The first film in Austrian director Ulrich Seidl’s Paradise trilogy is the fascinating and troubling Paradise: Love. Initially, Seidl had intended on shooting Paradise as one complete picture. But after four years and over 80 hours of rushes, the only decision that made sense was to split it into three features about three women from one family.

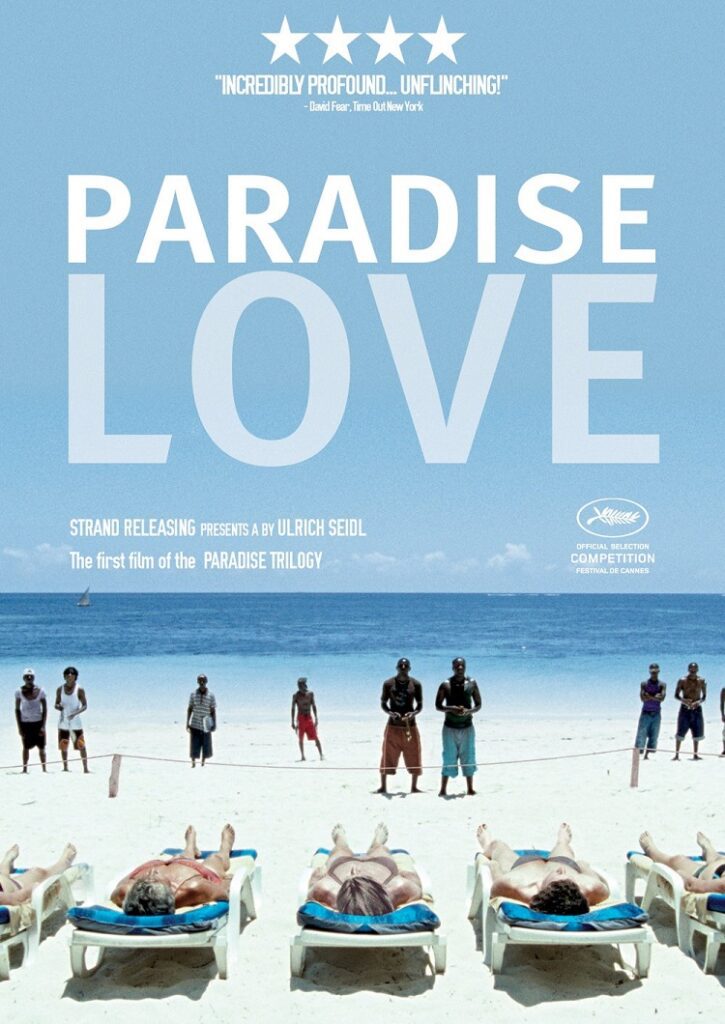

Paradise: Love deals with sex tourism in Kenya. The trilogy also includes Paradise: Faith and Paradise: Hope, respectively dealing with a Catholic missionary and a diet camp. For this picture, Seidl’s “paradise” is barren; his view is of a culture of necessary exploitation.

Margarethe Tiesel is Teresa, a 50-year-old woman in need of an escape. She leaves her daughter with her sister and heads off to Kenya for a vacation. She is eventually swept up in the idea of being a “Sugar Mama,” a sex tourist with a thirst for the “Beach Boys” lingering outside the roped-off range of her resort.

Thanks to the encouragement of a friend (Inge Maux), Teresa moves from one African man to the next. Munga (Peter Kuzungu) seems to be authentically in love with her, but the real story is more “complicated.” Teresa longs for someone to look her in the eyes, but the search is nearly impossible in a land where money is all that matters.

Paradise: Love is powerful because it focuses on a group of well-heeled women who are in love with the idea of being loved. They’ve come to a place where they believe they have control. They yearn to feel special and to feel young again, but the harsh realities of the Sugar Mama society sink in and the inevitable crush of disappointment takes its toll.

The Africa of Paradise: Love rings with the catchphrase “hakuna matata,” but this is no sanitized Lion King dance. This is a continent long victimized and it has become a den of exploitation in its own right. The Beach Boys have learned how to operate and how to turn tourists yearning for “the wild side” into opportunities.

This is a picture about being used. There’s an acknowledgement and an eventual acceptance of this fact, but that doesn’t stop Teresa from feeling the same dissatisfaction in Kenya that drove her to the locale in the first place. From the perspective of the “Beach Boys,” the acceptance of being used is part of the lifestyle. There is no shame; even wives are in on the operation.

Seidl’s steadfast working method is all over Paradise: Love. The filmmaker works from what could be described as a documentary setting and most of the picture is very organic. This is largely because of the lack of traditional script and any structured dialogue. And by using actors and non-actors alike, Seidl preserves authenticity.

Of course, it helps to have such skilled performers as Tiesel inhabiting key roles. Her Teresa is a figure of loneliness. Her struggle for contentment is neatly juxtaposed against her desire to feel loved. An early scene involving her life with developmentally-disabled adults suggests a tone of responsibility, as does an early scene with her daughter. Her desire to escape is apparent.

Paradise: Love is a hopeless motion picture. It reveals a Kenya where money is the only thing that matters. There are few redeemable characters among the “Beach Boys,” even if their actions are understandable, but the white women are far from innocent victims. This is equal opportunity exploitation: everyone gets what they’re after and nobody is truly fulfilled.