Charlie Anderson (James Stewart) is a good man. He’s built a big, beautiful farm in Virginia. He’s raised six sons and a daughter nearly by himself. His wife died many years prior. He takes his family to church every Sunday. They might always be late, and he might only go because he promised his wife he would before she died. But he goes. He’s respected in the community but he stays out of the way. When he prays, he talks about how hard he has worked his farm in order to have shelter and food, about how they did it all themselves, but they thank God for it just the same.

The Civil War rages around his farm, but he stays out of it. He has no love for slavery, but he’s not willing to fight to end it. He has no problem if his daughter marries a Confederate soldier. He lets his sons make up their own minds on whether or not they want to fight for the Confederates. He is the original libertarian. It is difficult to watch a film like this in times like these and not feel at least a little bit of animosity towards him. The film takes some pains to show that he is against slavery, but also against the war in general (which is why he isn’t fighting for the North) but it still feels like a cop-out. When your neighbors are literally fighting for their right to own slaves, it is hard to make a case for just staying neutral. That makes it hard to like the character. And he is clearly supposed to be likable.

But I’m digging too far into the weeds. James Stewart is such a warm actor it is hard to not automatically love any character he’s playing. Charlie Anderson is a man who just wants to raise his family and live his life. The film is a good one even if I have trouble with the way it washes over some of the more troubling aspects of the main character’s outlook.

The family is eventually drawn into the war when the youngest son (called simply “Boy” and played by Phillip Alford) is captured by Union soldiers. He’s captured because he’s out running around while wearing a Confederate soldier’s hat. It is a hat he found floating down a stream. A hat he’s worn around his father who seems perfectly okay with that fact. A hat that symbolizes the right to own slaves. And here I go again. I liked so much about this film. It is beautifully shot and wonderfully acted. The story is funny with some good action scenes. I quite enjoyed watching it. And while it is never pro-slavery, there isn’t anyone who ever argues for owning slaves, it never bothers to indicate just how awful that institution really was. It is hard to root for a film that just sort-of shrugs about an absolute evil.

Another example: The family learns that there is a train full of Confederate prisoners and that Boy might be on it. They set up a road block and stop the train. When Boy is not found, they free all of the soldiers and burn the train. The film indicates that the war is just about over by this point and there is no real way the Confederates will win. It also shows the Confederate prisoners to be exhausted and indicates that they will go home rather than keep fighting. But it’s hard to believe that all of them would. Surely, some would meet up with the army and fight some more. Prolonging the war. Ending more lives.

One more: early in the film, we see a young black child playing with Boy. The two are seen as friends though the child is clearly a slave. They are playing together when Boy is captured by the Union soldiers. One of those men says to the child that he is free. Later at the Anderson farm, he indicates that his master has been gone a long time fighting in the war and that his family is all dead. He is told once again that he is free. He walks down the road to rousing music as if everything is just fine. But I couldn’t help thinking a young black boy walking north would likely be caught and beaten or killed as a runaway.

In fact, we do see him later fighting for the Union. He nearly kills Boy but saves his life at the last minute when he realizes it is his friend. Boy, you see, has escaped from the Union soldiers with a group of Confederates. On their way South, they run into a skirmish and fight. Boy is fighting for the Confederates. His friend, a former slave, saves his life. It is meant as a meaningful moment. A former slave fighting for the North and a white boy fighting for the South find common ground. But I couldn’t help but wonder about the emotions that go unspoken. What does this black child think about his friend literally fighting for the side that wants to enslave him? But the film isn’t interested in such nuance.

Which is perhaps a sign of the times it was made in. In 1965, the country was still very divided. The Civil Rights Act was just a few years old; Martin Luther King, Jr. had just marched on Washington a little over a year before. Those Civil War monuments we keep arguing over and taking down were still relatively new. The Vietnam War was raging. One could argue this film is a metaphor for Vietnam. In that light, Charlie’s indifference is perhaps less difficult to accept. My point is that an audience watching Shenandoah in 1965 would likely have a much different point of view about Charlie’s stance than I do in 2021.

Reading reviews on Letterboxd from recent times and it is easy to find folks enjoying the film on its own terms and not grappling with these questions that I can’t seem to let go of. And that’s fine. As I’ve said, it is a well-made and enjoyable film. If you can turn off questions about standing idly by while a war over slavery is fought, then I suspect you will enjoy this film a lot more than I did. There were moments I was swept up into the film and those questions left my mind as well. But then they came back and I struggled with it once again.

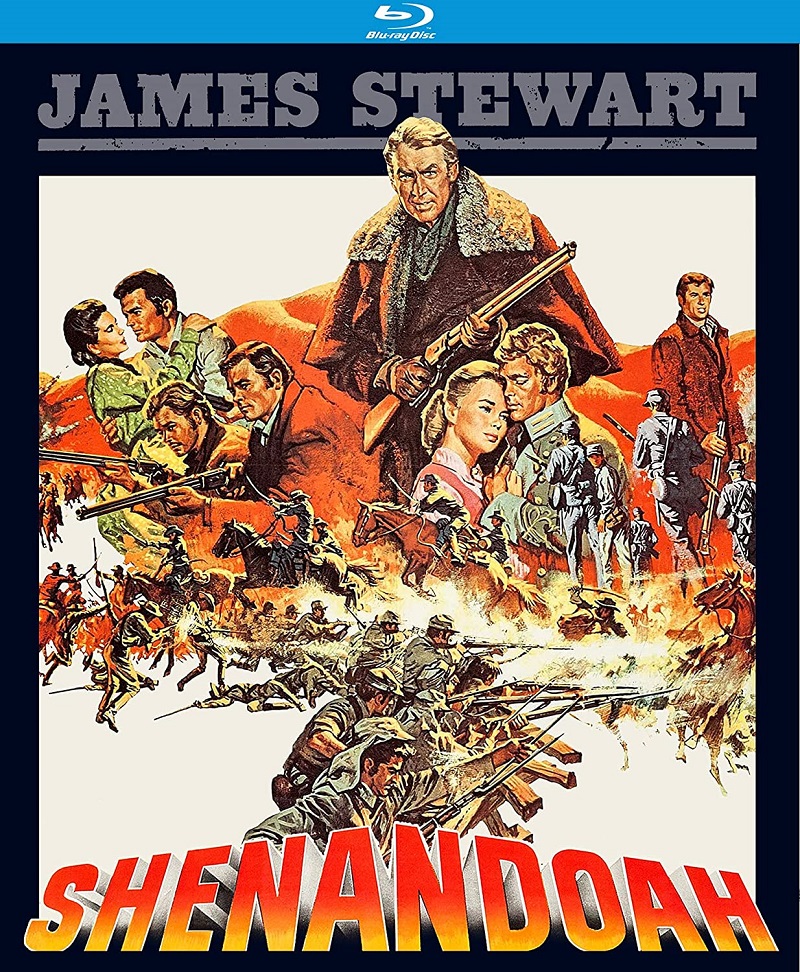

Kino Lorber presents Shenendoah with a nice-looking 1080p transfer. Extras include an audio commentary from film historians Michael F. Blake, C. Courtney Joyner, and Constantine Nasr plus some trailers for other Kino Lorber films.