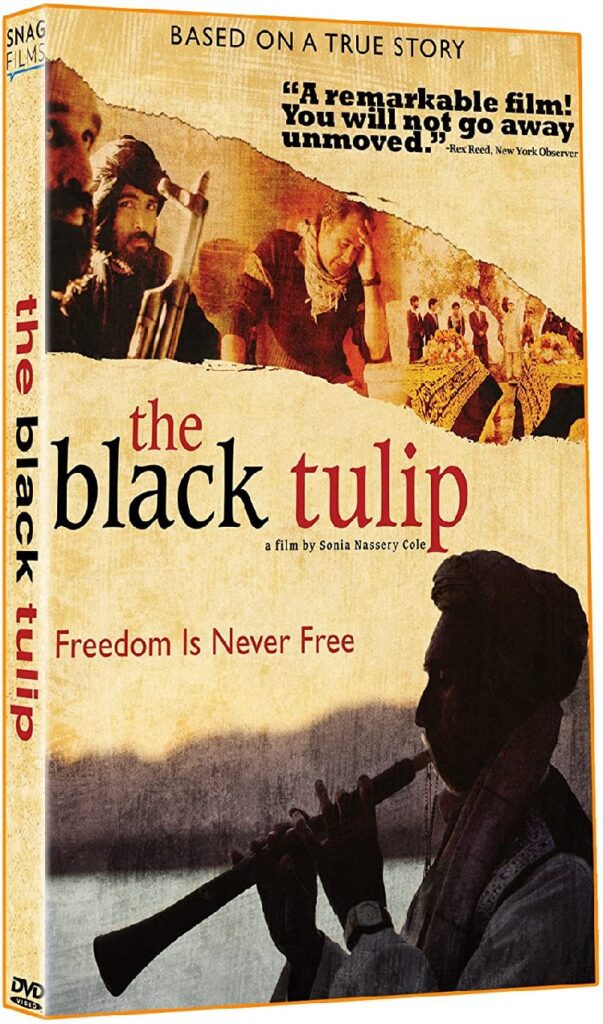

Directed by activist, director and actress Sonia Nassery Cole, The Black Tulip is Afghanistan’s official entry for the 2011 Academy Awards. The heart behind it seems impossible to discount (perhaps), but the overt and ham-fisted expression of desires that went into the film leaves a project that is cluttered, corny and sometimes cartoonish.

The movie proudly demonstrates some Afghani customs, like a game called buzkashi in which men on horseback fight over a goat, but ultimately fails to illuminate the social progress that is an understandable object of pride for the filmmaker. The oversimplification of many of the film’s elements, like the depiction of the Taliban as moustache-twirling pests and the thirsty urge to pair off female characters in romantic situations, undermines what could’ve been a poignant picture.

The film opens in Kabul in 2010 with the affluent Mansouri family opening a café called The Poets’ Corner. Hadar (Haji Gul Aser) and his wife Farishta (Cole) hope to make the place a gathering for newly-free Afghanis looking for a place to express themselves and get a bite to eat. Music is performed, along with poetry, and the Mansouri family bathes in hope for the future.

One of their daughters, Belkis (Somajia Razaya), is to be married to the love of her life Akram (Walid Amini). Their youngest daughter, Satara (Sadaf Yarmal), has a cute relationship of her own with Farouk (Masi Norry). Despite their burgeoning happiness, the menacing Taliban is always right around the corner serving as a reminder of the Dark Ages – even if their presence in an alcohol-serving café is dubious on its face.

That the Afghans would celebrate their newfound freedom is pretty sensible, but The Black Tulip presents this as an undisputed, unsophisticated reality. Little distinction is given to any of the characters and Cole’s insistence on proudly displaying customs is one-dimensional and dull. When dramatic tension does arise, it feels baseless and surprisingly trivial.

Cole seems to have learned many tricks from American filmmakers – or perhaps, more accurately, American soap operas – and she applies them generously. There is lots of slow-motion camerawork during romantic scenes and shot-framing is often ungainly. Despite the rich colours and social tapestry on display, Cole’s unadventurous approach does little for Afghanistan as a theme.

As much as The Black Tulip reminds audiences that the Taliban is still a force in modern Afghanistan, its careless approach provides little room for thought. The upshot of the wedding scene is drawn with bushy lines, for example, and plays out more like a mob attack than a manifestation of religious fundamentalism. And a mother’s sorrow is less an organic expression of grief than yet another opportunity for political platitudes.

The screenplay, written by Cole and David Michael O’Neill, is opportunistic. Almost every line of dialogue is a blatant expression of political will and very little about The Black Tulip feels human. By presenting its subjects in such general fashion, it does the film a crucial disservice.

The performances are in line with this disservice, with awkward acting doing little to rise about the hammy, forced material. Cole and Aser come across as Afghan versions of the Huxtables, meeting tragic conditions with little more distinction than to utter “It will get better; I have dreams.”

The Black Tulip is a disappointment. It may be tempting to give the picture a pass based on its subject matter and purity of heart, but as a film it is little better than the most rudimentary and manipulative of Hollywood’s dreck. From its mandatory humour to its dependable oversimplification, Cole’s motion picture is a lumbering and unsophisticated experience.