In the mid 1920s, composer Sigmund Romberg collaborated with the lyricists at large Oscar Hammerstein II, Otto Harbach, and Frank Mandel to create what would become a Broadway hit – The Desert Song. Inspired by the 1925 uprising of a group of Moroccan rebels, known as the Riffs, the musical play was later turned into a successful 1929 film rife with the kind of sexual innuendo and lewd humor (the kind you’d expect to find in a project that hailed from the decade we commonly refer to today as the Roaring Twenties) that was present in the original play. The title was also one of the few movies of the time to experiment with an early two-color Technicolor process – and thus, became the first film released by Warner Brothers in (partial) color.

Alas, once the Hayes Office began to enforce their strict moral code on movies in the ’30s, the original filmic version of The Desert Song was banned; the group of humorless censors apparently not impressed with the tale’s sex jokes or the fact that it sported an obviously gay comic relief character. Sadly, the 1929 film has not officially surfaced on home video to this day, but there are other versions available – each very different from the other. A 1932 Warner Bros. short (The Red Shadow) was followed by a 1939 remake from Germany – neither of which are truly relevant here (nor is any of it, I suppose), but serves as an interesting tidbit of information considering that the next feature-length American adaptation from 1943 would not only be set in 1939, but would be updated to include the menacing Nazis as a threat.

Now, with the exception of Mel Brooks or perhaps even Der Führer himself, a musical featuring Nazis is not something every person – even one who is actively involved in musical theater or world domination – envisions. In fact, it’s one of the last elements to be considered for a tale that is centered around singing and dancing. Fortunately (or unfortunately, depending on your own personal distorted tastes), said Nazi threat in the 1943 version of The Desert Song is a very miniscule underscore. It’s there, but never truly mentioned until the very end, when former enemies unite to destroy the greater evil before it gets its schickl-grubbing hands on a railroad (believe it or not, railroads once served a purpose apart from Monopoly).

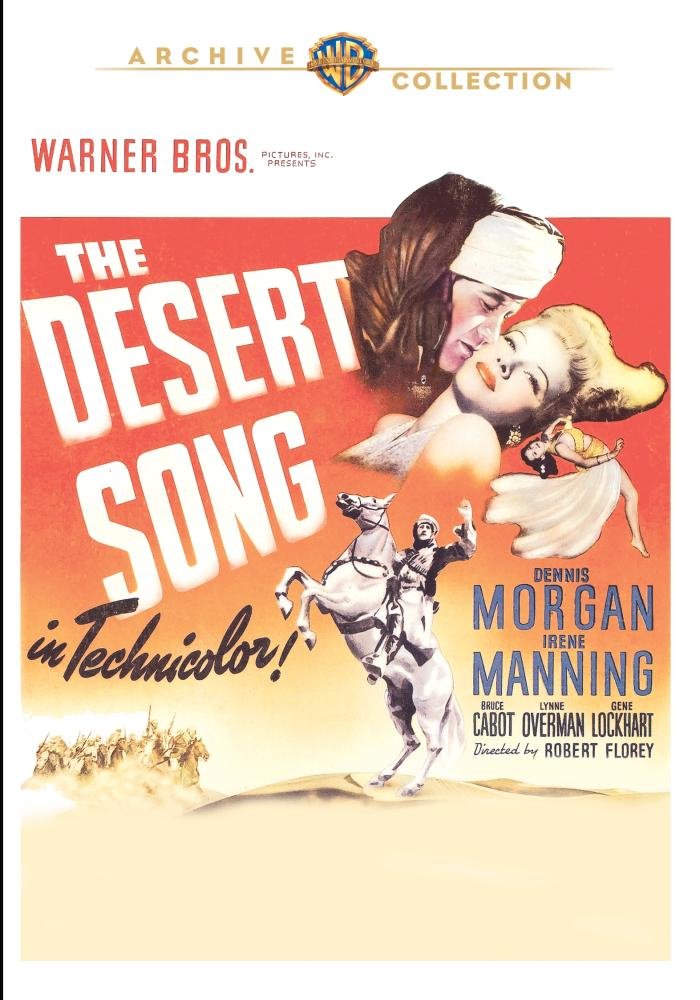

Originally set to be released in 1942 (the political situation abroad delayed the premiere, and the government itself thought the movie should wait) and filmed in full (still early) Technicolor, 1943’s The Desert Song finds a vastly different account of its source material; one that is (thankfully) short on musical numbers but rather sanitized according to the powers that be of the time. The hero’s alter-ego changed from The Red Shadow to El Khobar, the story here has jazz musician Dennis Morgan moonlighting as the Riffs key to freedom from an oppressive Caid Yousseff (Victor Francen), who is trying to gain the support of the French Army against the rebels while secretly conspiring with the Nazis the whole darn time.

Bruce Cabot is the oft-oblivious French colonel caught in the middle, who fancies French lounge singer Irene Manning more than anything. Imagine The Desert Song by way of Casablanca and you could probably hit it right on the head. The very gay comic relief character and his accompanying girlfriend (!) have since been changed to an older drunken reporter (Lynne Overman, doing what he does best) and the nosy French censor (a parable, perhaps?) whom the bored journalist has to come up with a new way to sneak his reports past. Gene Lockhart (June’ pappy), Nestor Paiva, Curt Bois also star in Robert Florey’s feature (which proved to be hit, even after being delayed a year); look close and you might spot Duncan Renaldo, Rick Vallin, and Gerald Mohr.

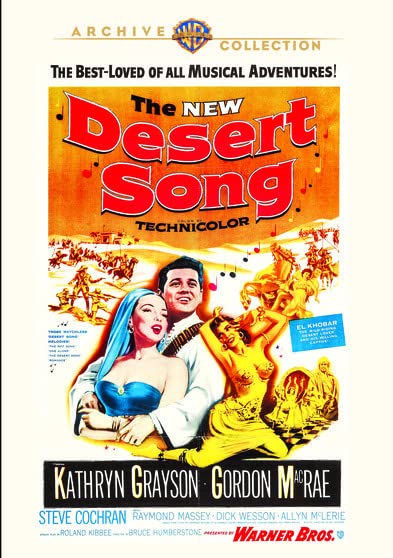

Ten years after the second feature-length American adaptation of the musical (or the fourth known filmed account from all-around, if you prefer), Warner decided to give their audiences the ol’ song and dance routine once more by producing yet another version – this time cleansed even further of any potential naughtiness and about as close to a Nelson Eddy or Dick Haymes flick as you can comfortably get without being slapped with a lawsuit.

Interestingly, just like the makers of every English-language adaptation of Agatha Christie’s Ten And Then There Were None made after the first 1945 Hollywood-ized film version has ever only, bizarrely, remade the earlier feature instead of sticking to its actual source material, 1953’s The Desert Song has very little resemblance to the play that beget it; snatching more elements of the previous variation(s). This version even carries over a song present in the ’43 version that was written by another party specifically for that film. Nevertheless, and perhaps even ironically, the ’53 film has become the better-known adaptation over the years. Mostly due to the fact that it was the only version available to the public (legitimately) for several decades.

Made just before Warner’s competitors down the street, Fox, introduced Cinemascope and widescreen formatting in general, The Desert Song was probably one of the last musicals presented in the old school Academy aspect ratio. But considering director H. Bruce Humberstone (oh, I hope that poor guy sued the shit out his parents) is very fond of his close-ups, particularly on soundstages made up to almost match the exterior shots that lead into them or in front of really bad rear-projections, I suppose we’re not missing much on that front. Additionally, nearly all of the musical numbers are changed and/or reserved solely for the movies leads, Kathryn Grayson and Gordon MacRae (the whole company sang in the original play).

And frankly, with that little diversity (did someone carry over the Nazi aspect to the musical department here, or what?), it gets even more tedious. In fact, I admit that my finger would hover gently over the Fast Forward button every time the dialogue started to die down and the music score began to swell up. But hey, it’s not all bad: MacRae makes for a good hero who wears glasses when he’s a scholarly professor and a red turban when he lead the Riffs as El Khobar, making him both Indiana Jones and Clark Kent in one. Steve Cochran is the French Captain vying for Ms. Grayson’s affection; the venerable Ray Collins is Grayson’s army colonel father; Dick Wesson is the cowardly Bud Abbott-style comic relief reporter who almost finds a girlfriend during this outing in co-star Allyn McLerie (Mrs. George Gaynes, who was in one of Mel Brooks’ films to feature both musical numbers and Nazis, thus establishing something resembling some sort of connection between everything I’ve been rambling on about since the beginning).

But the most inspired examples of casting here (or perhaps insipid, depending once again on your own personal distorted tastes) definitely fall to the selection of Raymond Massey as bad guy Sheik Yousseff, whose accent comes off as being closer to Russian than Arabic; Italian-American character actor Frank de Kova, who finally had a chance to play something other than a traitorous Native American for a change (and thus, was cast as a traitorous Riff); and – drumroll, please – William Conrad (for First Alert) in brownface as Massey’s slimy sidekick. A scene where Wesson picks up and pulls a classic wrasslin’ move on him, that of lifting the actor up over his head and spinning him around, is a genuine highlight, and something that would have never been done in Conrad’s later, heavier career.

The first feature-length film still officially missing (for the most part: a print does survive, albeit in black and white and minus a musical number), the folks at the Warner Archive have done the second-best thing in releasing the later film adaptations of the once-popular play. Available as separate titles, each version is presented in its original 1.37:1 aspect ratio with rather gorgeous transfers and audible mono English soundtracks. Neither release sports a special feature of any kind, which is a pity as I am fairly certain that there are bits and pieces of plants and birds and rocks and things still lying around somewhere from the two of America’s Desert outings (oh come on, you had to like that joke!).

Recommended primarily for classic musical lovers.