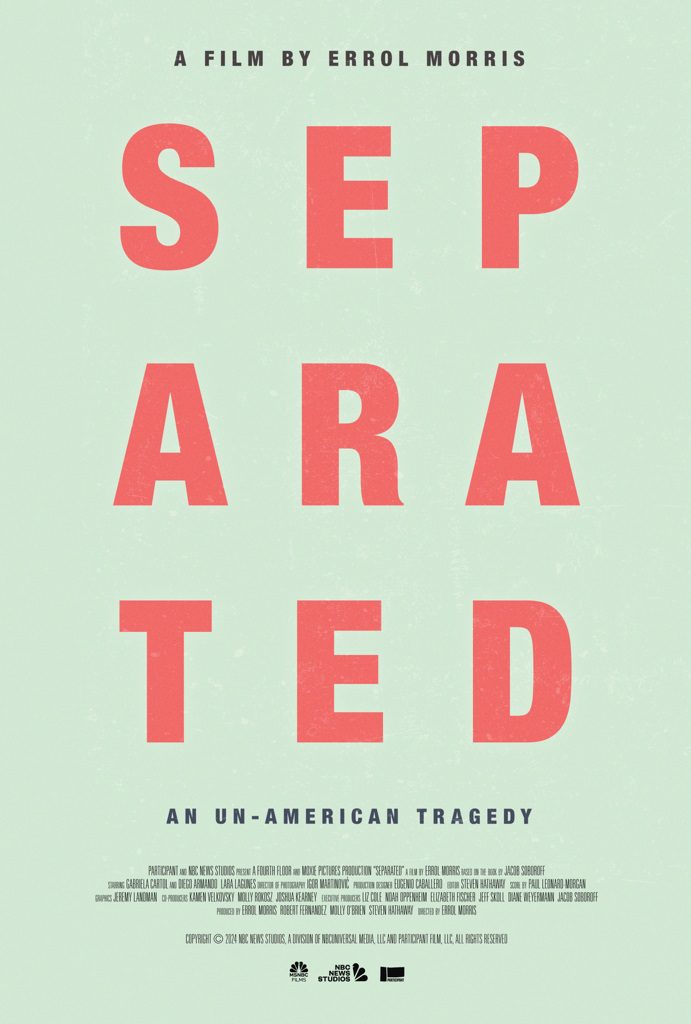

Errol Morris continues his streak of astonishingly edge-of-your-seat storytelling and filmmaking in his latest documentary, Separated, based on the book by NBC journalist Jacob Soboroff. This time around, Morris shines his light on flawed government policies unique to the United States: First, the policy of Catch and Release, in which immigrants crossing the border were allowed to begin the immigration process and then were released into the interior of the country while they waited for their immigration hearing; and the second policy, instituted by President Trump’s administration when first taking office, in which children were separated from their parents as soon as they were caught at the border. The policy was meant to deter parents from coming to the United States for fear of being separated from their children.

Buy Separated: Inside an American Tragedy paperbackMorris utilizes three main techniques to tell the story. First, there is a movie within the movie about a single mother (Gabriella Cartol) and her young son (Diego Armando Lara Lagunes) attempting to cross the U.S. – Mexico border from parts further south. The mother is strong-willed and filled with love for her son whom she hopes will have a better future in America. Her son, however, looks rather perplexed by the entire process and blames his mother, whom, unable to understand the complexities of the situation, Diego believes left him at the border to fend for himself. The story is engrossing and heartbreaking and a reminder that Morris could spend his time directing anything, including fictional films.

The second storytelling technique introduces actual emails and documents concerned with the policy of family separation at the border. Utilizing a sort of address book on the left side of the screen helps to keep the different players organized in your head. Large groups of people were involved, and a lot of communication was created. Morris does an outstanding job of parsing these complex documents to help tell his story.

The third technique is interviews with the players who were willing to speak to the topic. Morris uses his personal invention, the Interrotron, which allows interviewees to look directly into the camera instead of distractingly off to the side. This creates a sense of being a part of the conversation for the viewer, and it somehow adds tension to every scene. Morris is able to get people to talk and not only interviews those who were unwilling participants in the planned separations, but a few moments of insight come from those who were, in subtle and overt ways, responsible for the policy.

Especially interesting are interviews with Captain Jonathon White, Deputy Director in the Office of Refugee Resettlement, who claims that “harm to the children was part of the point.” Then there is the deer-in-the-headlights interview with Captain White’s boss, the Director of the Office of Refugee Resettlement, who seems to believe he was just doing his job and doesn’t appear to understand any of the damage done to children ripped from their parents at the Southern border.

Highly recommended.