In almost every family, there is, arguably, a hidden sense of evil. When the soul gets twisted and corrupted, so does the trust, and even those closest to you are capable of signifying your doom, especially if it means getting everything they desire, or what they think they deserve.

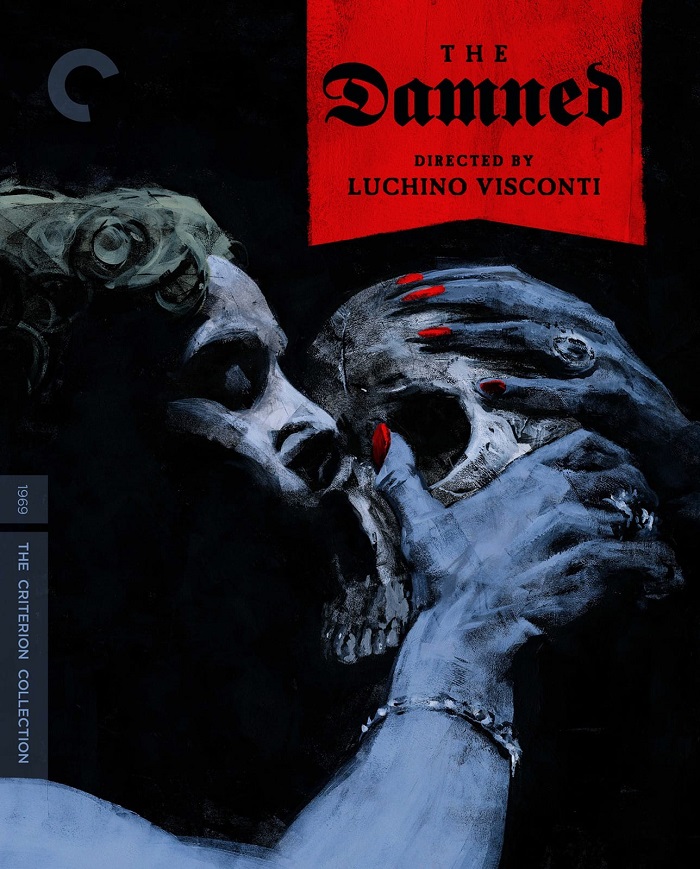

Celebrated and legendary Italian director Luchino Visconti orchestrates this demonstrative descent into family destruction with his controversial, incendiary, but deliciously stylized 1969 epic The Damned, which is now available from Criterion.

Set in the 1930s Germany during Nazism and Hitler’s unfortunate rise to power, the super wealthy Essenbeck family is willingly dominated by the Nazi party. The conservative patriarch Baron Joachim Von Essenbeck (Albrecht Schoenhals), the head of a huge steel company, is celebrating his birthday, which goes horribly awry when he is murdered. It turns out that devious social climber Friedrich Bruckmann (Dirk Bogarde) has carried out the murder by his lover Sophie von Essenbeck (Ingrid Thulin), Joachim’s diabolical daughter-in-law. By doing so, Martin (Helmet Berger), Sophie’s son, will take control of the family fortune. To make matters worse, Herbert Thalmann (Umberto Orsini), the family’s vice president, is framed for the crime.

As the film unfolds, so does the greed, indulgence, excess, and perversion, as the Essenbecks continue to go even further into the abyss. Eventually, Martin becomes the heir of the fortune, after being helped by Aschenbach (Helmut Griem), a leader of the SS, where he gives Friedrich and Sophie cyanide capsules, in which they willing take. They are both dead and Martin does the Nazi salute, signifying the definite end to the family.

Despite the film being universally acclaimed and Oscar-nominated for Best Screenplay, the film ran into trouble with the censors and was originally rated X due to the lurid elements: incest, pedophilia, rape, and homosexuality. In this case, it’s quite obvious, especially in some of the most uncomfortable moments: Martin seducing a little Jewish girl, where she later commits suicide; the “Night of the Long Knives” sequence where several of the Nazi officers engage in gay sex and are assassinated moments later; and the sex scene between Sophie and Martin. These are shocking scenes of dark side of humanity, but you have to give credit to Visconti for really going there. It makes you realize how sanitized and vanilla today’s films are compared to this.

The cast is uniformly excellent and willing to take risks, especially Berger who dons Marlene Dietrich-like drag in a memorable parody of Dietrich’s own breakthrough role as Lola in the 1930 masterpiece The Blue Angel. There is also Bogarde and Thulin in deliciously cunning performances, and the great Charlotte Rampling in a sympathetic role as Elisabeth, Herbert’s doomed wife.

The release from Criterion has some great supplements, including a 1970 interview with Visconti about the film; archival interviews with Thulin, Berger, and Rampling; Visconti on Set, a 1969 behind the scenes documentary; new interview with with scholar Stefano Albertini about the sexual politics in the film; and trailer. There is also a wonderful new essay by scholar D.A. Miller as well.