Written By Ram Venkat Srikar

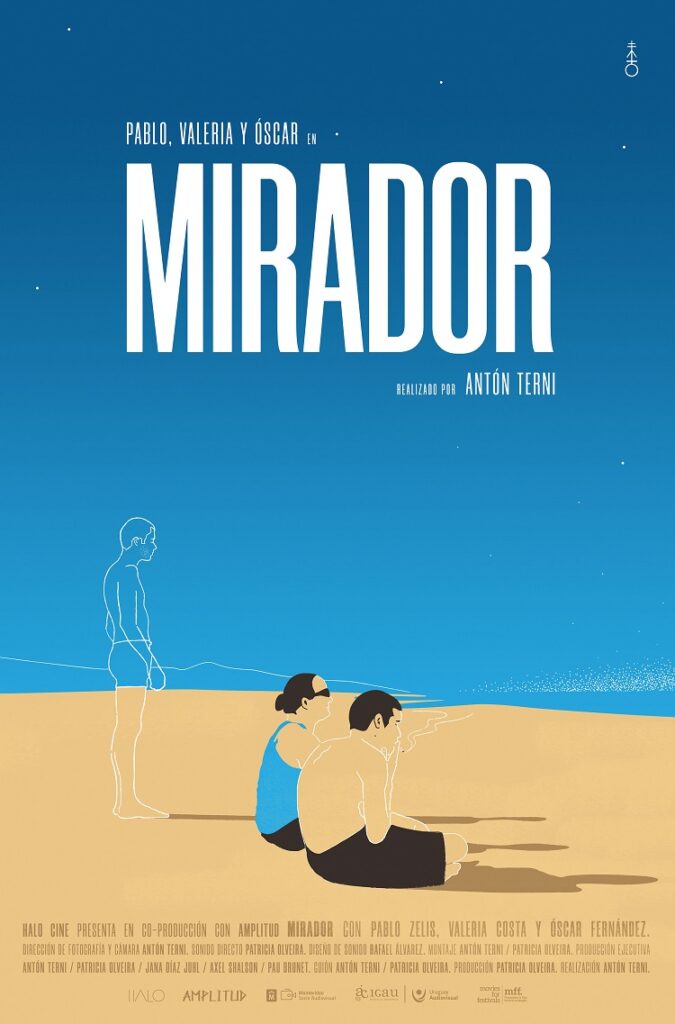

In Spanish, Mirador means “lookout.” The word has multiple connotations. Alertness, observation, prediction, or a person assigned to keep an eye on his surroundings. The last of the aforementioned undertones befit the documentary’s subject matter, that encircles three friends and the solidarity among them. The irony, though, is all of them are visually-impaired, meaning they can’t keep an eye on each other literally, but their support is persistently up for grabs, figuratively.

The locale is a secluded and sylvan rural part of Uruguay, where the film’s prime subject, Pablo Zelis, leads a simple and tranquil life. He records and listens to conversations from the past on cassette tapes, and brews liquor. This reiterates multiple times through the 70-minute runtime to assert his daily routine. It’s plausible that the ataraxy in Pablo’s lifestyle is misapprehended as wearisome or bleak because it adheres to a simple pattern as far as what we are shown. That’s the notion the filmmaker Antón Terni tries to create, only to break it 13 minutes into the film, when Pablo, along with his friends Valeria and Oscar, ventures into the woods on a camping trip. The trip metamorphoses into the soul of the film, as it bestows Pablo and the viewers a break from the prevailing monotony, and exhibits the vitality of seeking the little highs in an otherwise plain life.

Antón Terni, who is also credited as the editor and cinematographer, is inclined towards showing over telling, but the chore of comprehending is left to the viewers, as good art does. Terni captures lucid yet profound moments of the trio, especially through the hiking trip with a pit stop at the beach. After Pablo and Valeria jump into the water, it is now Oscar’s turn to do the same. Upon Pablo’s pep up, Oscar comes close to the water and as his feet feel the waves, we witness a child-like exhilaration, nervousness, and delight on his face. Such organic moments cannot be created, and capturing such minuscule facets in all their purity is no easy job either. The risk of branding it pretentious always exists, but Terni’s camera gets hold of at least half a dozen of such moments of unadulterated joy, which ensure we resonate with these personal, teeny-tiny moments.

Although there’s a substantial amount of dialogue, the film’s reliance on visuals and the underlying fundamentalism is such that the story would retain its comprehensive essence even if the film refrains from providing vocal cues. Converging back to the film’s gist, it speaks volumes regarding how companionship mutually bolsters those involved in the bonding to surge past their personal blemishes, thereby adding color to life. Not a single instance in the film italicizes the fact that these three are blind. It treats them solely as humans, like you and me, and marks no difference. Mirador urges us to look out for those surrounding without verbally telling us to. Mirador exhibits the fruitfulness of amity, without actually underscoring it.

The trio’s conversations, hang-outs, and celebrations are akin to just another group of friends, and the lack of contrariety impels us to live and love a bit more.