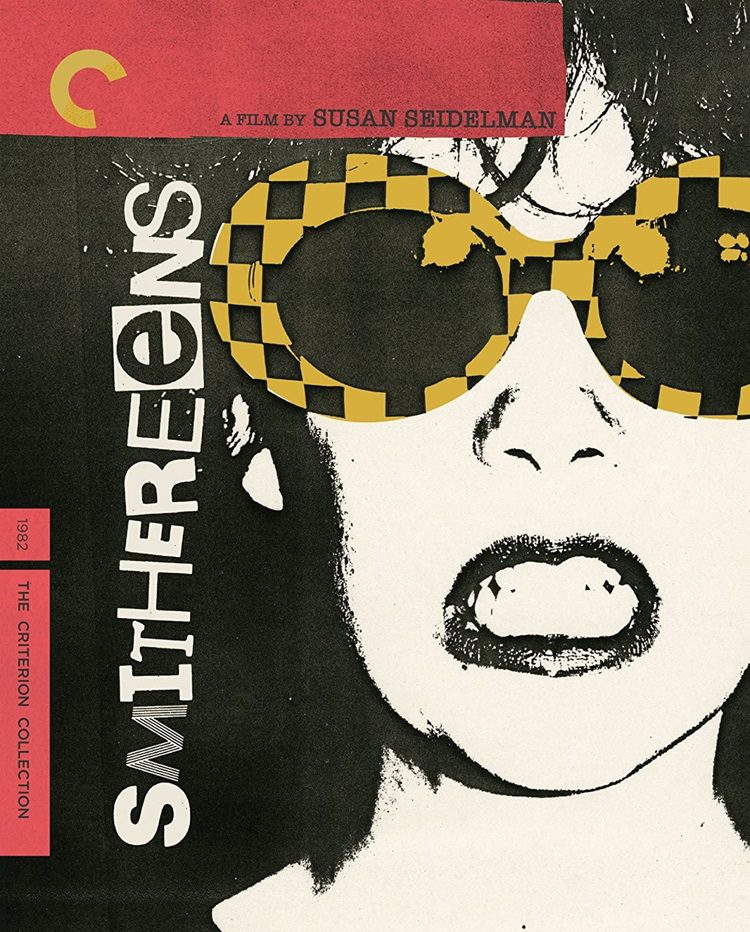

Films about women by women are pretty rare these days. These are stories about women taking control of their lives and reinventing themselves. Most filmgoers miss out of the opportunity to see and relate to characters who turn out to be just like them; characters who are just as self-absorbed, rebellious, and determined just like everyone else. Thankfully, there is director Susan Seidelman’s landmark 1982 grassroots classic, Smithereens, which shows us what we’re missing in film: the feminist touch. It also paints a low-key, but documentary-like portrait of the grim, desperate side of underground New York in the early ’80s.

The story centers on Wren (Susan Berman), the ultimate punk heroine, who comes to New York after escaping New Jersey with the mission of becoming famous. When she isn’t posting self-promotional flyers of herself or barging into the Peppermint Lounge, she finds herself torn between nice guy Paul (Brad Rinn), who lives in his van next to the highway, and detached rocker Eric (Richard Hell), a married man who eventually leads her astray. In the end, she finds herself alone in a cold and brutal world that just may chew and spit her out.

This stripped-down snapshot is a really sad look at a woman who uses people for her own gain, but in the end gets a taste of her own bitter medicine. Wren is one of the seminal antiheroes of underground because you do have sympathy for her, but there are other times where you just can’t stand her. She’s a complex woman surrounded by people who may be way more put together than she is. Berman is a force in fish-nets, but the other actors are a little hammy with their characters. Be as it may, they aren’t terrible actors, but you can tell that they are amateurs from a student film. This is actually a good thing because they don’t distract the viewer from the realism of the film.

There is also the matter of how it signals the end of the punk movement, but with a moody and blazing soundtrack. It successfully meshes well with every scene in the film. Punk music may be dated or ancient history, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it actually came back with a vengeance.

I am glad that Criterion released the film because it was a major discovery for me. The picture and sound quality looks great and cleaned up. The supplements are a little slim but they make up for that. They include:

- Audio commentary from 2004 featuring Seidelman

- New interviews with Seidelman and Berman

- Two early short films: And You Act Like One Too (1976) and Yours Truly, Andrea G. Stern (1979), which were made by Seidelman when she was a student at NYU.

As usual, there is a great new essay, this time by critic Rebecca Bengal.

I wish more people who take a chance on films like this. They’re missing out of new gems and discoveries made by filmmakers who really want to tell their stories in their own unique ways. Honestly, Smithereens represents indie filmmaking at its most raw and unpolished.