Written by Kristen Lopez

When controversy springs up about the effects of American movies on the nation’s children, people respond in kind or roll their eyes. Movies are fictional, and anyone who doesn’t know that shouldn’t be watching them, right? In a way, Joshua Oppenheimer’s chilling documentary, The Act of Killing, is an exploration of the effects of American movies on the world’s children, and the results are surprising. Outside of the myriad of questions revolving around history and entertainment, the story follows a group of mass murderers coming to terms with atrocities they committed. The Act of Killing is a necessary piece of filmmaking, leaving the audience to cope with Oppenheimer’s subjects in conjunction with Western audiences’ reception to the material.

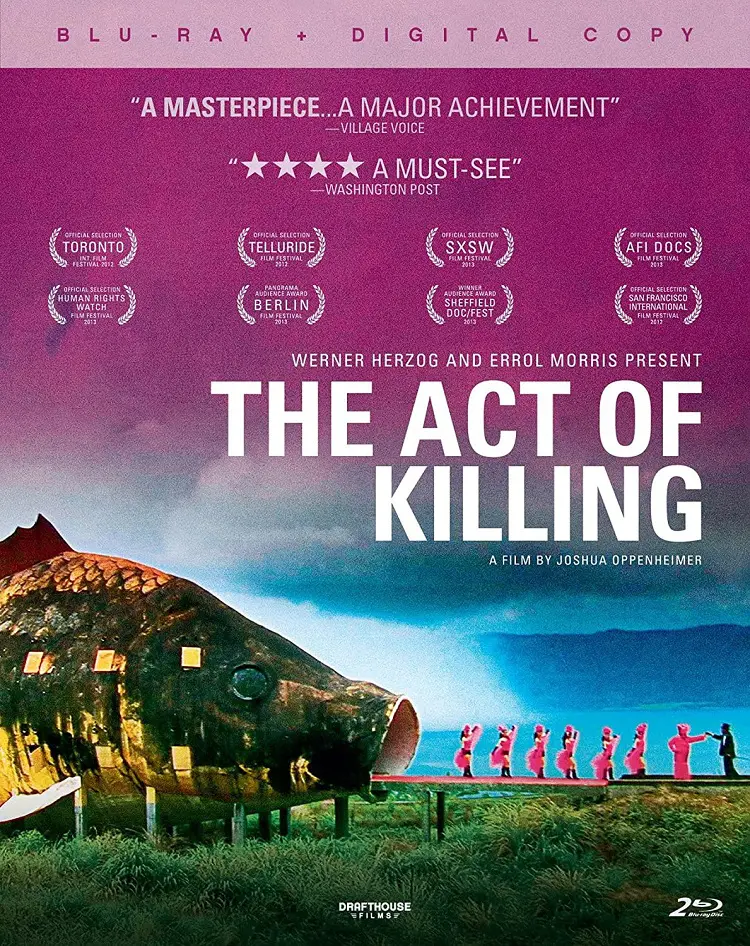

In the mid-1960s, Indonesian death squads tortured and slaughtered millions of suspected Communists and Chinese citizens. Today, the events are all but forgotten, or at least quietly considered the acts of war. Oppenheimer interviews various paramilitary leaders, and head executioner Anwar Congo, offering them the opportunity to make a movie recounting the atrocities they committed in any film genre they wish. The completed film, and the men’s reception to it, presents a startling commentary on filmmaking and historical significance.

Watching The Act of Killing is an experience in and of itself. The men assembled, led by the grandfatherly Anwar Congo, remain flippant about their past for a majority of the movie, laughing and smiling as they recount torturing people. When attacks of conscious pop-up during filming, the various men mitigate the circumstances by explaining they believed the Communists were just as cruel, rationalization and distancing themselves from the events becomes the only way to cope. As the events of the reenactment intensify, including a recreation of a village massacre, the men struggle to cope with events. Anwar Congo is never wholly sympathetic by story’s end, nor does Oppenheimer expect to showcase an act of redemption. Even in the end, when Congo goes to the location where he tortured people and tries in vain to vomit, a glimmer of falsity remains. Is Congo continuing to distance himself, forever acting in his own mind? When Congo is placed in the victim’s seat and a recreation of him being slaughtered happens, it’s the one moment where Congo’s façade shatters. He refuses to do it again and asks Oppenheimer if he’s sinned for his actions? The movie’s intent isn’t expressly portraying these men as monsters or heroes, but to force them to explore how their actions affect them.

The multitude of layers within The Act of Killing are poignant and from a Western standpoint the documentary forces you to question the separation between art and reality or if any exists. The audience is confronted with the indifference of life and death, but is safely removed from the horrors by watching them reenacted on screen. Various times throughout, characters comment on it being “only a movie” despite having lived through the acts themselves. In a way, being separated from events is similar to history itself. The youth of Indonesia are told to never forget why the crimes were committed, but they lack the ability to process the horrors themselves because they haven’t witnessed anything on that level. Furthermore, the use of moviemaking to mitigate violence lessens the impact of events for the real people involved, the executioners who constantly wonder whether they’re not making the Communists look good by default.

“History is written by the winners” is a line spoken in the movie, and if anything The Act of Killing casts a harsh eye on America. One of the gangsters discusses how countries change the definition of war crimes after the atrocities have been committed, citing Bush’s opening of Guantanamo Bay as an example. For a small county like Indonesia to hit the nail on the head about our own rewriting of history and the lack of punishment for particular crimes proves heart-wrenchingly true. The use of Western influences is present throughout, with various shots of American consumer goods and businesses populating Indonesia, meanwhile the majority of the country’s people live in tiny villages. This a country that reveres all things American, going so far as to believe our movies perpetuate an American dream involving killing and murder. Ironically, The Act of Killing looks to have Oscars coming to it, but it is a documentary excoriating American filmmaking. Congo and his crew continually mention the word “gangster” means “free man,” and how gangster movies starring Al Pacino and the like perpetuate a dream wherein anything is possible if you’re willing to commit bloodshed for it. We see this within our own American pop culture, Scarface revered as the rapper’s dream, an idea horrendously skewed in global markets leading the audience to ask what message our country is making through its popular culture. Are we rewriting our own history and pushing out our own flaws? How do other countries perceive our country through our images? It’s a documentary not just exploring a country’s atrocities committed over 40 years ago, but our own nation of filmmaking and treatment of other country’s problems.

The Act of Killing is a scorching documentary leaving you to question the intent of movies themselves. One cannot be a passive viewer of Oppenheimer’s documentary; you have to engage with it through your own experiences just as Congo and his group do. The various leaders of these crimes remain in power today – a lingering question is, if the crimes were so horrible, why weren’t they punished? – and sadly, this documentary proves the country will probably never get justice for the dead; the history of Indonesia’s war crimes are too ingrained in the culture, just as America’s view of the gangster are. Horrific, incisive, and shocking, The Act of Killing only needs to be experienced once to achieve its goal.