As the middle of the 1960s approached, American cinema bid two of its mightiest moneymakers a small, barely-audible adieu. First and foremost was the genre of classic western film, which had been done so many times since the motion picture industry had established its firm roots in Hollywood that studio executives eventually had to come up with box office ploys such as CinemaScope in order to keep audiences coming in instead of tuning in to watch Rawhide at home on the TV set. The second was that of CinemaScope itself; a procedure that every other studio had taken to copying in what we commonly know today as just plain ol’ widescreen. And it is in the instance of Son of a Gunfighter that we witness several deaths.

On the one hand, we witness the demise of CinemaScope, Son of a Gunfighter being the last movie released to advertise the gimmicky widescreen moniker. Additionally, we see the final theatrical offering from director Paul Landres – who was a regular contributor to the western, though mainly for projects manufactured especially for the small screen. But is in the noticeable, mercilessly slow death of the American western itself – visible throughout every frame of Landres’ Son of a Gunfighter – that we simultaneously witness signs of the genre’s European rebirth. An anti-hero with no time for love or remorse. A vice of violence. The promise of death without so much as a hint of salvation.

While the Euro western vibe could be attributed to the fact Son of a Gunfighter was filmed in Spain with a number of local cast and crew, it’s very interesting to note that its only credited writer was another veteran of American television: one Clarke Reynolds. Either Mr. Reynolds foresaw the future here, or he was privy to an advanced international screening of A Fistful of Dollars – which, though filmed roughly around the same time as Son of a Gunfighter (the movie’s actual onscreen copyright date reads 1964, while the IMDb has it down as a 1965 production), didn’t reach American shores until 1967. (Similarly, the violent-for-its-time Son of a Gunfighter didn’t earn a general release until 1966, once again according to the prone-to-being-fallible IMDb.)

Of course that is mostly all just speculation on my part, folks, but looking at the cold hard truth of the matter leads us to the same conclusion either way you cut it: Son of a Gunfighter was not your average cowboy picture for America circa 1964(/65/66).

A great example of its atypical behavior is quite noticeable in one memorable scene involving Kieron Moore – a handsome, strong hunk of eye candy who would normally be the hero. Or at least the hero’s pal. Instead, Moore plays a half-Mexican/half-Texan deputy who is spiteful over the way he has been treated all of his life for his mixed heritage. Unable to fit in anywhere, makes a foolish deal with the devil of the story (as played by the great Aldo Sambrell, one of the few European actors to appear in all of Sergio Leone’s major contributions to the newly reinvented genre), only to let his greed get the better of him; to wit he betrays everybody he can once the opportunity arises.

And so, Moore is left in the desert (shirtless, at that) tied to several stakes in the ground, with a wet piece of rawhide around his neck; a tanned strip of leather that will eventually tighten and dry as the sun bakes his body. The method of torture, not the kind we regularly see in film, would normally conclude with a serendipitous rescue. In Son of a Gunfighter, however, nobody comes to save the day – and Moore is left to die alone with only his guilty, bitter conscious to keep him company. I’m reading quite a bit into that, needless to say, as the actual scene (which Sambrell promises him if he does the wrong thing early in the picture) is a short one; director Landres determined to get back to the action of the story’s actual hero.

Said hero, incidentally, is a young fellow named Johnny – played by Russ Tamblyn, who was no stranger to the west at this point in time, and who would later reprise the role (or rather, be given the same title) via a cameo appearance in Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained, where his role was credited as “Son of a Gunfighter”. (Tamblyn’s lovely daughter Amber also appeared in the film, her briefly-seen character called “Daughter of a Son of a Gunfighter”.) Here, Tamblyn sheds a part of his family-friendly reputation as another spiteful character: this one quick with a firearm and fueled by a burning hatred to avenge the man he holds responsible for the death of his mother.

Along the way to the Mexican hideout of his arch nemesis, Ace Ketchum – an outlaw whom we later learn has more in common with our protagonist than he’d care to admit – Johnny is injured by a run-in with the men of Juan Morales (Sambrell), leader of a group of local bandidos. Taken in by rancher Don Pedro (Fernando Rey), the cute gringo catches the fancy of the Don’s daughter, Pilar (María Granada), who does her best to put out the fire of hate in Johnny’s eyes. James Philbrook, though unseen for a majority of the picture, is the villain Tamblyn has it in for, and who adds a unique spin to the climax after a certain deputy’s nefarious actions put everyone in danger.

With an explosive finale and many a bloody gundown under its belt, Son of a Gunfighter also stands out for some very odd cinematography (which was either experimental or amateurish, it’s hard to say) and a rousing musical score by songwriter Robert Mellin. Hopefully, a soundtrack will surface someday, as it’s really a wonderful and out-of-the-ordinary selection from the man who is perhaps best known for his hits “My One and Only Love” and “Stranger on the Shore”.

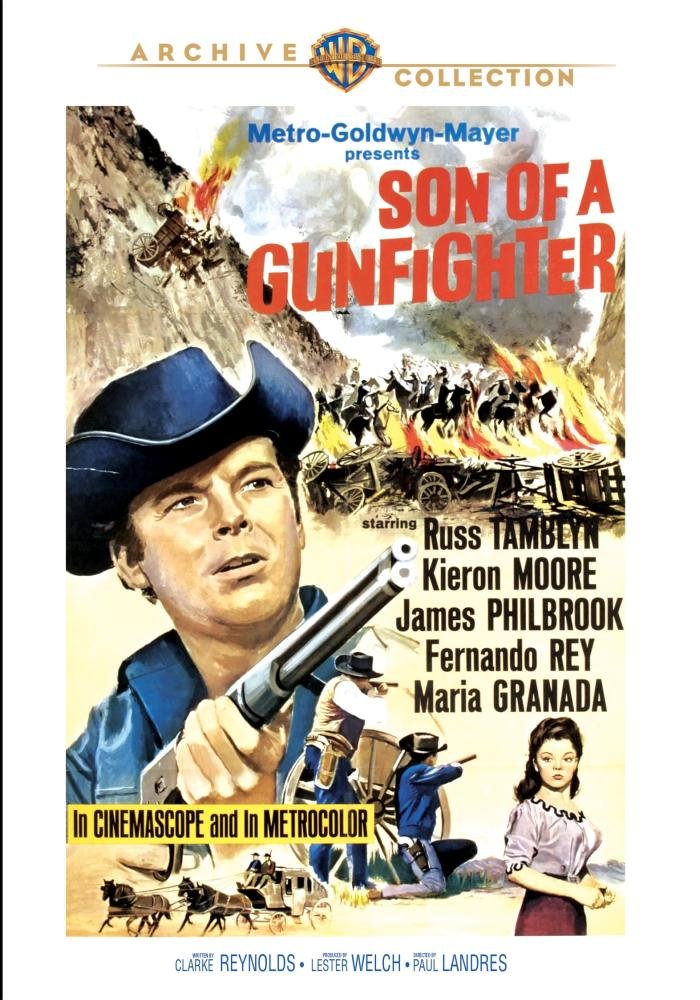

Presented in an anamorphic widescreen 2.35:1 aspect ratio, the Warner Archive Collection’s release of Son of a Gunfighter boasts a fine print that shows off the film’s ’60s-style Metrocolor palette (the MOD DVD’s artwork erroneously lists this as a B&W feature) admirably. The image looks as if it has been slightly stretched out a bit to my well-trained eyes, but it’s hardly distracting. The accompanying mono English audio track (the European performers either looped their own dialogue in post-production or were dubbed by others) is quite clear, and a 4:3 widescreen trailer for the film (which looks like it could have been taken from a video source) is included as a welcomed bonus item.

Making its long overdue home video debut in the U.S. (and probably the world, for that matter), the Warner Archive has done a huge favor for fans of latter-day American westerns and early Euro westerns alike with this transition piece from the MGM vault that has gone largely ignored for the last fifty years (or so, depending on when the movie actually was finished). While just about every element of the title has since been remade (and even referenced) since the movie first hit screens back in the mid ’60s, Son of a Gunfighter itself has remained rather elusive since then. Thankfully, we are now able to see this one for ourselves in all of its unique (possibly trendsetting) glory.

Recommended.