Written by Kristen Lopez

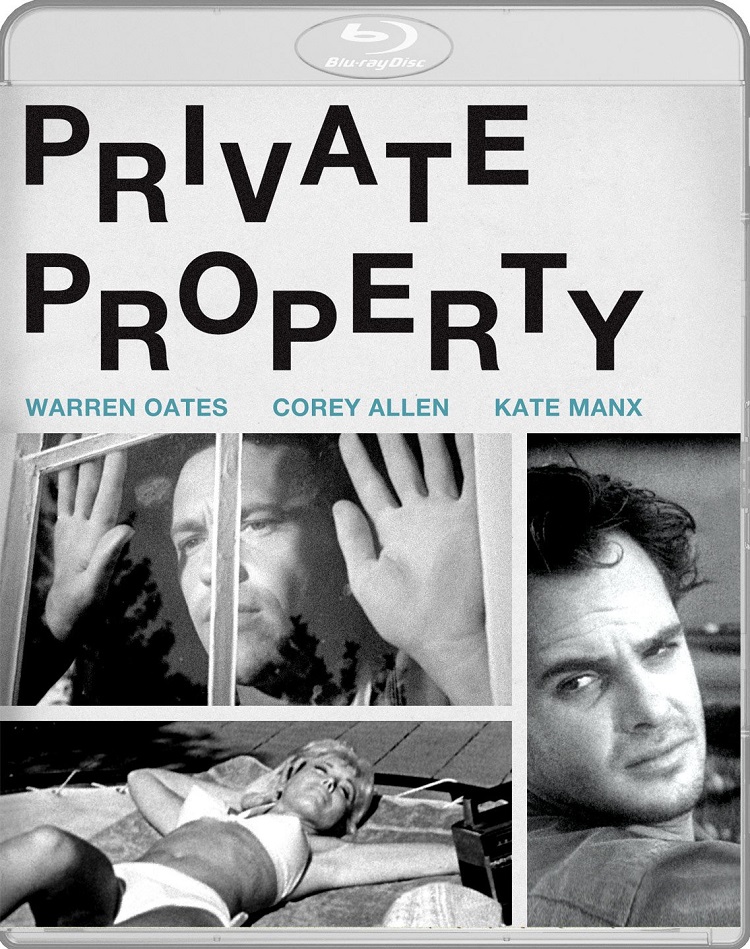

It’s an average day in sunny Los Angeles. Two men – you wouldn’t immediately avoid them but they definitely possess an agenda – come out of the haze with crime on their mind. So begins Leslie Stevens’ little seen noir, Private Property. The low-budget film, shot in ten days, recently premiered at the 2016 TCM Classic Film Festival, bringing to light a twisted, sexually charged noir that ties in to today’s gender dynamics.

Duke and Boots (Corey Allen and Warren Oates) are two small-time hoods. Boots is a virgin intent on proving his virility to Duke, and a random encounter with the beautiful Ann (Kate Manx) marks her as the perfect person for Boots to “make it” with. The two follow Ann home and Duke starts to ingratiate himself with the lonely housewife, but is he doing it for his friend or his own selfish purposes?

Private Property has that early 1960s independent gauze over it, reminiscent of Carnival of Souls, an interesting comparison as both deal with women in unique situations with men and male dominance. This was Leslie Stevens’ directorial debut, and he’d find greater success in television, but he has a deft control over how the film plays out.

Why this wasn’t widely released is easily observable from the minute Duke questions if Boots is saving himself “for a rich daddy.” Sex, who’s getting it and who isn’t, is the sun the plot revolves around and the script doesn’t hide the fact that the sexual tension between the characters boils hotter than the Los Angeles sunshine. Boots and Duke are two men on opposite ends of the masculine spectrum, and each has something to prove about what it means to be a man today. A veneer of black humor runs throughout; they force a man to drive them somewhere and threaten his life, only to worry whether “he makes it over the hill” after dropping them off.

The two are determined to have sex with Ann, but they draw the line at outright rape (what gentlemen!), instead taking an approach akin to “rough wooing” by getting close to Ann through friendship. Duke gives Boots tips on how to “read the signs” that indicate if a woman is interested in you, and what’s horrifying is how the two men interpret said “signs.” Duke and Boots’ relationship is not that different from George and Lenny in Of Mice and Men; one is the confident leader to the more simple-minded follower. Allen lives up to the name Duke, a swaggering master manipulator who presents himself to Ann as an “aw, shucks” blue-collar working man trying to make good. Oates’ Boots is literally hidden in shadow, left alone in the house across the street as Duke does his wooing for him akin to a gritty Cyrano. When things come to their inevitable climax, it is Duke who ends up the more monstrous of the two in a simpler, more insidious way.

Allen and Oates’ unpredictable thugs are the ones we meet first, our protagonists so to speak, but Ann is more mysterious. Played by Stevens’ then wife, Kate Manx is the poster child of the California girl and housewife. We’re privy to Duke and Boots’ thoughts about Ann, the camera leering through Venetian blinds to give us the men’s point-of-view. The men’s obsession with the cool blonde is near-Hitchcockian and Duke’s name-drop of the director while pretending to look for an address is an intentional call-back.

Ann’s marriage to a man significantly older than her is fraught with problems. He believes buying her a car and giving her a nice house is enough to satisfy her, and Ann spends her days between swimming in the pool and her kitchen. Treated like a little girl by her husband, listening at his feet as he describes his day, it’s no surprise that Ann is desperate for male attention, especially sex; many scenes have her lounging on her back or placed in other vaguely sexual positions, tricking both the audience into questioning its intent and placing Ann in the position of instigator to her own pleasure. Duke’s arrival fans the flames of her simmering passions, leading to a multitude of associations with the title “private property” that’s both feminist and misogynist.

The new 4K restoration, mostly recently screened at TCM, looks fantastic. Because this is a low-budget film it’s remarkable how little grain is shown, and how the haze is brilliantly rendered.

Private Property marks Hollywood’s entry into the dark and gritty realism that would come to encapsulate the decade. With the rise of Vietnam questions revolving are masculinity are asked, as well as what defines private property in a marriage or relationship, things the Hollywood dream factory wasn’t even thinking to ask. This is a hidden gem that’s a welcome addition into the pantheon of independent cinema.