As one of those individuals that became the slightly pretentious artsy-fartsy feller during his teenage years whilst growing up in a small town, I frequently made trips to video stores (or at least ordered random titles from grey market mail-in video distributors) in search of something that I surely thought would add a little culture to my mundane, tormented existence. It was through these actions that I transitioned from one phase to another – discovering and subsequently learning to appreciate the work of oft-renowned filmmakers such as French New Wave pioneer Jean-Luc Godard, the stylish bullet ballet work of Hong Kong’s John Woo, and the gory Italian splatter flicks of one Lucio Fulci.

At one point, my preference was the French period of surrealistic filmmaking by Spanish director Luis Buñuel. This later turned into a fascination for other free-flowing and strangeness in general that eventually resulted in my first encounter with openly gay Marxist filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini. The film in question was 1968’s Teorema, and the print used in the videocassette I sat up one night and viewed was about as clear as a recently disturbed mud puddle. So was the content of the film itself, I thought. Frankly, I remember very little about the movie to this day – save for a scene where a young painter urinated on his own artwork – something that was, without a doubt, supposed to convey a message to me and my ostentatious attitude on life. It didn’t, however. Instead, I went on with my mundane, tormented existence feeling Pasolini had done the exact same thing to me.

Here I am now, a couple of decades down the line, and it has come time for me to face-off with Signori Pasolini once again. Fortunately, during the years between the so-existential-it-hurts Teorema and his final film – the highly controversial de Sade adaptation, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom from 1975 (in which far more unsettling imagery than a lad’s quick relief on canvas takes place; the filmmaker in question was murdered under still-mysterious circumstances shortly after completing the film, as well) – Pasolini decided to look on the brighter side of life. Instead of penning his own grandiose views on time and being (as only he could), he chose to adapt the works of other, less-showy [actual] authors.

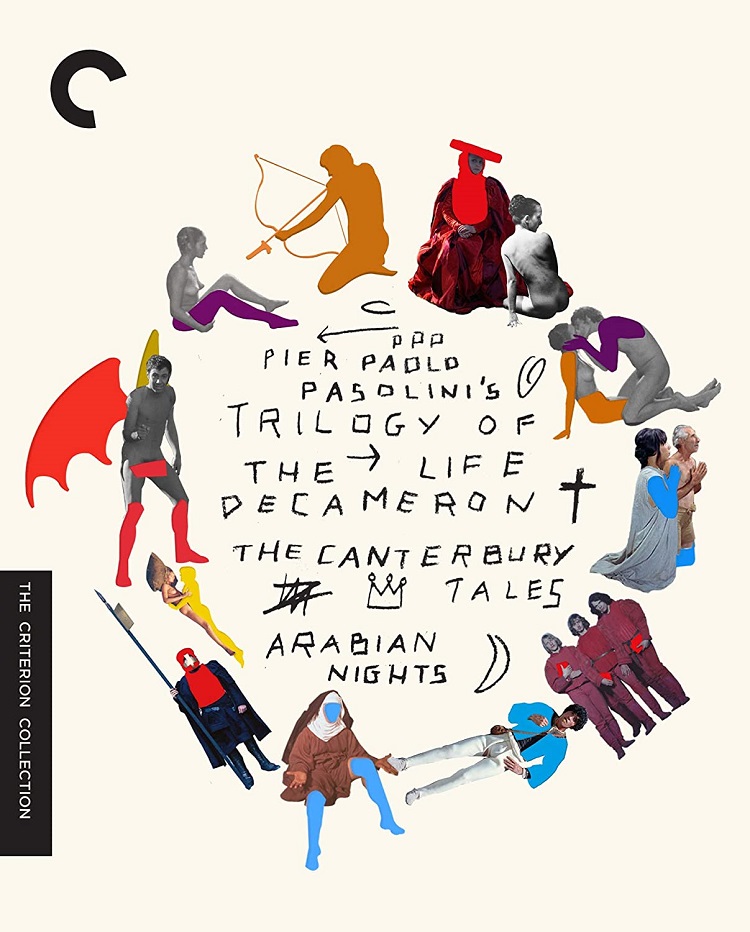

Thus, the Trilogy of Life was beget in 1971 with The Decameron (Il Decameron). Somewhat freely adapted from the novel by Giovanni Boccaccio, the tale consists of nine unrelated vignettes (as opposed to the 100 in the original literary source) that are vaguely connected in one way or another, and which feature a score by famed composer Ennio Morricone. Seduction, swindling, and such familiar facets of life such as waiting for inspiration and the contemplation of what lies beyond death are touched upon here. Granted, Pasolini still indulges in scatological humor (at least it’s humorous here – see Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom) and nudity and sex abound as usual, but the general atmosphere Pasolini paints in this instance is considerably happier in nature – and nowhere near as self-absorbed as a majority of his other work. Franco Citti, Ninetto Davoil, and Angela Luce represent some of the more familiar faces in this work that won itself a special Jury Prize at the 21st Berlin International Film Festival.

Have you chimed in on the fact that I’m not a huge Pasolini fan yet? Just wondering. Moving on, children, we find ourselves at 1972’s The Canterbury Tales (I Racconti di Canterbury), wherein our writer/director takes eight of the 24 stories featured in the original Geoffrey Chaucer work and adds his own special touch to the fray. Here, we witness the Devil coming to revel in mankind’s misery, a young bride conspiring against her older hubby so that she can be with her younger lover, a bizarre homage to Charlie Chaplins’s character of the Little Tramp, and – towards the film’s finale – Pasolini employs the usage of a huge ass that is literally of The Devil secreting bad priests unto the world. It’s humorous, so I’m told. Morricone again provides the score, with performers such as Hugh Griffith, Laura Betti, Franco Citti, and Josephine Chaplin (Charlie’s daughter) appearing in this production. This one won an award at the Berlin International Film Festival, too – during the annual venue’s 22nd year.

Finally in this seemingly-misnamed trilogy, we have Arabian Nights (Il Fiore Delle Mille e Una Notte) from 1974, which takes on the classic Arabian text, The Book of One Thousand and One Nights. Rather than make the effort of adapting the source material this time ’round, however, Pasolini just kinda does his own thing – with a slave girl (Ines Pellegrini) being sold to her future lover (Franco Merli), who somehow manages to lose her later. Thus, he sets out to find her – encountering several weird stories involving several even weirder people. As a lad who grew up filtering through his father’s old Playboy magazines, I vividly remember seeing a number of stills from this movie in the famous publication. While it was nice to finally associate those images with its original narrative, I can’t say there’s much of a narrative to rely on. Franco Citti appears in this one, too, and Ennio Morricone supplies the music once more. Arabian Nights managed to take home a special prize at Cannes. A longer cut of the film was reportedly lost.

Interestingly enough, shortly after completing his work, Pasolini rejected his own Trilogy of Life – feeling that he had become too commercial or perhaps laissez-faire (or whatever the Italian variation of such a phrase is) – and who probably felt he had gone against his so-called Marxist ways (the fact that he owned a castle near Rome never bothered him, I guess!). Naturally, the Trilogy of Life has gone on to be his more acclaimed (not to mention mainstream) work with the masses – who seem to be able to handle his tendency to contruct movies around sex, slapstick, nudity, and scatological humor in smaller doses. Can’t imagine why.

The Criterion Collection went all-out in order to restore and present the Trilogy of Life to DVD (and Blu-ray). And, while the series will never succeed in being a personal favorite of mine, they definitely did a great job. Accompanying each film is an Italian-language monaural soundtrack with removable English subtitles. On an interesting note, The Canterbury Tales features an alternate English-dubbed soundtrack (that Pasolini himself supervised). It’s rare that Criterion includes such alternate audio tracks (as most cinema snobs feel dubbing is of the Devil), but it’s a welcomed addition nonetheless. Frankly, I’d like to see more foreign-language flicks from them with English audio: it sometimes adds (though not always flatteringly) to the surrealistic enjoyment of an already strange flick.

Special features for this set vary from title to title. There are interviews with scholars and filmmakers from both the past and present, documentaries/essays for each film, reconstructed deleted scenes from the third title, and several trailers. A rather well-stocked booklet is also included in the set – which includes Pasolini’s written rejection of his own work, so you can judge for yourself whether the guy was bipolar like I firmly believe he was.

In short: make mine Buñuel.