”Look at yourself in a mirror all your life and you will see Death at work,” says Heurtebise (Francois Perier) to Orpheus (Jean Marais) “like bees in a hive of glass.” It is a wonderful line, and one of Jean Cocteau’s main themes in his classic film Orpheus (1950). The statement also speaks to the character of Death (Maria Casares), who I feel is the true star of the movie.

In the most basic terms, Orpheus is Cocteau’s update of the classic Greek myth. In the tale, we find a musician so charismatic that his songs would charm any and all who heard them. When his wife Eurydice is taken by Death, Orpheus journeys to Hades to bring her back. The deal he strikes is that she will be allowed to return to life, on the condition that he not look at her again until they reach the land of the living again. The temptation proves too great however, and Orpheus loses her for eternity. He is then violently torn apart by the Furies.

In Cocteau’s re-telling of the story, Death is hopelessly in love with Orpheus. So much so that in the end she sacrifices her own deathly immortality to save him. From the moment we are introduced to her (initially as the Princess), Maria Casares commands the screen. She is both gorgeous and severe, portraying Death as the ultimate dominatrix. It is little wonder that Orpheus describes her as “burning like ice” during their final embrace.

The dream-state Cocteau intended is consciously spoken to throughout. During their first encounter, a seemingly annoyed Princess condescendingly snaps “Are you asleep?” at Orpheus. He often refers to being in need of sleep, although at one point he declares, “I’ve been resting on my laurels, I must wake up.” The unconscious is most vividly evoked during the trip into the Underworld. This is accomplished with one of Cocteau’s signature effects, by going through the mirror. Death’s chauffeur Heurtebise tells Orpheus that when he dons her gloves, the mirror will become like water, and he can slip right through. In some ways, this beautiful scene alone secured Jean Cocteau’s auteur status with the members of the French New Wave.

The space between the living and the dead is referred to as the Zone. The setting of the bombed-out Saint-Cyr military academy could not be more appropriate. Orpheus was filmed in France just four years after War War II ended. Audiences at the time must have immediately identified with the symbolism. It remains just as potent today.

When we first meet Death as the Princess, she is presented as something of a Left Bank cougar. This takes place at The Poets Cafe, described as “the center of the universe,” by the Editor (Henri Cremieux). She is accompanied by an 18-year old poet-named Cegeste (Edouard Dermithe), who has usurped Orpheus as the superstar of the poetry world. The situation neatly prefigures the emergence of Elvis, The Beatles, and those who would rule the pop firmament in the decades to come.

Cocteau’s brilliant twist is in the scheming of the Princess/Death, who kills Cegeste. In the Underworld she has him transmit his poetry to a car radio that only Orpheus can hear. He then transcribes the works and presents them as his own. The broadcasts are another clear nod to the legacy of the War, and of the French Resistance.

When his wife Eurydice (Marie Dea) is taken by Death, Heurtebise conspires with Orpheus to bring her back. But just like Death, Heurtebise has his own agenda. He is in love with Eurydice, and wants her to live again. There is a neat symmetry to the treachery both of the living and the dead. The foreshadowing of Heurtebise to Orpheus to be careful with mirrors is ominous, as he could quite unintentionally look in one when Eurydice is behind him, and doom them both.

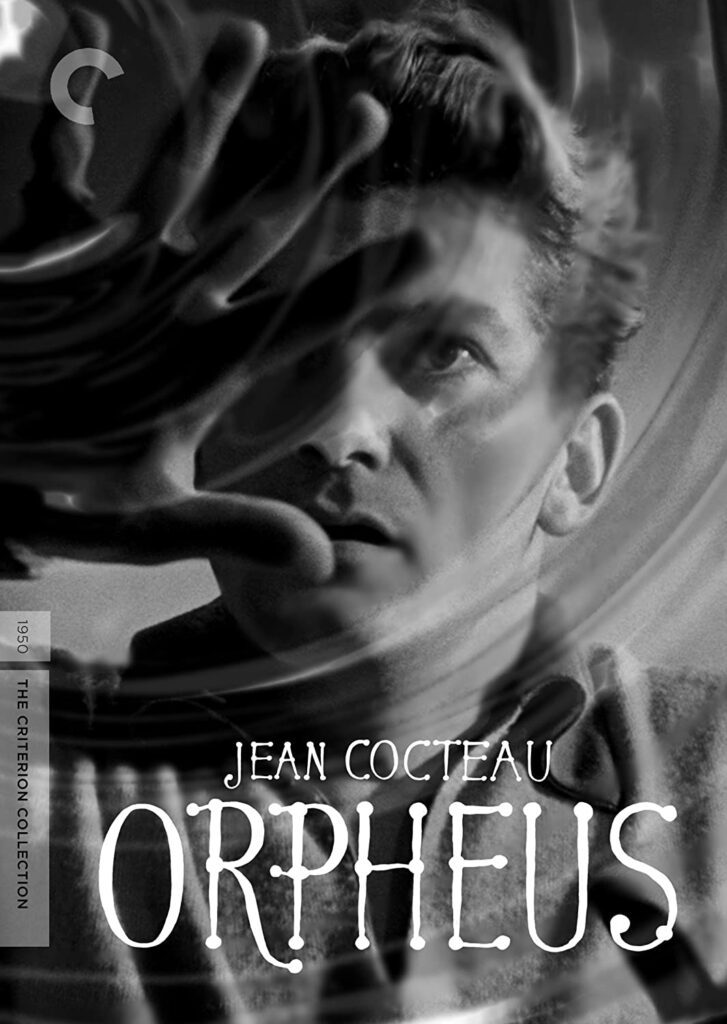

Cocteau constructed a masterpiece with Orpheus, it is a film that even today feels startlingly fresh. As is often the case with the Criterion Collection, the extras are almost as strong as the movie itself. In the case of Orpheus, an entire second DVD is devoted to bonus material.

The outstanding documentary Jean Cocteau: Autobiography of an Unknown (1984) is a 67-minute feature about the famed director. It is a fascinating portrait of Cocteau, but what I found even more compelling was the interview titled 40 Minutes with Jean Cocteau (1957). Another interview with him from the French TV program In Search of Jazz (1956) is only 18 minutes, but is still a very engaging conversation about his use of jazz in Orpheus.

These talks with Cocteau are all great, but he truly expressed himself via celluloid. A magnificent example of the care and dedication The Criterion Collection brings to their releases is the inclusion of La villa Santo-Sospir (1951). This is a 36-minute tour de force, shot in color and on 16 mm. It has never seen commercial release until now, and is his only venture into the world of color. Cocteau being Cocteau, the experimentalism continues – this time by using a strange process called contretype, which renders the natural colors an unnatural hue. La villa Santo-Sospir is presented as a documentary about his time spent at the villa, but of course it is much more. Cocteau uses the opportunity to rail at the film world, which had let him down with the disappointing box office of Orpheus. In many ways it is a much more candid look at the director than his interviews are, if unintentionally so.

Rounding out the supplementals are a video interview with Orpheus assistant director Claude Pinoteau, a 30-page booklet, the theatrical trailer, a gallery of stills by photographer Roger Corbeau, and some newsreel footage of the Saint-Cyr military academy – which played such a prominent role as the gateway to the Underworld.

Orpheus is every bit as powerful as its legendary status suggests. This definitive Criterion Collection edition not only does it justice, but provides a unique insight into Jean Cocteau as well. One would be hard pressed to come up with a better example of presenting a classic film than this.