As sociologists, psychologists, and watchers of Buffy the Vampire Slayer well know, high school is a time of acute status anxiety. Your clique or cliques (jock, nerd, stoner, music/drama geek, brain, goth, emo, etc.) can almost totally define your standing within an invisible but powerful hierarchy. It can be horrible to be bullied and picked on, but it can be an even worse fate to simply be ignored.

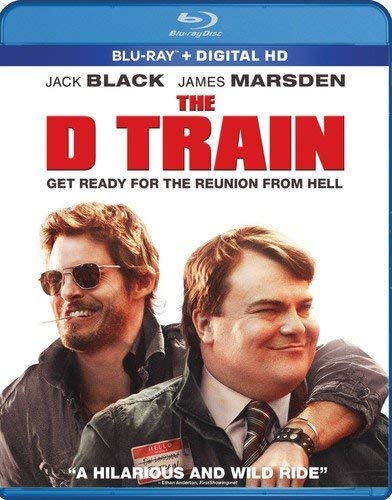

There are no flashbacks to high school days in the new Jack Black comedy The D Train, but its plot is powered by an impending 20th reunion, and for some people high school never really ends. Black’s character Dan Landsman and his fellow reunion committee members are rather desperately trying to drum up interest and attendance in the reunion, but apparently most of their classmates would prefer to let the past stay in the past. Landsman, self-deluded, self-important and self-involved, was probably ignored and/or barely tolerated in high school, and not much has changed. He styles himself the committee’s chairman, an imaginary position powered by his refusal to share the administrative password to the reunion’s Facebook page, but the other committee members still won’t invite him out for a friendly beer.

For whatever reason (The D Train is fuzzy about motivations and capricious with its characters’ psychological consistency), Dan has taken it as his personal mission to make the reunion a success. Perhaps it’s a way to rewrite his high school identity from annoying nobody to cool kid/hero. This despite the fact that objectively, he has done better since high school ended: he has an OK job, a pretty and understanding wife (Kathryn Hahn) and two kids, a 14-year-old son (Russell Posner) and a newborn baby.

It’s when Landsman sees classmate Oliver Lawless (James Marsden) in a commercial for Banana Boat that he hits on the killer idea: get the high school’s sexy bad boy to attend the reunion and his star-struck classmates will also flock to the party. With the gung-ho intensity that has become his comic trademark, Black journeys from Pittsburgh to L.A. to personally convince Lawless to attend the reunion. This section of the movie contains some of its sharpest and funniest scenes, as the desperately eager to please Landsman gets sucked into the clubbing, drinking, and drugging orbit of a very minor Hollywood player.

Marsden’s Lawless is at least as shallow and self-deluded as Black’s Landsman, but that’s so unremarkable in Hollywood as to barely be noticeable. He’s also something of a user, apparently willing to coast on his looks and ‘tude as long as they will carry him. The turning point comes when the bisexual Lawless seduces the doughy straight guy, sealing the deal with an intense kiss and the words Landsman has been panting to hear: “I’ll come to the reunion.”

Let me give points to co-writers/co-directors Andrew Mogel and Jarrad Paul for resisting the urge to turn this into a gay-panic comedy or to fake the sexual element of the bromance. Spoiler alert: Black and Marsden’s characters actually have sex; it’s not all a mistake, a dream, or a too-drunk-to-know-what-was-happening misunderstanding, as would be the case in a bad TV sitcom of yore.

Of course, Landsman is more than a little freaked out by just how far he was willing to go in pursuit of Lawless, but the crisis his walk on the wild side provokes is as much about social status as it is about sexual preference. That becomes clearer in the movie’s second half, when Lawless does come home for the reunion and Landsman, against his own better judgment, lets him stay at his house.

Complications, some comedic and some serious, ensue. The encounter meant very little to Lawless but it has reverberated in Landsman’s psyche. You would think he would be worried about Lawless spilling the beans about their same-sexcapades, but he’s the one who keeps (consciously? unconsciously?) pressing the point. His obsession with this handsome cool kid threatens his job, his marriage, and his relationship with his son (who is facing sexual pressures of his own), yet Landsman is the last to see the damage – much of it self-inflicted – that his desire to move up in the high school hierarchy is causing.

The problem is that while The D Train avoids some sitcom traps, it falls into a lot of others, mostly by removing the threat of real consequences from the characters’ actions. Comedies, even silly ones, can float away if there’s nothing real at stake. Landsman behaves horribly, and he does get a truly embarrassing comeuppance at the reunion itself, but the damage is ultimately minimal.

As an example: Black has involved his sweet-natured, technologically clueless boss Jeffrey Tambor in the L.A. trip, fooling him into thinking there’s a big, business-saving deal in it. The charade is so successful that Tambor finally brings the office’s technology into the 21st century and learns how to Google. (Again, the believability of these and other plot points seem more a matter of the screenwriters’ necessities than any version of reality.) So instead of destroying his boss and his workplace, Black has saved it.

The movie’s tone is all over the map as well. Mogel and Paul have numerous TV and movie writing credits, including for the Jim Carrey vehicle Yes Man, but this is their first directing job, and their inexperience shows. The D Train inserts just a few too many crazy, spoofy elements along with its character-based comedy. Scenes where we empathize with these desperate but recognizable people are interspersed with cheap gags that drag you out of the characters’ reality.

The actors do well. Black commits completely to his often unlikeable, reckless character, only rarely bidding for audience sympathy. Marsden looks and acts the part of a shallow guy who gets just a moment of recognition late in the movie, when he admits “I peaked in the 11th grade.”

The D Train is an unsatisfying movie overall but, like The Overnight and Dirty Weekend, it’s another acknowledgement in popular culture that male sexual preference is far less fixed than some might like to think. (If this gives unwarranted hope to gay guys dreaming of seducing straight men, I’m sorry, though if you’re as handsome and seemingly cool as Marsden’s character, you are likely to have a better chance with people of either sex.)

The message of The D Train, if it has one, isn’t really about sex anyway; it’s simpler and in some ways sadder. To all those losers and nobodies: don’t try to befriend the cool kids. You’ll only end up getting hurt.