Battles Without Honor and Humanity has been called the Japanese Godfather, and while it has some similarities (depicting daily life of gangsters, where formality and ritual places a veneer of civility on brutal criminality) it has a completely different tone. There’s a sepia-tinged nostalgia to The Godfather, with Michael Corleone’s rise in power and his subsequent decline in humanity looked on with a sense of tragedy.

The Battles series, directed by Kinji Fukasaku and largely written by Kasahara Kazuo, was an intentional demystification of the yakuza. Gone are the stoic and honor-bound modern samurai of earlier yakuza films. In Battles, the top boss cries to get his way with his reluctant men, oaths of loyalty are immediately followed by betrayal, and every assassination attempt is a frenzy of confusion and chaos, with cowards running away from each other and would-be killers firing blindly somewhere in the direction of their victims. Told with a semi-documentary style and, at least in the first two installments, based directly on the memoirs of real Hiroshima gangsters, Battles Without Honor and Humanity was an enormous hit, spawning four sequels in two years.

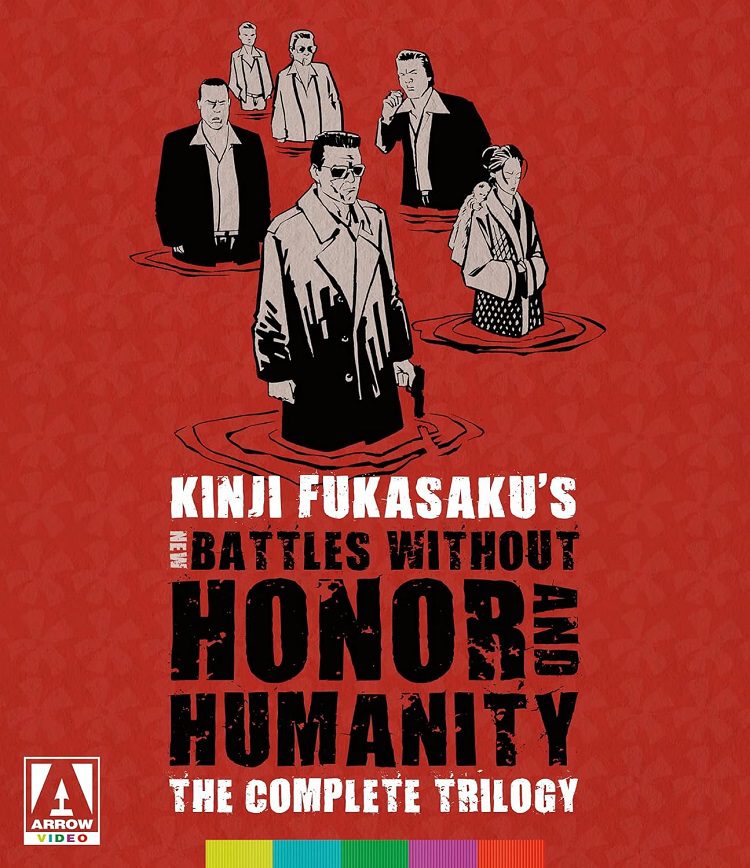

While the real stories of gangster life may have run out, audience enthusiasm for them hadn’t, so Fukasaku directed a second series of films, cleverly titled New Battles Without Honor and Humanity. Gone are the real-life stories (each movie begins with a title card stating “This film is a work of fiction”), gone is the original writer and gone is the continuity – each of the New Battles movies has a different main character and a different setting. Strangely enough, they still all star serious, grim-eyed Bunta Sugawara in the lead.

In the original series he was Shozo Hirono, small-time gangster whose honor held him back from advancement and led him to be taken advantage of by less scrupulous gangsters. In New Battles Without Honor and Humanity, the first film in this very loose trilogy sequel, he plays Miyoshi Makio, a very similar character in very similar circumstances to Shozo in the original.

He’s a member of the Yamamori crime family who botches an assassination attempt, and after spending time in jail comes out and finds very little waiting for him in return for his sacrifice. He’s torn between Yamamori, the big boss (the one actor playing the same character as in the original series), and the head underboss Aoki, both of whom expect Maki to kill the other, and don’t expect to pay him for it. New Battles has a similar rhythm to the films earlier in the series, being mainly a collection of conversations between men in formal halls, in dining rooms, and in brothels, telling each other about their honorable intentions and then scheming behind each other’s backs.

These are punctuated every so often with scenes of frenzied, often ridiculous violence as yakuza, usually youngsters without the sense to know better, try and kill older men for their boss’s honor with varying degrees of success, and almost universal incompetence. As such, New Battles sometimes feels like a near parody highlight reel of things that were done in the earlier series, pushed to their extreme. When one of Makio’s underlings wants to impress another boss’s men his seriousness, he gouges out one man’s eyes. Just to make a point. One cowardly underboss who wants to remain in Yamamori’s good graces makes an enormous show of trailing Aoki, going so far as to communicate to the boss from a building window several blocks away, using semaphore. It’s amusing and interesting… but also nothing really new for a fan of the original films.

For the next two movies, thankfully, Fukasaku and his writers (particularly Koji Takada, Fukasaku’s frequent collaborator) moves away from simply rehashing what had already been said and done in the original trilogy to vary the tone and content. The Boss’s Head opens with Bunta Sugawara playing Shoji Kuroda who helps Kusunoki, the son in law of a yakuza boss, go on an assassination. Unfortunately, Kusunoki’s a junkie who has to get high before the attempt, and is as competent with a gun as any of the yakuza in these movies. Kuroda was just going to take the fall for Kusunoki – instead, he commits the murder himself. It’s one of the interesting details of yakuza life that these movies reveal that, when the brutal crimes are committed, it is assumed that someone will have to go to jail for them. The yakuza have arrangements with the police, and as long as someone in the organization will pay, the crimes go largely uninvestigated.

After spending seven years in prison Kuroda expects a reward, but it turns out that backing a junkie to be an effective gang leader wasn’t a smart play. Kusunoki’s a wreck, but Kuroda still wants his money. If Sugawara’s Makio in the previous movie was essentially the same as his character in the first series, only a bit dumber, drunker, and less scrupulously honorable, Kuroda is a complete inversion. He’s nasty and violent and ready to inflict pain on whoever he needs to get what’s his. The Boss’s Head is much more of a gritty action film than the previous Battles films, but it contains much of the flavor that permeates the series, including a penchant for the bizarrely funny: when Kuroda finally pushes Kusunoki to get the money, the two kidnap his boss and his mistress and force them to dig their own graves in the rain. How this is supposed to get him to fork over the money is an open question… but it works.

The final film in the series, The Boss’s Last Days, moves even further into the action genre, while keeping the flavor of the series. The question of honor is again at the forefront: this time, Bunta Sugawara plays Shuichi Nozaki, a low level yakuza who spends his days running a legitimate shipping operation, and has completely separated himself from the life, other than visiting the boss who took him in when he and his sister were orphaned. He doesn’t really want anything to do with the yakuza, but when his boss is killed (by a transvestite masseuse, naturally) he sets out on a course of single-minded revenge that turns everyone, friend and foe, against him.

Everyone except for his sister, played by Chieko Matsubura. A slim, narrow-faced beauty, she played the regular love interest in the Outlaw Gangster VIP series (playing six different characters in the six movies – including two different love interests in one) and is the culmination of the Battles series growing interest in the female characters who support their yakuza. In the initial series, besides boss Yamamori’s unctuous and grasping wife, there are few stand-out female characters. In particular, Bunta’s Shojo never gets any sort of love interest in the whole series.

The New Battles has at least one interesting woman per film: in the first film, Reiko Ike, one of 70s Japan’s biggest pinku stars (a style of low-budget soft core erotic films) plays a Korean prostitute who thinks that Makio is actually falling for her, when he is just using her as a human shield. There are two important female characters in The Boss’s Head: the great Meiko Kaji from Lady Snowblood and Female Prisoner Scorpion plays a long-suffering wife of the junkie Kusunoki, while Yuriko Hishimi is a scheming black widow who might take up with Kuroda, if he happens to be moving up in the underworld.

This new interest in female characters tracks on of the reasons Fukasaku is such an interesting director to follow – however quickly he made his films and however much he stayed in the same lane (in the ’70s alone he made more than a dozen yakuza movies) his curiosity and creative energies were always in motion. Even when retreading the same ground, and the first New Battles film is something of a retread, there are still new angles being explored and some scenes we haven’t seen before. The original Battles Without Honor and Humanity is required viewing for anyone with an interest in 70s Japanese cinema, Fukasaku or yakuza movies in general. While the same can’t be said for this “trilogy”, there’s still plenty here to engage the interested or even mildly obsessive viewer.

New Battles Without Honor and Humanity: The Completely Trilogy is an Arrow video release. The films all look their age – they were shot relatively cheaply in the ’70s, and are appropriately grainy in appearance. The set of extras on these discs are unfortunately not as comprehensive as one might have wished from an Arrow video release. The fact is, a great number of the contributors to these films are no longer with us: Fukasaku is almost 15 years gone, and Bunta Sugawara died three years ago. Each disk contains, besides a trailer, one newly produced extra: on New Battles, there’s a short appreciation of the series by a Fukasaku biographer, and the other two each have a discussion by the film’s writer and frequent Fukasaku contributor Koji Takada. The box set also include a booklet with useful essays on the films.