Ever since I can remember, I’ve been fascinated by serial killers. There is something so uniquely interesting about someone who murders not for money, revenge, jealousy, rage, or any other understandable motive but for the pure pleasure or murdering itself. It is of course horrendously horrible, but terribly fascinating as well.

One such person I’d not heard of until I watched this film was Fritz Haarmann who lived and killed in Hanover, Germany in the period between the World Wars. He sexually assaulted, mutilated, dismembered, possibly ate, and almost certainly sold for meat a minimum of 24 boys all while working for the police as an informant.

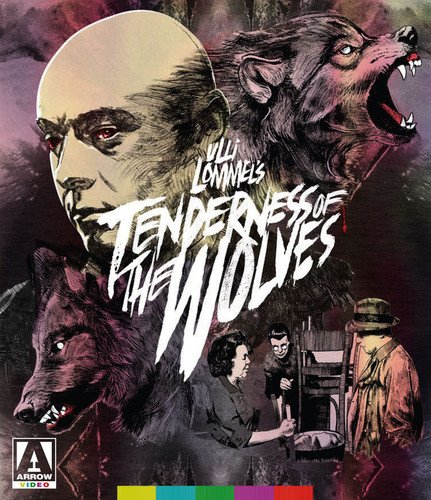

In 1973, Rainer Werner Fassbinder proteges Kurt Raab and Ulli Lommel made Tenderness of the Wolves based upon the life of Haarmann. It is not the blood-filled gore-fest you might expect from the subject matter (or Lommel’s directorial output over the last couple of decades). There is very little violence at all. In fact, there is more full-frontal male nudity than blood, which might tell you all that you need to know.

Neither is the film all that concerned with the psychology of Haarmann. They give us no information about his early life nor his criminal career (he served short prison terms for larceny, embezzlement, and assault) prior to becoming a serial murderer. They don’t try to explain why Haarmann became the brutal killer he was at all.

If there is a theme to the film, it is that when your country is filled with poverty, rampant unemployment, and a severely underfunded government as Germany was at the time, then you will have a populace that turns to crime and people like Haarmann shall be allowed to flourish. Germany between the wars was such a place, and it turned a blind eye to very real monsters like Haarmann for many years.

Interestingly, the filmmakers were on such a tight budget (they were basically using leftovers from a grant Fassbinder was given from the government) that they couldn’t afford to recreate the look of 1920s Germany so instead they set it just after World War II, although these modern eyes couldn’t tell you the difference. Curiously, they put in an end note telling the audience the real Haarmann was executed in 1924 many years before this film is set.

Though I’ve never seen a film by Fassbinder, I can still see his fingerprints all over it. That doesn’t make any sense except that Fassbinder was firmly set in the New German Cinema period which was greatly influenced by the French New Wave and this film certainly has that sort of feel to it. It’s drenched in realism and yet there remains a certain theatrical element to it. The staging of scenes and the lighting (by Jürgen Jürges) all look like they were done upon a stage.

Fassbinder was busy staging a play at the time in another city, but took time out to play a small role in the film. Most of his roving company were involved in this film, both in front of and behind the camera, which no doubt gives the film that Fassbinder film even if he wasn’t as hands on with it as with other productions. They say due to the graphic nature of the story he initially kept his name off of it as well (which in itself is odd considering his other films and his oversized personality), but once the film garnered some acclaim he tacked it right back on.

It is Kurt Raab who is considered to be most responsible for the film as it was his idea to make a film about Haarmann, he wrote it, and stars as the killer. His version of Haarmann is a bit queer in every sense of the word. He maintains an affair with his criminal partner Hans Grans (Jeff Roden) while simultaneously using his police credentials to lure young men back to his apartment where he seduces, rapes, and often murders them. Raab plays him with a certain aloofness. He is tender and sometimes charming but never terrifying (well at least not until he rips their necks out with his teeth).

The story follows him as he and Grans commit petty crimes like pretending to be working for a clothing charity only to barter the donations for other goods. It’s never stated outright, but certainly it is implied that he often takes the clothes off of those he murdered to sell, and the meat he’s putting into the black market tastes suspiciously like murdered boys.

His friends (and the police) are happy to help him commit the smaller crimes while turning a blind eye to his obvious darker side. When two of the characters see a clearly dead and naked boy lying on Haarmann’s bed, they ask few questions and readily accept his lame reasoning that the boy is simply ill. Again, the film is more interested in these social constructs developed through poverty in a country wrecked by war than the lurid details of a crazed killer.

Arrow Video has once again brought us a relatively obscure, definitely non-mainstream foreign film to our homes in the greatest of possible ways. The Blu-ray was scanned and restored from the original 35mm camera negative and it looks great. There were a few noticeable scratches and the normal grain found in these sorts of things, but the colors and blacks looked outstanding. Likewise, the audio is clear and crisp with the Brahms led soundtrack sounding particularly nice.

The disk is filled with extras. There is an interesting audio commentary by director Lommell as well as interviews with cinematographer Jürgen Jürges and one of the actors. Author Stephen Thrower brings an appreciation of the film, which is essentially a video of him talking lovingly about it for nearly an hour. It also comes with a reversible cover and a nice essay.

Tenderness of the Wolves is an oddly beautiful, rather fascinating film. It will likely offend the masses, bore horror fans looking for more blood, but the art-house crowd will love it. For me, it was a fascinating look both at New German Cinema and Germany at one of its darkest periods.