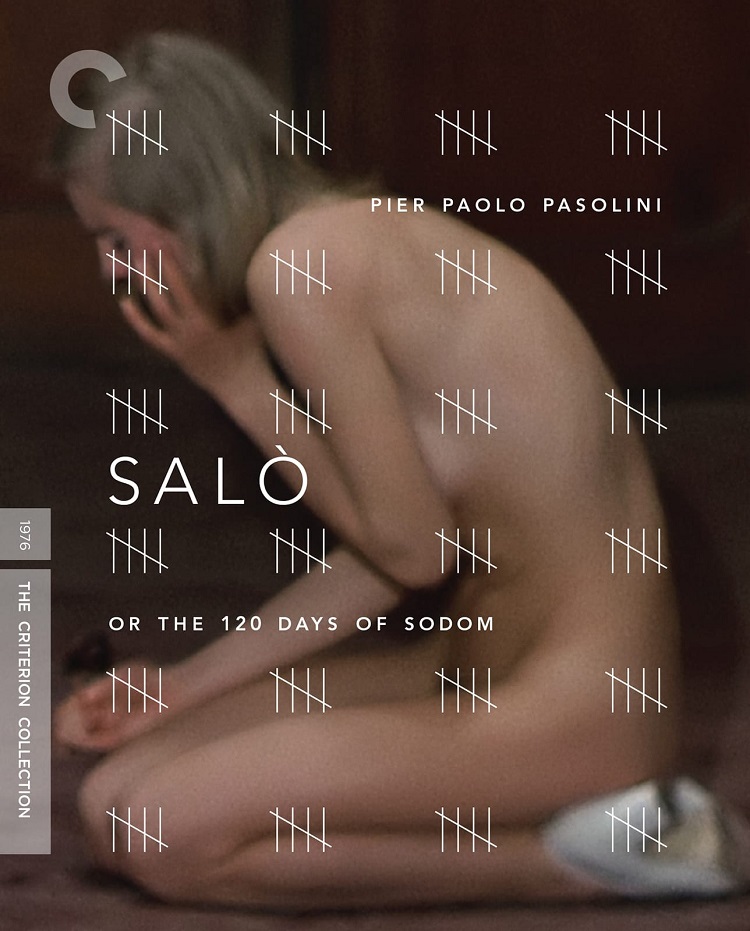

Salò is the most repulsive film I have ever seen. So much so that I completely understand the censorship it continues to run into. After watching the extras, I understand that may well have been director Pier Paolo Pasolini’s purpose as he used this adaptation of the Marquis de Sade’s The 120 Days of Sodom to comment on society, such as denouncing fascism and consumerism, but surely he could have found some other way, a better way, to get his point of view across because his execution is so vile it’s extremely hard to see anything beyond the surface of what transpires.

Sade’s story is transported from 18th century France to the Republic of Salò of Northern Italy circa 1944-45, during the last days of Nazi-Fascist occupation under Mussolini. Titles reveal Pasolini is about to take the characters and viewers through Hell like Dante’s Inferno. In the “Antechamber of Hell” segment, four leaders of the terroritory (the Duke, the Bishop, the Magistrate, and the President) with the help of young armed thugs and older prostitutes are inexplicably able to kidnap local children. The men then have the children paraded naked in front of them and choose 18, nine of each sex, to come away with all of them for four months of utter depravity.

Chapter titles describe the levels of Hell about to be endured. They are Circle of Obsessions, Circle of Shit, and Circle of Blood. Each gets progressively worse for the children and the viewer. The prostitutes tell stories of disgusting acts they allegedly experienced, which somehow turn the four men on. Under armed guard, the children are tortured and humiliated. The men even take turns with each other. During the Circle of Shit, everyone eats feces. The film concludes with Circle of Blood, which finds the male leaders made up and wearing dresses. They then take turns watching from afar as the others maim and kill the children.

While I know throughout time there have been and continue to be stories of people who have stood by and watched others receive brutal treatment, it’s very hard to accept in a story without presenting the mindset of those characters and offering some insight. Even the victims barely resist and accept their fate, which is also difficult to believe considering what they go through. I would expect either more of an uprising or at least an attempt as opposed to what is presented. The minor bits of rebellion aren’t enough.

The video was given a 1080p/MPEG-4 AVC encoded transfer displayed at an aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The liner notes reveal, “This high-definition digital transfer was created on a Spirit 2K Datacine from a 35mm interpositive. Thousands of instances of dirt, debris, scratches, splices, warps, jitter, and flicker were manually removed using MTI’s DRS system and Pixel Farm’s PFClean system, while Digital Vision’s DVNR system was used for small dirt, grain, and noise reduction.” With that, there is still some bits of noticeable dirt and scratches. The colors appear in dull hues and are consistent. Film grain is present, but not distracting. The detail reveals defined textures, though there is some slight alaiasing from the tweed clothing. The audio is LPCM Mono and English Dolby Digital Mono. The liner notes also state, “The original monaural soundtrack was mastered at 24-bit from a 35 mm magnetic track. Clicks, humps, hiss, and hum were manually removed using Pro Tools HD. Crackle was attenuated using AudioCube’s integrated workstation.” I only listened to the Italian. Ennio Morricone’s score is balanced well with the dialogue. The gunfire comes with little bass to make it sound real.

Pasolini was murdered under questionable circumstances before Salò’s release so he was unable to defend the film against critics, but the supporters presented here fail to make their case. In the 2001 documentary “Fade to Black” (1080i, 24 min) director Catherine Breillat makes the bizarre claim that Salò is “one of the most important movies of the world” and that “it’s shocking because it’s not meant to shock.” David Forgacs, Professor of Italian at University College London, disagrees with those who claim the film is pornographic “because it’s unpleasurable” yet under the definitions of “pornographic” one meaning is “the depiction of acts in a sensational manner so as to arouse a quick intense emotional reaction.” I can’t imagine anyone believing Salò doesn’t meet that definition.

All the other features are also presented in 1080i. “Salò: Yesterday and Today” (33 min) presents interviews with actors Helene Surgere and Ninetto Davoli as well as archival footage with Pasolini, who comes across like an intelligent man, so it’s hard to believe he failed so miserably here. But it seems he liked his ideas so much he couldn’t view what he was doing objectively. There is also footage of him directing on the set during the final day of shooting. “The End of Salò” (40 min) presents cast and crew members talking about the film and its director. Participants include actors Antinisca Nemour and Paolo Bonacelli, screenwriter Pupi Avati, production designer Dante Ferretti, assistant director Fiorella Infascelli, and assistant editor Ugo Maria De Rossi. Production designer “Dante Ferretti” (11 min) talks about his working relationship with Pasolini and specifically Salò, their fourth film together. Filmmaker “Jean-Pierre Gorin” (27 min) also weighs in. There an English-language trailer (4 min) and an 80-page booklet featuring essays by Neil Bartlett, Catherine Breillat, Naomi Greene, Sam Rohdie, Roberto Chiesi, and Gary Indiana, as well as excerpts from Gideon Bachmann’s on-set diary.

Forget recommend; I would discourage everyone from seeing Salò, even on a dare. Other artists have dealt with these issues and ideas in much more palatable ways.