John Schlesinger’s Sunday Bloody Sunday (1971), the highly anticipated follow-up to Midnight Cowboy (1969) is an honest, often somber, account of what lovers will tolerate and forfeit in order to retain who and what they believe they want. To drive the point home in a most poignant way, screenwriter Penelope Gilliatt created a love triangle in which fancy-free youth dominates at the top of the pyramid, and the slightly older, more experienced parties who find themselves predisposed to yearning are tucked uncomfortably at the bottom corners.

Our lovelorn pair serving as the triangle’s foundation includes Alex Greville (Glenda Jackson), a thirysomething divorcée who’s gathering sufficient courage to leave her job at an unemployment office, and Daniel Hirsch (Peter Finch), a doctor with an candid, upbeat bedside manner who has no qualms about being a gay man in Britain, where “homosexual acts” between men in private were legalized only four years earlier, in 1967. Bob Elkin (Murray Head), their mutual love interest, is an installation artist in his twenties who longs to sell his big ideas on a much larger scale in New York, where he believes his career would flourish more quickly than it would in London.

Among this group Bob is the lucky party endowed with the innate ability to live in the moment. He is so self-involved that he’s somehow able to draw people to him as if magnetic, but can maintain enough emotional distance to ensure that his ambitions are never thwarted. It’s painfully obvious that Alex and Daniel each cling to the belief that their respective relationships with him are special enough to shift his thought process in their favor, but young go-getters with no discernible baggage seem to propel themselves through space and time unaffected, as Bob’s partners soon learn.

It’s a rather quiet little love story devoid of excessive steamy scenes, screaming outbursts, and spine-chilling plot twists involving one of the lovers being in mortal danger. It should be completely dull, except that the period in which the film is set and was written adds dimension to the story and characters, as do Alex and Daniel’s personal histories, and the friends that surround them. There’s economic turbulence; freedom to love whomever, however, whenever; and schoolchildren running about accusing their parents’ friends of being bourgeois. Alex, who deflects said accusation when tending to her friends’ brood for a few days seems as comfortable with the family’s bohemian, small-children-toking-reefer, end-famine-poster-in-the-kitchen way of life than she is with committing herself to a man she knows is seeing another man. However, she understands that the state of society is not the same as when she was married. If a previously married woman wants to snag a hot young thing, she needs to accept the life that a hot young thing leads. Of course, having grown up in a seemingly conservative, well-to-do household during wartime, her sense of freedom and spontaneity is a bit stifled.

Daniel’s Jewish upbringing forces him to lead a closeted life around his family and family friends, but he is otherwise solid about his lifestyle and carries on professionally in an unassuming manner. This is particularly important because, as Schlesinger’s nephew, cultural historian Ian Burma, wrote in “Something Better,” an article featured in the fantastic Blu-ray booklet, prior to Sunday Bloody Sunday gay characters were almost always depicted as deviants. Instead, Schlesinger offers an attractive, congenial do-gooder as his gay protagonist. Also normalizing, as it were, is the way that specific kissing scenes between Alex and Bob and Daniel and Alex were shot to look very similar, as if to say, “No big deal, people of 1971; love is love.” But despite the message that love is genderless, there’s no mistaking that it can be downright sobering. It is when Bob decides to leave that Alex and Daniel must finally come to terms with need versus want; it’s also when they’re forced to define what love really is and assess whether or not it actually exists in their lives.

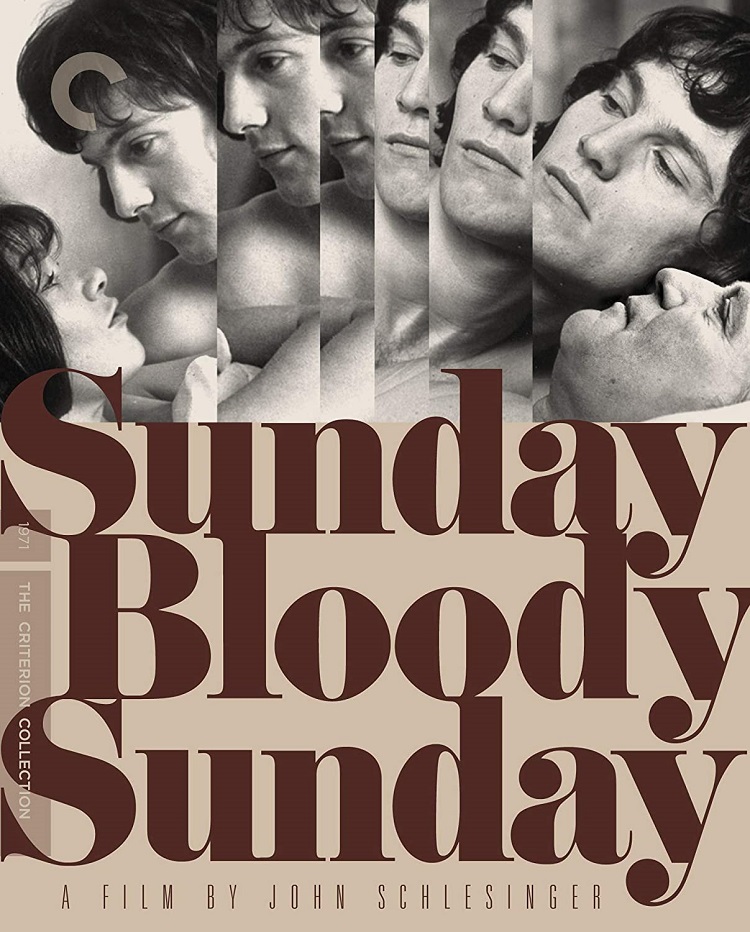

After viewing the film, definitely take the time to read Burma’s contribution to the booklet, as well as the reprint of Penelope Gilliatt’s “Making Sunday Bloody Sunday,” in which she offers interesting insight about casting and her working relationship with Schlesinger. In addition to the restored high-definition digital transfer, the Blu-ray also features interviews with director of photography Billy Williams, Murray Head, production designer Luciana Arrighi, biographer William J. Mann, and Schlesinger’s life partner Michael Childers.