In several respects, the release of Woody Allen’s A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy in 1982 marked the beginning of two pivotal points in the career of Woody Allen. Not only was it the year he began releasing a new motion picture each and every year ‒ a tradition (or obsession, perhaps) that continues to this day ‒ but it was also his first film with Orion Pictures, a company with which he would find backing and distribution for his next eleven projects. It was during his Orion constellation that Allen made a number of homages to classic film genres (and even the golden age of radio) ‒ a motion in pictures he had previously visited with Love and Death for United Artists in 1975.

Shadows and Fog (1991) ‒ an homage to German Expressionist cinema, with nightmarish nods to Franz Kafka and the even more unearthly tones of paranoiac politics (see: Donald Trump) is also a pivotal point in the hard-working filmmaker’s career. It was not only Allen’s most expensive association with Orion, but his last: the film would barely earn less than a fourth of its reported budget back at the box office; Orion itself soon began the proceedings for its infamous bankruptcy in the middle of the decade. Secondly, it would prove to be all but the end of Allen’s series of homages to movie styles most contemporary audiences knew little to nothing about (an ignorance that would only grow with the birth of subsequent generations).

Lastly ‒ and this is perhaps the most important aspect of the three ‒ Shadows and Fog marked the beginning of Allen’s decline in American cinema; the bulk of his preceding output going largely unnoticed or flat-out ignored (certain media scandals notwithstanding) by moviegoers, especially once his association with Miramax Films started (wherein he brought us movies like Celebrity and Everyone Says I Love You, where actors such as Edward Norton and Julia Roberts broke out in song, despite not having singing voices). It’s not as if he wasn’t trying, either. Heck, if anything, it became a case of a man becoming so completely absorbed in his own work, he focused more on quantity rather than quality.

And this is all coming from a moderate fan of Woody Allen’s movies, mind you. Although I will never forgive him for Everyone Says I Love You.

Set in a very 1920s Eastern European-like setting, Shadows and Fog opens with a wormy Woody being aroused from a deep sleep (OK, maybe I shouldn’t phrase it like that) by a vigilante mob determined to catch a deranged serial killer who is very much at large. Meanwhile, circus sword-swallower Mia Farrow leaves her cheating clown of a boyfriend (John Malkovich) and wanders out into the foggy night full of murderers and mobs. Eventually, Allen and Farrow cross paths ‒ just as everyone else in the story crosses paths ‒ and form a wit-strewn alliance into commentaries on every aspect of society. But mostly sex and death, since this is a Woody Allen film (it comes as little surprise that it was based on his own one-act play entitled Death).

Aesthetically, there is no denying Shadows and Fog of its art. Filmed on a vast 26,000-square-foot set in New York’s Kaufman Astoria Studios ‒ the largest set ever built there, for the record ‒ every inch of Allen’s cobblestone world is as believable to its audience as its shaded corners are deadly to its inhabitants. Nor can you dismiss Allen’s supporting cast: John Cusack, Madonna, David Ogden Stiers, Fred Gwynne, Kate Nelligan (who gets nothing but long shots), Wallace Shawn, Kenneth Mars, cult favorite Donald Pleasence (making this the closest thing Woody Allen ever came to making a horror movie, save for Everyone Says I Love You, of course), and Kathy Bates, Lily Tomlin, and Jodie Foster as prostitutes.

Alas, it’s just not enough (a scene with Ms. Foster in bed with our story’s auteur may warrant one to shield their eyes, as well). Despite all the jokes (many of which aren’t as “funny” as they should be), the engulfing style, the cameos by well-known names of the time and guest appearances by as-yet-unknown performers like William H. Macy and John C. Reilly, Shadows and Fog amount to being little more than a classic example of “smoke and mirrors.” Quite literally in the instance of the film’s finale, wherein the captured killers vanishes, no justice is served, and our characters ‒ as if they have become self-aware ‒ carry on with nary a care in the whole wide 26,000-square-foot world. The film’s message: “Escape reality, and live in a dream.”

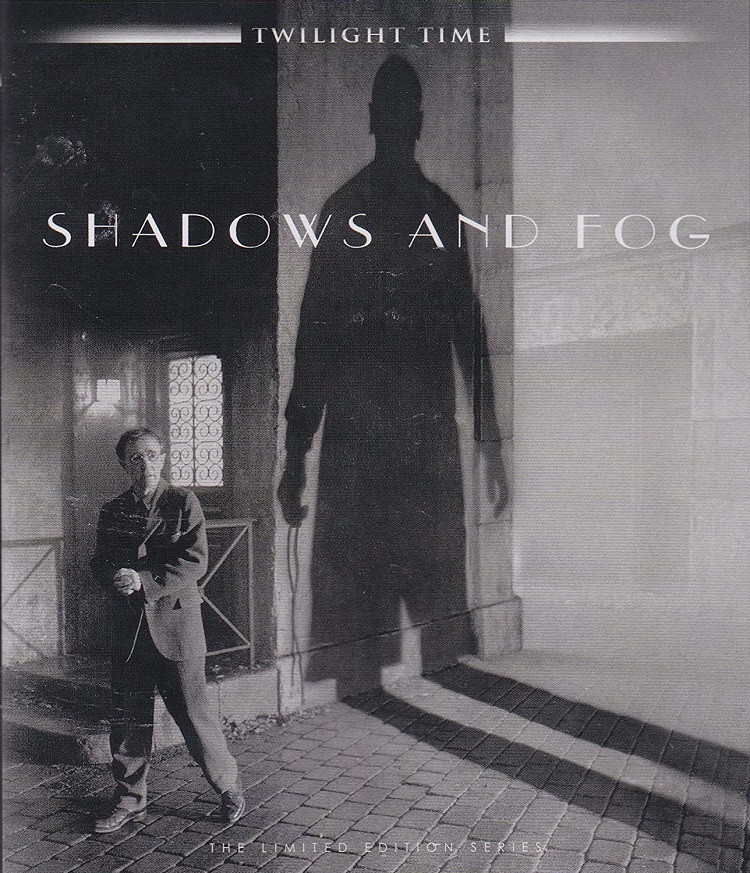

Though disappointing on several levels, Shadows and Fog still warrants a good viewing or two from Woody Allen’s faithful flock, people who like their movies to be categorically unusual, or anyone who can appreciate a filmmaker’s own appreciations to the cinematic worlds of yesteryear. And there is no better way to see this story than via Twilight Time’s 1080p Blu-ray presentation, which preserves the atmospheric black-and-white film’s 1.85:1 theatrical aspect ratio with a DTS-HD MA 1.0 audio track and (SDH) English subtitles included. Special features for this release are limited, with a DTS-HD MA 2.0 isolated score, an original (open matte) theatrical trailer, and well-researched liner notes by Twilight Time’s Julie Kirgo in accompaniment.

The Bottom Line: At least it’s loads better than Everyone Says I Love You, so do with that what you will.