Shock is the final film that Mario Bava directed and is commonly regarded as an underwhelming swan song. He was one of the progenitors of the giallo cinematic genre, with his Blood and Black Lace a template from which a number of imitators had built their own careers in that genre. Shock, at least superficially, comes from the horror genre that many of those imitators had evolved their craft towards. Dario Argento and Lucio Fulci moved from the suspenseful murder mysteries that Bava had so skillfully helmed to full out supernatural horror.

Shock, at least at first glance, seems to be the old master’s attempt to work in the wheelhouse of the directors that followed him. It even stars Daria Niccolodi, Dario Argento’s long-time paramour who had starred in that director’s own Deep Red. And from a story overview, it has elements that seem largely cribbed from other stories. Repulsion is a major touchstone (though when I was watching the film, The Shining was what I was reminded of, which wouldn’t come out for three more years… so points to Bava.)

Daria stars as Dora, a widow who has remarried and has come back to the house where she lived with her first husband after several years absence. She brings with her the son from the first marriage, who was either a baby or not born when his father died (this, like many story elements, isn’t clear). Her second husband, Bruno, is an airline pilot and frequently away. Daro has misgivings about going back to the house where her previous husband committed suicide, but Bruno insists it’s the best thing for the family.

However, almost immediately upon coming to the house Daro’s son Marco begins exhibiting some upsetting behavior. He takes to hiding in places around the house and jumping out to startle his mother. He sets up what seem like traps to injure her. He talks to people who aren’t there. Only Daro, and the audience, ever see this disturbing behavior… and this is one of the places where Shock is shaky as a story.

We see Marco on his own very early on in the film, talking to nobody there. To any seasoned horror fan, this means there’s either ghosts or the kid’s getting possessed, no question. As the film progresses, however, we’re led to understand that Daro’s anxieties might be the cause of her growing fear of her own son. If the film were entirely from her perspective, we as an audience would feel free to question what was happening. Was Marco being held by the spirit of his dead father, or was Daro’s mental state causing her to misinterpret childish misbehavior as malice? That is certainly Bruno’s perspective.

But we frequently see Marco alone, without the filter of Daro’s perspective, with creepy color contacts and odd, very un-child-like expressions on his face. The question of possession might be a radical one for the characters. For us watching, it’s a no-brainer, so there’s very little suspense involved in the mystery. We just want to see how it evolves.

Which is slowly. Roughly the first half of the movie involves the family moving in, Marco being a brat, and nothing really happening. The backstory of the first husband’s suicide is slowly revealed, perhaps too slowly because once revelations about it come to the fore, they aren’t that surprising to an active viewer.

Mario Bava is best known for his suspense sequences, and his stylistic use of color and framing. Shock is always stylishly and interestingly framed, but none of the colored-gels or unrealistic but evocative lighting is present in the film. That sort of imagery might be considered “stereotypical Bava” (to the few cinema fans who have a stereotype of a relatively obscure Italian filmmaker’s style) but it was wholeheartedly appropriated by his followers like Argento. Shock takes a more realistic approach to its visual style.

That doesn’t mean that it is flatly directed. Bava consistently picks interesting framings and fluid but not showy camera movements. This and the editing make even a leisurely paced film like Shock consistently visually evocative. It isn’t as lurid or showy as his ’60s output, but it is all skillfully directed.

The screenplay is a little more muddled. At some points, it seems everybody might be possessed by the dead spirit of Daro’s husband. Or she might be mad. And the disturbing implications of the son taking up his father’s interest in his mother, including sexually, is brought up and dropped without much of a resolution. Shock is full of ideas, but not that full of follow-through.

It does have shocking moments, living up to its title. And the final sequence is a mix of horror and suspense that proves even at the end of his career Bava deserved his reputation. He was a consummate craftsman who could take even a muddled story and make it effective for an audience. There are several bravura Bava moments in the film. It’s not a great Italian horror film, however. Perhaps underrated, since it is the final film of a cinematic master, Shock is not some kind of disaster. It’s actually a fitting tribute to a diligent, hardworking craftsman in the art of cinema.

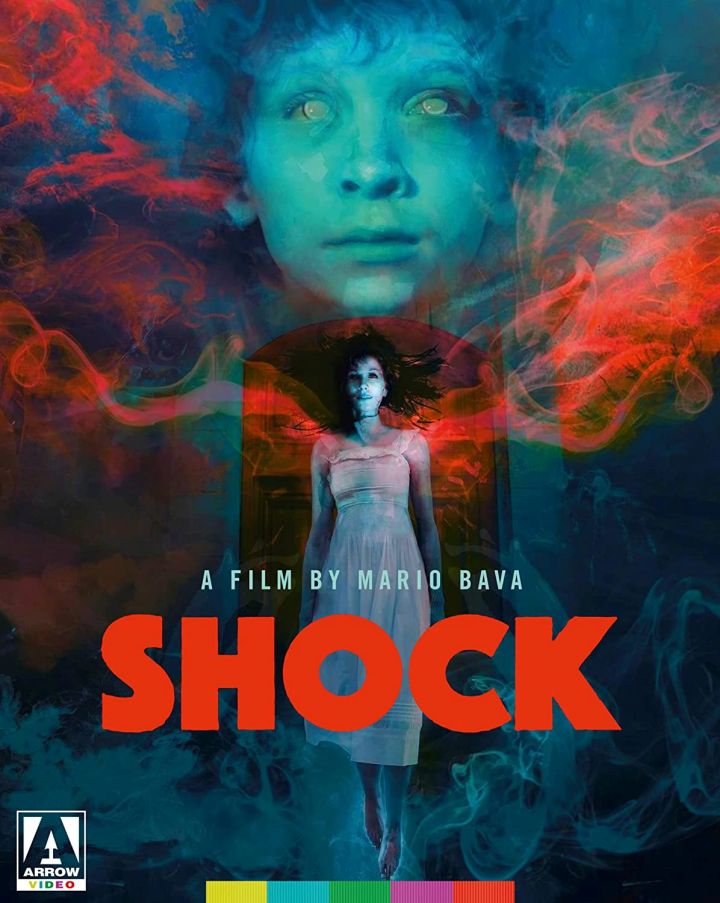

Shock has been released on Blu-ray by Arrow Video. It includes both Italian and English language tracks. Extras on the disc include an audio commentary by Tim Lucas. Video extras include “A Ghost in the House” (31 min), a new interview with Lamberto Bava, Mario’s son and co-director; “Via Dell’Orologio 33” (34 min), an interview with co-writer Dardano Sacchetti; “The Devil Pulls the Strings” (21 min), a visual essay by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas; “Shock! Horror! – The Stylistic Diversity of Mario Bava” (52 min), a video appreciation of Bava’s work by Stephen Thrower; “The Most Atrocious Tortur(e)” (4 min), an interview with critic Alberto Farina. There are also trailers and TV spots, and an essay in the booklet by Troy Howarth.