Written by Mule

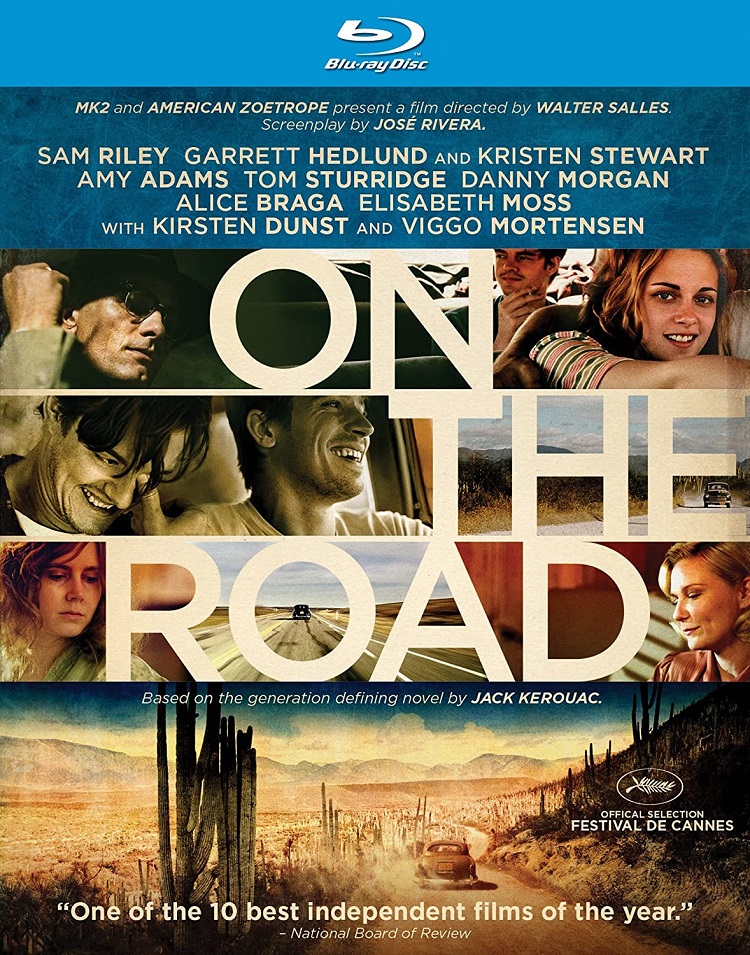

On the Road (2012) directed by Walter Salles is based on the Jack Kerouac novel of the same name first published in 1957, one of the main works of the Beat Generation. It’s not all that surprising that this fierce search for meaning and contexts still manages to fascinate a modern-day audience, especially since it lauds the cult of individuality and exploration.

The main protagonist Sal Paradise (Sam Riley) starts his more or less Odyssean journey of self-discovery shortly after the death of his father in a period of acute writer’s block. He is introduced to Dean Moriarty (Garrett Hedlund) by his friend Carlo Marx (Tom Sturridge). Dean is the very epitome of a free spirit. He has adopted an itinerant lifestyle rife with drugs and jazz and women, amongst which two in particular are of importance here, the young Marylou (Kirsten Stewart) and the more respectable Camille (Kirsten Dunst). It works in heavy contrast with the glimpses of the orderly life Sal leads, living with his aunt, when he meets the brash Dean. There’s an obvious fascination there, with someone who lives their life with such a hectic, exuberant intensity. Dean does come across as a poet warrior bad boy soul, rootless and restless, always willing to go-go-go. That’s the seduction.

The movie has definitely captured the spirit of the dream of the road trip, something that has seeped into the cultural subtext so permanently that it still lingers as a kind rite of passage, even when the roads and towns and adventures no longer exist in the same sense as they did back in the fifties.

Even if Sal is the central character, in a lot of ways this is Dean’s story, and the movie captures that fascination well. It also actually puts in some time on the road, which is much appreciated. Dean is behind the wheel a lot of the time, driving ridiculously fast and picking up hitchers and engaging in petty theft and drug use, and all manner of slightly left-of-center minor outlaw behavior, which is more seedy than malicious in its intent.

It doesn’t really translate, of course, the intense prose of Kerouac’s novel. It can’t. You should never really expect that, the mediums are so very different. The movie is grand and pretty, even when depicting squalor, but it’s never overly polished to the point where even poverty shines. There are enough lighting strikes to keep you entertained, but it never really leaves you breathless. The sex and drugs and rock’n’roll or rather, jazz, aspect feels surprisingly tame and anesthetized, but then we are a lot harder to shock these days. Jaded postmodernist nihilists are difficult to catch flatfooted by a little t-and-a, or by Dean selling himself to the dapper salesman played by Steve Buscemi.

The movie treatment is slightly more conventional than you could have hopes for. Serving the poignant, but hopelessly dated ideals of the book would probably have required more visual imagination. On the other hand the distance and detachment that seem to permeate the gaze of the beholder is much like the grief-stricken writer-blocked Sal Paradise, so I can understand the choices.

There are moments, though, that resonate. For instance the discussion between Carlo and Sal when Carlo talks about how he loves Dean and knows how futile that really is. Or when Sal and Dean turn up at Old Bull Lee’s (Viggo Mortensen) house to find Lee asleep with a needle in his arm and his son on his lap. Or in the very last moments where Dean shows up in New York looking worse for wear and Sal leaves him standing on the sidewalk.

Those of us who have read the book know that there is no real fixed narrative but that this is rather a story of characters, moods and places and visions and, above all, movement. All in all this is not a bad effort, but the one thing that I would have hoped for with a movie based on this particular novel is that it would leave me with a longing to go out on the road. Sadly, for me, that never happens here.