As one of the great national cinemas, the Japanese movie industry has invented whole cloth many genres and excelled in many non-native filmic conventions… except arguably the Western-style horror movie. Until the late ’90s, when The Ring brought out a rather short-lived craze of ghost stories (usually with a long black-haired ghost, which is cribbed from Japanese folk-lore), Japanese example of horror were rather sparse, and rather different than Western films. In the West some of the acknowledged greatest movies of the silent era are horror films. There are several distinct studio and national traditions: Universal horror creatures, the ’50s and ’60s creature features, Hammer studios in England, giallo in Italy, which don’t find a real equivalent in Japanese cinema.

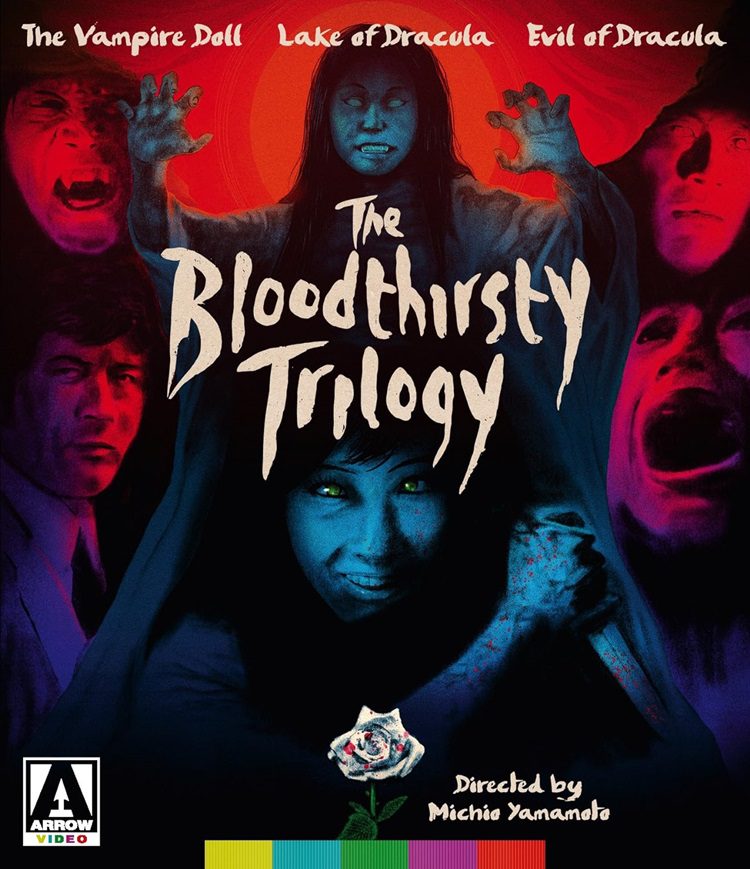

A possible exception might be from Toho studios, famed for Godzilla and other giant monster movies. While I think it’s a stretch to call those horror movies (at least after the first Godzilla), it’s not a surprise that this was the studio who produced The Bloodthirsty Trilogy, a trio of Dracula-inspired horror films, in the early and mid-’70s.

The most direct precedent for these specific films would seem to be the Hammer Dracula series which started in 1958, with Christopher Lee playing the debonair count against Peter Cushing’s Van Helsing. They were noted for their lurid bloodshed, explicit (for the time) sexuality, and specific period settings. All three movies in this set take place in or near Western-style mansions which could have come from a Hammer movie set, and each film has a least two scenes of copious bloodletting and gore. But, as Jasper Sharpe makes plain in his informative essay accompanying this Arrow Video release, these films are nothing like a direct adaptation of Western vampire stories. They are all set in contemporary Japan, and mostly borrow some images from vampire cinema while treading their own path.

While this set is called The Bloodthirsty Trilogy, and the theme of each movie is vampires, each is a distinct story rather than a follow-up. They are all directed by Michio Yamamoto, who besides these films and a handful of others in the ’70s mostly worked in television. The first film, The Vampire Doll, starts with a man just back in Japan looking for his fiancé Yuko, who lives in an isolated, Western-style manor far from Tokyo. When he arrives, he’s told she’s dead, but that night at the manor he sees her wandering the halls. He investigates…and is never heard from again. His sister and her fiancé go to discover what happened to him, and uncover terrible secrets dogging Yuko’s family, from their weirdly aggressive man-servant Genzo (played by Kaku Takashina, a familiar face from dozens of Nikkatsu action films) to why the lady of the house has a horrible scar on her neck. While there are ghostly and vampiric trappings, The Vampire Doll has less to do with Western-style vampires than it does ghosts and inexplicable supernatural phenomena, and it ends more like a murder-mystery than a horror film (though with an impressive gushing of blood from a neck wound at the climax.)

Lake of Dracula is more elliptical in its story-telling. It begins with a sequence where a young girl, Akiko, gets lost chasing after her dog and finds a strange house in the woods. An old man tries to grab her on her way in, there’s a corpse seated at a piano, and a man at the top of a staircase greets her with big fangs and a bad temper. Whether this really happened to Akiko, who we follow later as an adult, still chasing down her dog, or if it was a dream, even she is not sure. But when an enormous, coffin-shaped box is delivered to a house by the lake where she lives with her sister, strange occurrences begin to make her feel like she is reliving the dream, and maybe losing her mind. Lake of Dracula has more explicit vampirism than Doll, including a Renfield-like man-servant (Kaku Takashina again) and vampiric scions of the head monster. Akiko and her boyfriend (a doctor who coincidentally has to tend to the vampire’s victims at his hospital, where they have the disturbing tendency to leave their beds and jump off the roof) have to unravel the mystery before Akiko becomes the vampire’s next victim.

Evil of Dracula, filmed three years later and the final feature film of director Yamamoto, is the most conventional vampire tale of these films. Toshio Kurosawa plays Professor Shiraki, a teacher brought into a girl’s prep school and immediately offered the position of principal. The current principal is sick, and weak… often pale, you know. As if he was afflicted by some blood sickness (spoilers: he’s a vampire). And so is his wife who died recently in a car accident, but whose body is left in state in the basement. The girls all fall in love with their new teacher, who with the school doctor (played by Kunie Tanaka, another veteran of dozens of Nikkatsu crime films, including the Battles Without Honor and Humanity series) work to find out why girls go missing in their school.

The origin of the vampires in each of these films is interesting, and have to do with either a husband with a diplomatic career in Doll or tainted Caucasian immigrants in the two Dracula movies. The themes of the films themselves are not the same as Western vampire movies, which involve seduction, infestation, and invasion. Family relationships rear their heads in these trilogies, either about the lengths one will go to protect one’s family, or the bitterness that can be engendered by parental bias. As pure entertainment, The Vampire Doll and Evil of Dracula are the most fun, while I found Lake of Dracula to be rather shapeless and plodding, with weak dialogue, though the final act climax picks up the pace, the gore, and interesting imagery.

The Bloodthirsty Trilogy has been released on Blu-ray by Arrow Video. Besides the aforementioned essay by Jasper Sharp and trailers for the films, there’s a 16-minute video essay by Kim Newman on Japanese horror in general and the films in this set in particular.