admittedly, he was in nine movies prior to this one) so he’s still figuring out his style. But he still has that Cary Grant charm. He’s far too likable for a part that really needs some sour grit.

The airplane sequences are well done and director Stuart Walker provides some evocative imagery. It isn’t quite as unsettling as All Quiet on the Western Front, or as maddening as Paths of Glory, but The Eagle and the Hawk is a powerful, anti-war film about the horrors of war, especially World War I.

Extras on this Kino Lorber Studio Classics disk include an audio commentary from film historian Lee Gamblin and a series of trailers.