The essence of classic German expressionist cinema – particularly in the field of horror – is something many imitate, but which few can respectfully replicate in the long run. Indeed, director Werner Herzog created his own horror classic in 1979 with Nosferatu the Vampyre, his artistic take on F.W. Murnau’s now-iconic silent 1922 masterpiece, Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens. With the legendary visionary helming and the legendary creepiness and craziness (both onscreen and off) of his certifiably-insane lead actor, the infamous Klaus Kinski – who superbly mimicked the mannerisms of Murnau’s mysterious monster (offscreen as well as on), Max Schreck – Herzog was able to create something both artistic, atmospheric, and arousing.

And then the Italians invaded.

Nine years after Herzog’s film set its plague-infested rats across the sea of cinema, Italian producer Augusto Caminito (who also backed Abel Ferrara’s acclaimed King of New York) decided a sequel needed to be made. But certain things seemed to indicate that the project should not have been made; something that anyone with even so much as an inkling of common sense would have been able to deduce without questioning whether or not a sequel to a movie like Nosferatu the Vampyre needed to exist in the first place. But then, this is the same country that gave us their own “special” unofficial sequels to movies and/or franchises such as Dawn of the Dead, Jaws, Alien, and The Terminator.

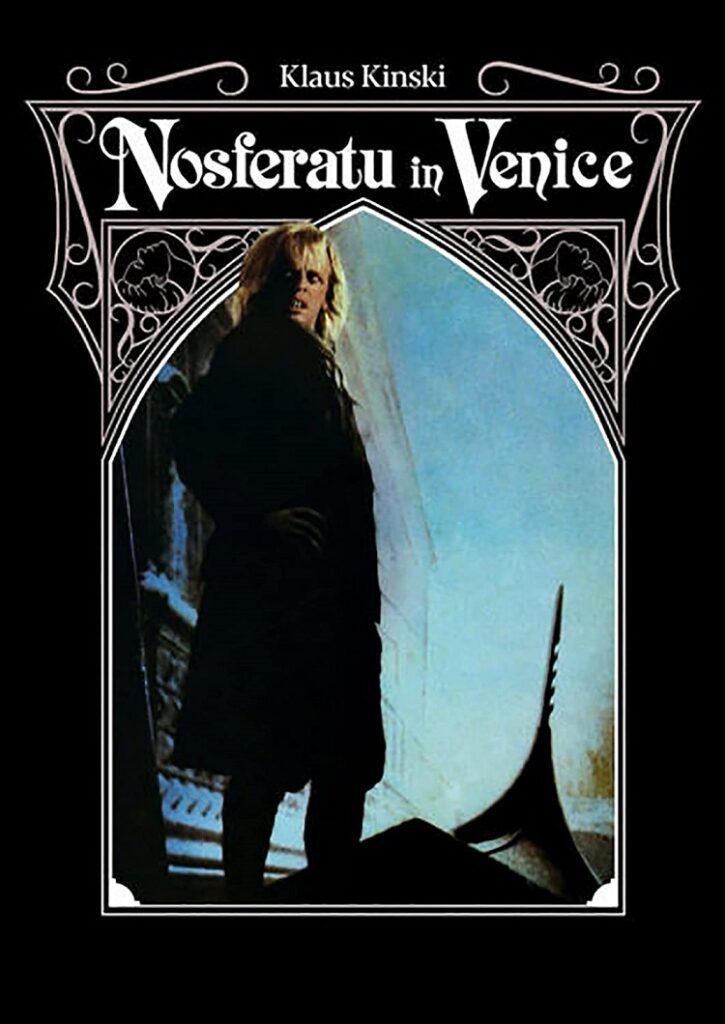

Of course, were it not for those aforementioned otherworldly forces that decided a Nosferatu sequel was a bad idea, Caminito’s Nosferatu in Venice may have actually wound up being an actual sequel. For starters, they managed to contract the leading star of the original (remake): Klaus Kinski himself. But wherever Kinski went, trouble followed. After already hiring and firing two different directors (both of whom walked away with full salaries, so well done there, gentlemen!) before principal photography even started, Caminito hired Mario Caiano (who not only brought us the greatest non-Mario Bava Italian gothic horror film ever, 1965’s Nightmare Castle, but also cranked out something called Nazi Love Camp 27 in the ’70s) to not only finish the film, but to start it too.

And then Klaus Kinski invaded.

Arriving on-set with the most outrageous head of long hair this side of a glam rock star, Kinski not only refused to shave his head and go through the four-hour-long makeup procedure to reinvent his eponymous character, squelching any and all hopes or attempts at making this a legitimate sequel; turning it into just another bizarre, trashy, in-name-only, Italian quasi-pseudo-sequel instead. Caiano experienced a violent argument with Kinski on the explosive actor’s first day to boot. The result? Caiano walked. With full salary. (Seriously, somebody get me a job with Augusto Caminito.) From thereon in, Caminito handled the already-troublesome shoot – with documented help from Luigi Cozzi and Maurizio Lucidi as well as alleged help from Klaus Kinski himself – despite having very little experience doing so. But then, something had to be filmed, and in the end, that’s exactly what they filmed: something.

Though Caminito managed to infuse his own sense of art, atmosphere, and arousal throughout, those elements appear either forced or unintentional here. Made in the late ’80s, when Italian cinema was withering as we knew it – too many unofficial sequels and ripoffs, no doubt (though I love those movies to death) – Nosferatu in Venice is a fine example of a once-prosperous industry having a stake driven through its heart. Scenes of people – living and undead – riding gondolas throughout the canals of the titular location, which there are many of here, fail to capture a feeling; likewise, gratuitous sex scenes featuring the (self-professed) hypersexual Kinski show the declining psychopath clearly taking many liberties with his female co-stars. It’s like finding Klaus Kinski’s sex tapes, and it’s not a pretty picture.

But then, the whole bleak picture, moving or otherwise, is not a pretty one. Like the movie it originally set out to be a direct sequel to, it’s a tale where happiness (much like art) is nowhere to be found; a sensation of hopelessness that ultimately prevailed for all involved, the final finished work even failing to make a profit in its own native Italy. (Of course, I suppose that could happen on any film if you gave three fired directors their full pay!) Onscreen, the dull depressing bits focus their malevolence upon co-stars Barbara De Rossi and Yorgo Voyagis, cast here as the story’s less-than-idealistic take on the romantic heroes who are only destined for doom once whatever passes for a story (three writers are credited, though there’s little indication any of them earned a full salary’s worth of work) attempts to kick into a gear (fortunately, De Rossi and Voyagis have prospered since, as no one saw Nosferatu in Venice upon its release).

And then there are the movie’s English-speaking guest stars; internationally known performers usually brought in for such projects to boost sales both domestically and abroad, and often to make a movie seem much better than it is. In the instance of Nosferatu in Venice, we have the billable talents of Christopher Plummer (an actor of rare distinction who actually managed to not only have a career after his made-in-Italy phase, but to avoid typecasting) as the Van Helsing-type scholar of the tale, and Donald Pleasence (who didn’t) as a cowardly priest. Another familiar face, though on a much lesser scale, that of American-born character actor Mickey Knox, appears as a much braver priest in a flashback (and who gets tossed out of a window and impaled for his overacting).

Apart from full frontal female nudity, I suppose the only other thing Nosferatu in Venice has going for it would be the previously mentioned Plummer and Pleasence. The latter – who played Dr. Seward in the 1979 American remake of the 1931 Universal Dracula – sticks to being in the back of the frame for the most part, joyously snatching an apple for his upcoming break in plain sight of the camera or snacking on caviar for realsies whilst delivering dialogue before finally coming alive at the end, ranting and raving à la his Halloween character, Dr. Loomis. Plummer, on the other hand, is probably the only actor to emerge with some sort of dignity; his ineffectual vampire slayer casually committing suicide after failing to defeat the unholy, undead villain after only one encounter (talk about sensitive!).

Naturally, Kinski may look like he’s involved in his character, too, in this, his penultimate feature. However, when you stop to consider that he’s clad like a New Romantic pop star (which goes well with the hair, I must admit) and that this film was made while the controversial actor was preparing to make what would be his very last movie, the self-obsessed and self-absorbed Paganini (which Caminito also produced), it’s most likely Kinski was Nosferatu as Paganini more than anything. (Side note of little interest: Luigi Cozzi, one of the uncredited co-directors of Nosferatu in Venice, made Paganini Horror in ’89 with guest star Donald Pleasence; that movie also failed to be a hit, and the director only made two documentaries after that).

For years, Nosferatu in Venice was a rather uncommon title in the world of home video. I recall it being available from mail-order companies back in the ’90s (those marvelous grey market distributors who culled their oft-fuzzy NTSC transfers from oft-fuzzy international video sources), but I never got around to ordering it. Perhaps if I did then, I might have enjoyed it more, as I was younger and more inclined to perceive myself as “artistic”. I would have also been more impressed at the transfer of the movie included on this One 7 Movies DVD release, which presents the film in its intended theatrical aspect ratio with the original Italian-language credits. (Don’t be fooled by One 7’s weird retitling, Prince of the Night – this is still Nosferatu in Venice any way you cut it.)

While the video transfer is definitely better than any ol’ VHS bootleg I could have picked up twenty years ago, I’m sad to say it ends there. Granted, the dual audio DVD does include the Italian-language dub (Italian movies are usually shot with its actors speaking English, phonetically or otherwise, and then dubbed into their native tongue), and there’s a short photo gallery included too, but the default English audio track for the feature film is as troubled as the film’s history and production itself.

(And then the avid fandubber invaded.)

Now, as a guy who spends too much time sitting in front of his computer engaged in the fine art of syncing audio from one source to the video of another – “fandubbing”, as some of us call it – I know that some tracks can be quite tricky. From the get-go, I could distinguish that One 7’s English audio had been taken from a videocassette source, evident by an unflattering warble sound amid the credits – something that could have been corrected simply by copying the music from the Italian audio track and pasting it in. And whereas I wouldn’t care so much about such a thing for a private fandubbing job, it’s a bit shoddy for a “professional” release such as this (and I use the term loosely).

Additionally, whoever the dolt responsible for syncing the English audio up to this video track was, he/she committed an unforgivable sin by filtering the hell out of it. A little filtering is OK if it reduces the humming and hissing so prominent in old videocassettes, but the noise reduction applied herein was strong that voices and sound effects now have an echoing and tinny quality that sounds akin to an MP3 file recorded in a very low, unappealing bitrate. Some people might not notice the aural imperfections as strongly as I did, having a pair of ears that are trained to discern such things, but it’s bad either way. I really have to wonder where the English audio track hailed from, and as to whether or not One 7 was behind the excessive noise filtering or not. (That said: One 7, I work cheap, do better work, and won’t expect a full salary if I quit on the first day.)

In short, Nosferatu in Venice (or Prince of the Night, if you really must call it that, though the title never appears onscreen) is a rarely-seen bad movie that has become even worse thanks to an unforgivably noticeable amount of noise reduction on the English audio track. Had the DVD sported some English-language subtitles for the Italian audio track, you could just switch those on and change tracks. Alas, such is not the case. (And I could have made fansubs for you too, One 7, just so you know.) Of course, Nosferatu in Venice isn’t a must-see item anyway, so I suppose none of this is entirely important.