Written by Kristen Lopez

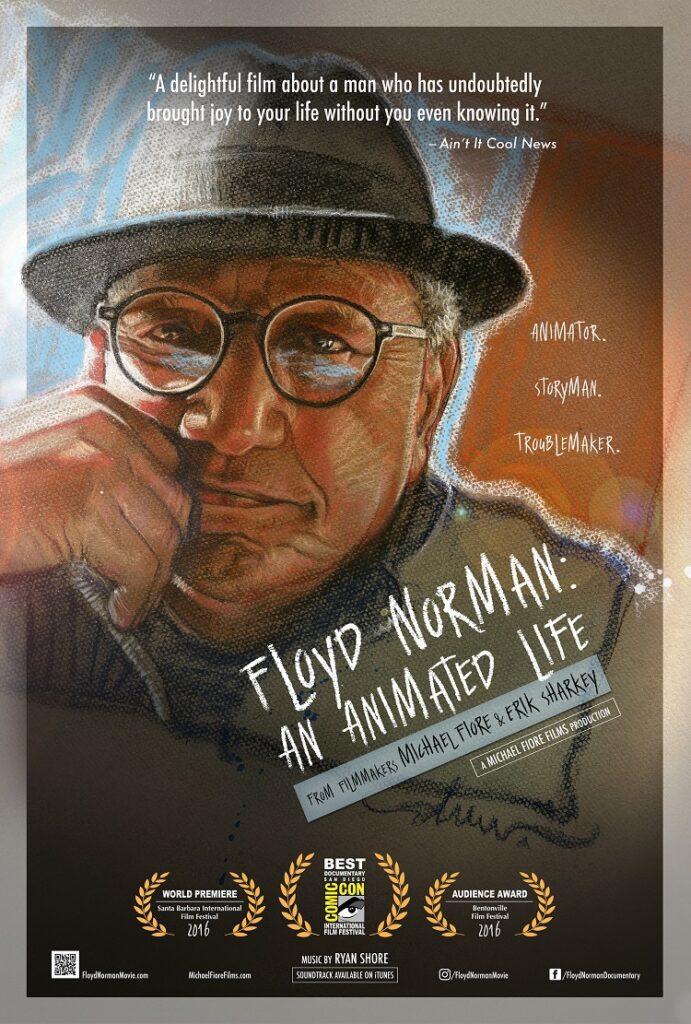

Floyd Norman is an animator with a big heart, and that’s evident from hearing Michael Fiore and Eric Sharkey – the directors of Floyd Norman: An Animated Life – discuss him. They sat down with Cinema Sentries to talk about Norman, the editing process, and what happens when you’re following the nicest man in the world.

What was your background with the Walt Disney Company? Were you guys just fans of the studio or was there something more?

Michael Fiore: We have no connection with the company. We are both Disney lovers and grew up on the great movies. As far as making the movie, there wasn’t any direct connection to the company throughout the process. They were aware of the movie, certain departments were aware. Our connection to the company itself was Floyd.

Eric Sharkey: I met Floyd at the Los Angeles Comic-Con. I was there promoting a documentary about poster artist Drew Struzan, who did a lot of work for LucasFilm. I was introduced to Floyd and that’s when he told me all these great stories about working at Disney. It’s not often you meet somebody and they say, “Oh, when I worked with Walt Disney on The Jungle Book.” That stops you in your tracks that he actually worked with Walt Disney. I thought it would make a great documentary because he’s had such an amazing life and career; he’s so personable and charming. Luckily Michael reached out to me; he was looking to make another film. He loved the idea too, so we started the process.

MF: After Eric met Floyd at Comic-Con. Eric and I met in the early winter of 2014, so it was probably six or seven months after he met Floyd. The tie that binds Eric and I is our mutual friend and composer, Ryan Shore. Ryan had just worked on Eric’s last movie, Drew: Behind the Poster. I was kind of curious; I had just come off another movie that comes out this winter called Keep Watching from Sony Screen Gems. I was looking for the next movie and when I heard more about Eric I was curious to see what he was up to next. I called him and he pitched a bunch of things, and one of them was Floyd’s story. I was in shock. I thought, “Wow, this is a total no-brainer. How has no one done this?” I took a week or two. I looked online and did my due diligence to see if his story had been exploited, and it hadn’t. I circled back to Eric and sat down, got coffee and lunch. It was very clear we were feeling each other out as collaborators, but we got along great. It was like, “Let’s just do it.” Two to four weeks from the time we first sat down we were in California and at Floyd’s house, Disney animation taking the tour with him. The rest is history. It came together very quickly.

Watching you guys go into the animation studio and the Walt Disney Family Museum was just amazing. You got the ultimate insider’s peek.

ES: There’s a lot to love in this movie. You’re right, that animation building on the Burbank lot where so many classic films were made and where Walt Disney’s office was, going around with Floyd and hear his stories were amazing. And to have people throughout Disney history who had done so many films be so supportive has been amazing. There’s definitely a lot to enjoy for Disney fans about the history of the studio, the films and the company through Floyd’s story.

MF: The movie is so layered. It’s a love letter to animation; it’s a love letter to Floyd. We always say, “We made a love story” [and] it really is. It’s about a man’s love for Disney, his art, his animation, his family, his wife. What’s great about it is you can come away from it not only understanding a man, but for a younger animation enthusiast they can come away with a really broad sense of, not only the history of animation through Floyd’s eyes, but a general understanding of how it’s done. It’s not a how-to make animation movie, but I’ve had people come up to me after we’ve had our screenings and they’re like, “Oh my God, I didn’t know that was part of the process.” I think that’s so cool when a movie can educate on so many levels. When we see it with audiences Eric and I are amazed. They’ll laugh at spots we’d never thought they were going to laugh at. The experience of seeing it in a theater is different than seeing it at home because we watch people – the laughter amongst people – they engage each other.

ES: Floyd has also done such great work outside of Disney, working for Hanna-Barbera, working on all those classic shows we grew up on. He and his partner Leo did the intro for Soul Train. Floyd has had a rich life throughout the history of animation.

Floyd’s such an amazing presence. People naturally gravitate towards him. What is he like as a subject?

MF: Somebody said in a review we read yesterday that they almost didn’t believe us as filmmakers; that’d we’d editoralized his story to the point we’ve made him nicer than is humanely possible to be a nice man. We both found it really funny because it’s like, no, having followed him for a good portion of time, that’s who he is. Floyd is an onion with lots of layers. He has an angrier, darker side, and he vents it through his art and his gags. What’s so funny is he has a huge heart and it shines through. We talked to him and there’s no bad day; there is no bad moment. He greets everyone equally the same.

ES: He’s always happy to share stories of his life, his experiences, his knowledge of animation. He’s so generous with doing drawings. He’ll sit there for hours, doing drawings for anybody who wants them, and he’ll go till the last person. He’s happy to share his talent and experiences.

How much input did he have on his portrayal? Was there anything he didn’t want on-camera?

MF: He was an open book. There was a point when we’d realized that on certain subject matter he wasn’t gonna budge. We learned that you need to hit him at an angle. You have to find out information from someone else, and then when putting him back on-camera you’d hit him with “So, your wife said that X, Y, Z happened. Can you break those events down?” It sounds like he’s being forced into a corner, but now there’s a concept that’s been validated. For instance, racism in Disney. He didn’t really deal with much of it at all, but there was one episode very early on. For the first few months that we met up with him, he was all “No, Disney was great.” I want to be very clear, we’re not talking Walt Disney the person; we’re talking about the corporation. His wife Adrienne said to us, “No, there was one time in particular” and it’s documented in the movie. We hit him with that on another interview weeks later and said, “Adrienne said you had this issue with somebody or some people?” And he went, “Oh, yeah, that did happen” and he went into it. You ended up being a detective; it’s like a procedural murder mystery. How do you get to his soul without being too intrusive?

ES: He was great about giving so much time to us. Anytime we wanted to film him, anywhere, he’d always show up. He was extremely generous with his time. Michael’s right, if you heard his story from someone else, and you came back to him with it, you’d discover new things about him that previously he wouldn’t have gone into.

MF: The challenge making the movie was we sat there with over 100 hours of footage. As you can with any movie, you can skin the cat a thousand different ways. We were continually shooting and editing simultaneously, and we would learn something new which opened up another rabbit hole. Eric and I would have a discussion of “He mentioned three new people. This is a great story. Should we get these three people on-camera?” He’s an unending well of stories and creativity. For a filmmaker it’s awesome, but it makes for a twisty rabbit hole when you’re making the movie.

Well with that, was there anything that ended up on the cutting room floor that you’d hoped to include?

ES: There was a lot on the cutting room floor because of how much footage we had. In terms of the narrative, the film flows so well that it’s the film it should be. Depending on what your interests are – if you’re interested in Hanna-Barbera you could go on and on. You want to keep it to a great, tight narrative, so I don’t think there’s much we could have put back in that would have made the film better. There’s a lot of great outtakes on the floor, that’s for sure.

MF: Eric hit it on the head. It wasn’t a matter of making anything better; it would have made it different. We had a cut where there was more time spent on his divorce and his familial dealings, and that’s a different movie. You’re covering 80 years of someone’s life with an emphasis on 50-60 in animation. When you start paring it down to a year about his divorce, if you spend more than three minutes on it in a movie that’s about animation, there’s an imbalance. That was the tricky balancing act when Eric and I got together in the editing room, determining “That’s really good or that’s really dramatic.” Even if it was great drama it takes away, tonally, from what the movie should be. If there was one thing we didn’t get that would have been awesome to have was a former boss of Floyd’s at Disney who was a pivotal part in his forced retirement. I had a phone conversation with him, off the record, where he explained why it all went down. He was going to appear on-camera, but he pulled out. I hounded him for a year as we were editing and his office said “No, he’s traveling.” We did everything in our power to say “We will come to him, wherever he is in the world” for a ten-minute interview. We never got it. We don’t have any commentary from Disney about what happened there, and that’s not from a lack of trying; they just didn’t want to go on-camera. That would have escalated the movie to a more dramatic place.

Disney does tend to be very controlling about their employees. Have you heard at all from anyone in Disney, the higher-ups, about the documentary? How do you hope they respond?

MF: We haven’t gotten any word yet. I’m sure in the next week we will. There’s only about ten minutes [in the film] where we’re hard on Disney, but it’s in an objective way. We’re not sitting there like Michael Moore saying, “See! You guys are the bad guys!” We’re saying, “Tell us what you know.” By the accumulation of their ideas it’s very clear that Floyd was forced to retire [based on his age] because it was his birthday, and that’s a fact. I don’t think anyone at Disney can be upset because it is a fact. The reality is, without giving away the ending, they do redeem themselves within the context of the movie. I don’t think there’s any reason for them to be upset, and we hope they see it as a love letter to not just Disney, but the whole art of animation.

ES: Floyd has made it clear that, for the most part, he loves Disney. He’s very good at sometimes taking loving jabs at the company for things he disagrees with. Overall, he’s always said Walt Disney was the best boss he’s ever had in his life, and he’s had this long history going all the way to Pixar. If he criticizes, it’s with love, but overall he’s had an amazing career he’s very proud of.

You see Floyd sketching and drawing throughout the entire movie. Did either of you end up with a Floyd Norman drawing at the end?

ES: We were very lucky that we filmed him doing a lot of drawings. We were left with a stack of drawings he did on-camera for us.

MF: I was just Googling something with regards to our movie, people are selling his drawings on EBay. Somebody wanted $100 for it. I thought, “That’s awesome.” He’s become that guy who people are selling his art which is pretty cool that’s happening for him.

[Read Kristen’s review of Floyd Norman: An Animated Life]