Ulrich Seidl closes his Paradise trilogy with 2013’s Paradise: Hope, the most sensitive offering of the bunch. Following up the troubling yet beautiful Paradise: Love and the bleak but authentic Paradise: Faith, this entry concludes the Austrian director’s meditation on seeking fanciful versions of what the trilogy’s respective titles offer.

And so it comes to Hope, a matter that compelling encompasses Love and Faith in a way. It delves into the affections of a 13-year-old girl (Melanie Lenz) and explores her idealism in the framework of a “fat camp” and the mythical love of a much older man. It also navigates the necessarily awkward articulation of said idealism.

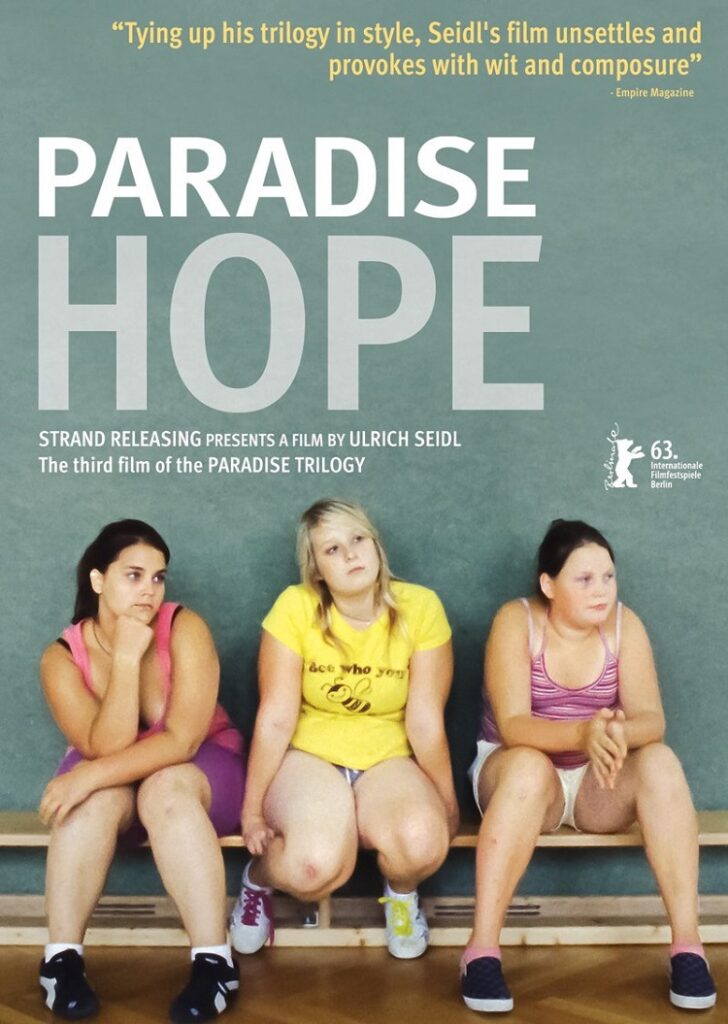

Lenz is Melanie, the daughter of Paradise: Love‘s Teresa (Margarethe Tiesel). She is sent to a “fat camp” while her mother vacations in Kenya and is dropped off by her aunt, Paradise: Faith‘s Anna Maria (Maria Hofstätter). Melanie discovers the camp to be a highly regimented facility, with organized meals and exercises. It’s more a military base than anything.

And yet she finds comfort and humour with the camp’s doctor (Joseph Lorenz), a 50-something who struggles with his own feelings in regard to Melanie. The girl falls in love, the doctor navigates his probing and inappropriate lust and very nearly crosses the line. Melanie describes her affection to her friends with expectant exuberance, but hopelessness abounds.

Through his trilogy, Seidl has adhered to his methodology. He has filmed in documentary settings and utilized unscripted guides with a cast of actors and non-actors. Case in point: Melanie Lenz, now a 16-year-old, is studying to work in retail sales.

This rudimentary sensibility gives her the innocent quality required to play her character. When she feels hurt, it’s authentic. When her eyes beam with love and possibility, it stings because Seidl constructs his universe with care and attention to detail. There is a sensitivity to Paradise: Hope that concludes the series beautifully.

This picture has notes of Nabokov’s Lolita, of course, but it also tilts the narrative by putting the focus on the girl. Her affection is pure, untainted by the suggestion of pedophilia in the doctor and unfettered by whatever expectations the world has. She doesn’t comprehend the irrationality of cozying up to a much older man.

That much older man is played with precision by Lorenz. Watch the way he encircles her and approaches her. Or consider how he lays her on the forest floor after she’s had too much to drink. His next movements are animalistic yet tender, the stuff of a predator assessing potential prey.

Seidl has the audience judge (or not judge) the circumstances. Between the scenes with Melli and the doctor, he includes disciplined, bellicose exercises where the kids in the camp trot around. Sound is used smartly, from the closing sequence of mealtime to a scene involving cross-country skis.

Paradise: Hope concludes Seidl’s trilogy with grace, displaying the filmmaker’s affection for his characters and the stories they tell. He has crafted a compelling set of motion pictures, a trilogy that focuses on the unwavering and pitiless nature of life and the incessant, yearning search for paradise.