As a director, Dennis Hopper used to strike me as a case study on how not to direct. His breakout success, Easy Rider (1969), caught my imagination early; and, under the fumes of its great rock music soundtrack, I took a shine to its arty fusion of the AIP biker film and the French New Wave. I don’t abhor it as some viewers do. Nowadays, though, I’m less sold on its myth, even if it helped usher in the last Golden Age of Hollywood. Still, if Easy Rider was a fluke, my saying so doesn’t (in my eyes) diminish Hopper’s talent. He was just, for my money, a better actor than a director (Blue Velvet [1986] showcases his best performance). On this topic, that could have been ‘all she wrote.’ Except… I watched his long-lost film, Out of the Blue (1980), earlier this month. It doesn’t exactly change my mind RE Hopper-as-director, but it proves that he did come back… if not all the way, at least some of the way… from his follow-up to Easy Rider, The Last Movie (1971), a shambolic, financial fiasco drubbed upon release, and which ran on the Criterion Channel a few months ago.

Often referred to as the punk son of Easy Rider, Out of the Blue wasn’t originally supposed to be a Hopper joint. After the producers fired the first writer-director, Hopper spent a weekend retooling the script so that it centered on Linda Manz, the genuine star of the show. It was a splendid choice. And if the movie isn’t an unmitigated triumph, (and its slightly unconventional look at alienation isn’t as poetic or, ahem, profound as I dare say Hopper hoped), it is even more of a bum trip than Easy Rider or The Last Movie was. It’s one that almost breaks your heart.

Meet Don (Hopper), a lush who, 15-year-old daughter CeBe (Manz) in tow, crashes into a school bus of kids dressed for Halloween. Five years pass. CeBe and her mom Kathy (Sharon Farrell, astounding), a floozy server in a restaurant with no customers, drift through life in the Pacific Northwest (it’s Vancouver, British Columbia, to be exact). Unsupervised, CeBe spends a lot of time wandering the city. She goes to bowling alleys and cowboy bars. She attends punk rock concerts. Occasionally, her teddy bear and a handheld tape player are with her. She’s a big Elvis fan, and she loves the Sex Pistols, whose lyrics she blasts out on the CB radio in her dad’s busted-up truck. CeBe is lost, or she’s on the edge. Either way, a court-appointed therapist (Raymond Burr [that’s right, Mr. Perry Mason himself]) assures Kathy, CeBe will get better once Don leaves the slammer. Once the family unit re-coheres, things will be fine again.

Wrong.

Don gets a job at a garbage heap, but he hasn’t reformed. He’s still an incorrigible drunk who hangs around shifty dudes, Charlie (Don Gordon, sleaze incarnate) in particular, who bring out Don’s worst. And he’s still a pariah—as witness the confrontation he has with the father of one kid he killed. As sad and repugnant as this behavior is, it wouldn’t mean as much to the film if it didn’t mean something to CeBe. She loves him, just like she admires the other false idols who share Don’s crippling habit of self-destruction. He’s doomed, her mom too. The whole family’s hopelessly doomed. None of them can act ‘straight’ for long; none of them are able to take control of their lives. They’re bound to their cycles of pain and self-victimization. What light is there, you may ask? None. Any party, any music or noise—it’s just a prelude to disaster, which CeBe courts until she goes “out of the blue and into the black.”

This a film that leans hard, and I mean hard, on improvisation. Long, panning takes allow the actors to develop stretched moments of tension, of character-shading banter, interactions that often straddle the line between parody and revelation. In one bit, Don pours a bottle of booze on himself and says, “I’m just a motherfucking asshole, MAN!” I laughed where no comedy was intended, but there’s something true about the scene, anyway. None of this is slick. Hopper’s technique, pinned to a tighter than tight budget, informs that as much as his decision to keep things bleak, to let the seams show on the places and faces he found while filming. It adds atmosphere, yet select items risk the spell the movie casts (cf. the bus full of dummies, the silhouette of the camera operator at a punk rock concert, and the occasional non-actor who looks into the camera on accident). It’s this strange walk-up to the land of the amateur, as though Hopper casually stumbled his way through each scene and trusted his gut about the footage he got, that makes Out of the Blue a more intriguing endeavor than it may otherwise have been. It’s a document, a time capsule as much as Easy Rider was, and that, along with Hopper’s approach, gives it a charge. The improvisational aspect had all the potential in the world to make Hopper and co. look like fools. That it doesn’t is a credit to the actors.

And we keep coming back to CeBe, the heart and soul of the film. We want to. Through some alchemical combination of their talents, Hopper and Manz turn CeBe into a believable teenage mess for whom we care. A sharper-edged Tatum O’Neal, Manz holds her own against the loony Hopper in every scene they share. There’s a natural affection between them; it radiates from the screen. When she follows a taxi driver to a flophouse and puffs up at his pad, (as, looking on, a prostitute proudly displays her nether regions), she curls up into a fetal ball and sucks her thumb. This could have felt cheap, even tawdry; but it doesn’t. It lands as true, and how Hopper lets these (and other) moments play out without judgment or explicitly telling us how to feel about them gives them power. Manz sells her role, and whatever was going on with Hopper at the time (it was well-documented he was out of control with his addictions to drug and drink) funneled into a deep sense of compassion for what CeBe experiences. Not all is joyless for her, either. In the middle of the film, as a slight reprieve, CeBe gets to sit in on drums for part of a concert by the Pointed Sticks, a real punk rock group. It’s an exciting moment for her, and it might be her last. Small but tough, wild yet still bearing the tender scars of incest and neglect, CeBe could be one of the most compelling teenagers in movie history. Once we reach the film’s violent conclusion, we’re sickened yet relieved. For her and ourselves.

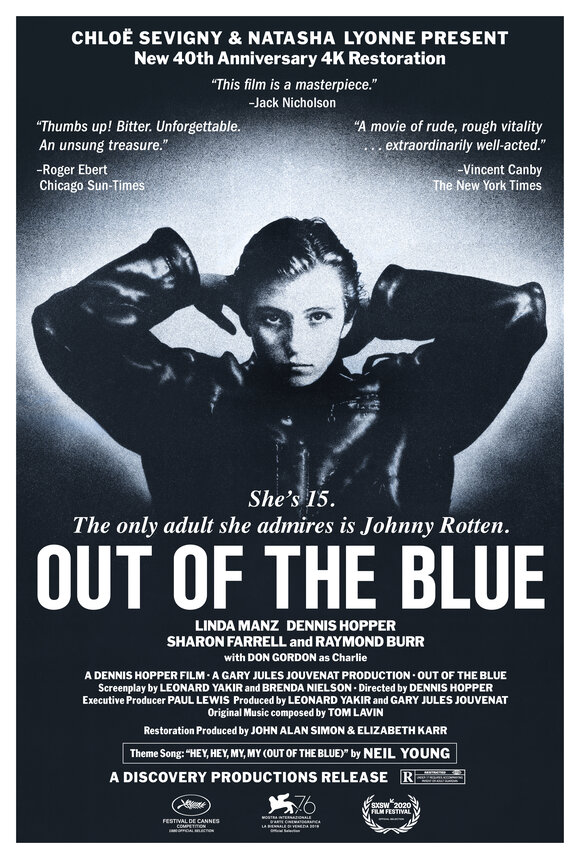

After Out of the Blue premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 1980, it didn’t receive a proper theatrical release until 1982, but even that was a limited run at select arthouses. The movie disappeared. Over time, though, its legend has grown. Many, as Hopper himself did, regard it as a masterpiece. Jack Nicholson included.

I’m on the fence, to be honest. The movie is the depressing, miserablist take on The 400 Blows (1959), with a punk rock edge, that we never realized we always wanted. And certainly, it could have been sappier. It could have been tamer, too, and more shock-for-shock’s-sake than it is. For every arresting moment or visual, though—for every punch it decidedly does not pull—it’s a mixed bag. Half the time, the movie hits hard. Otherwise, it comes off as rudderless, even boring. It’s as though Hopper took a bland after-school special and (in his spaced-out state) made it a hard ‘R’ examination, insisting on the bleakness of CeBe’s life as not just some affectation but as bitter truth, with the pervy, nasty habits and moments of confession on display stripped to their essence.

And yet… Out of the Blue sunk its claws into me for days, a feat that very few films manage. And I suppose that’s where I end this piece, appreciative that Hopper made an upsetting film about a troubled adolescent without ever getting corny or exploitive.

Or offering her a softer way out than the one through which she hurtles.

Discovery Productions restored Out of the Blue in 4K for its 40th anniversary. Presented by actors Chloe Sevigny and Natasha Lyonne, this re-release is in select theaters across North America. The run ends in mid-February 2022, but other dates and cities might be added. More information on the revival is available at the film’s website.