“Do you ever have that feeling where you can’t tell if something is a memory or something you dreamed?” twentysomething Martha asks her clueless older sister Lucy midway through Martha Marcy May Marlene.

It’s just one of many good lines of dialogue in writer/director Sean Durkin’s new thriller, but it’s the creative crux of what makes his debut feature such an inventive treat. Arguably there was no hotter, more buzz-worthy ticket at the just-completed New York Film Festival, where Martha Marcy May Marlene played twice to enthusiastic, capacity crowds.

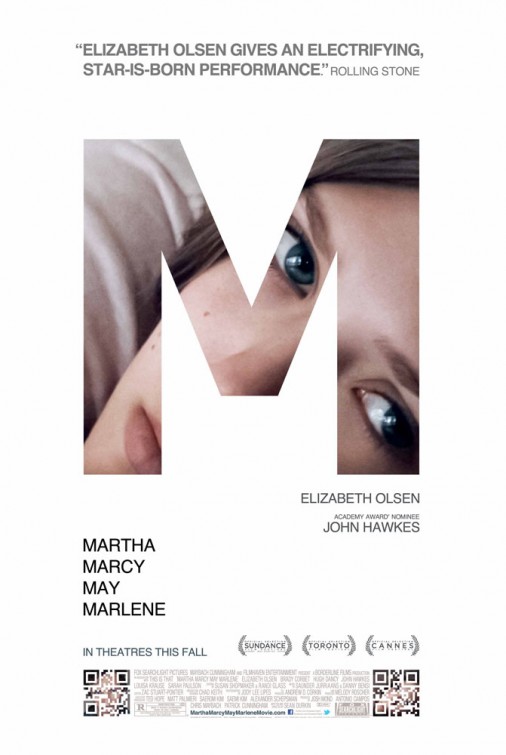

When first we meet beautiful, sad-eyed Martha (Elizabeth Olsen), she is desperately fleeing the upstate New York farm in which she lives communally with a small group of Abercrombie-esque waifs. She nervously calls Lucy (Sarah Paulson) from the last working pay phone in America and is picked up at the local bus depot, glancing over her shoulder at some constant, unknown menace.

Martha takes refuge at Lucy’s waterfront vacation home, but refuses to share details of the two years she spent out of touch, following the death of their mother. As she attempts to re-assimilate, the memories of her time at the farm begin flooding back and she becomes increasingly unclear about what is and isn’t real. The viewer shares her confusion, delightfully so.

As moments in the present trigger glimpses of the past, we learn that Martha was not living with her boyfriend in the Catskills, as she claims to her sister and brother-in-law. She was actually a member of a patriarchal cult controlled by a Manson-like sociopath (John Hawkes) and an active accomplice in chilling acts of rape, robbery and murder.

Durkin seamlessly interweaves Martha’s troubling backstory with her tentative pursuit of a new life, creating an overlapping dual narrative. This ingenious structure is part of what makes Martha Marcy May Marlene such a nail-biter. With no predictable storytelling rhythm to fall into, I was constantly on the edge of my seat, frustrated by a complete inability to guess what would happen next (but enjoying every minute).

It’s a creative masterstroke on Durkin’s part, one that allows the viewer (unlike Martha’s sister and brother-in-law) to fully understand and empathize with the character, despite her emotionless affect, terse replies, and generally unsympathetic behavior. Much of the credit for this goes to Olsen (younger sister of Mary-Kate and Ashley) who gives a nicely nuanced performance in her first leading role. (And if you like her in this, look for her in at least four more indie features, coming soon to an art house near you.)

In the pivotal role of Patrick, the guitar-playing cult leader, Oscar-nominee (for Winter’s Bone) John Hawkes is perfectly cast. We meet him in the film’s first flashback and, despite his backwoods creepiness, it’s easy to understand Martha’s attraction to him. There’s a hypnotic power in Hawkes’ weathered stare and, with Durkin’s deftly structured establishment of the character and his manipulative mastery, the premise becomes plausible.

In movies about cults or otherwise abusive situations, the viewer is often asked to believe that a protagonist (usually a woman, particularly if it’s on Lifetime) will choose entrapment because she’s damaged in some way, or because the aggressor has powers we can’t perceive. But there’s no suspending of disbelief in Martha Marcy May Marlene, particularly when it comes to Hawkes and the character of Patrick. I had a pretty good understanding of what these troubled young people saw in him and the seemingly idyllic lifestyle he was offering them – particularly at this moment in our political and socioeconomic history.

For example, Durkin opens the film with a pastoral montage of life on the farm: women washing clothes in old fashioned basins; men repairing a barn; young children being cared for in a safe, loving environment. Everybody has a role and everything is provided. In a time of rampant unemployment, poverty and economic uncertainty, this looks like a pretty good way to live, particularly for a college-age kid who hasn’t yet established an adult identity.

Movies and television, particularly thrillers, tend to mirror the fears and phobias of the day. Science fiction of the 1950s was often a thinly veiled allegory about the dangers of the atomic bomb, or the Red Menace or both (if it was written by Rod Serling). In the late ’60s and early ’70s, as women fought for equality in the workplace and the bedroom, Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby and The Stepford Wives were parables of sexism and powerlessness.

With today’s insurmountable economic inequality and the attacks on women’s sexuality and reproductive freedom from increasingly aggressive Conservative lawmakers, what disaffected young woman wouldn’t consider living in a free love commune with a guy who writes songs about how pretty she is? I know I would, but I’m a sucker for a guitar-playing psycho.

As you may remember, both Rosemary’s Baby and The Stepford Wives end unhappily for their young female protagonists. The conclusion of Martha Marcy May Marlene is uncertain, just like everything else in 2011. Today, as always, art imitates life.