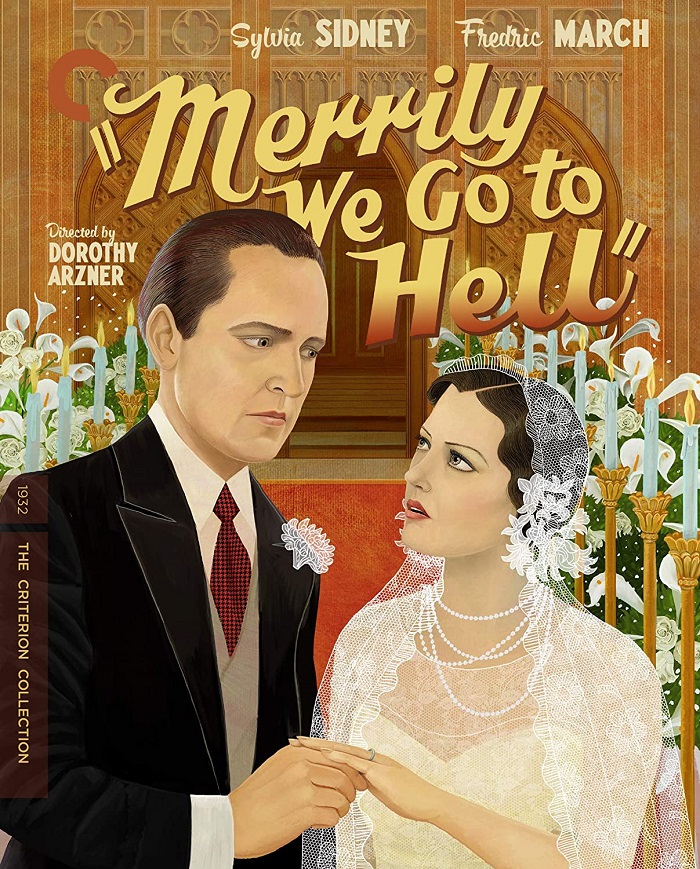

Legendary filmmaker Dorothy Arzner was a trailblazer. She was the only female working and directing during 1930s and ’40s Hollywood. She brought her own style and technique to films, especially those with mature and adult subject matter. She also heralded a feminist sensibility to her work, which even now seems contemporary and relevant. With her 1932 pre-Code masterpiece Merrily We Got to Hell, she boldly tackles modern marriage.

Based on a short story Cleo Lucas, the film opens with Jerry (a beautifully pathetic Fredric March), a struggling playwright and newspaperman, already drunk at a high-society party. He encounters a young woman named Joan Prentice (Sylvia Sidney, whose soulful persona has never been better), who takes a liking to him. They talk, flirt, and kiss. She also invites him lunch the next day, if he can remember what time to arrive. During the next scene, Jerry hasn’t shown up for Joan’s party, and she feels as if the whole thing was just tiny fling. However, he does arrive, which definitely lifts her spirits. He takes for a drive and dinner, where he tells her that the only other woman in his life ruined it. But it’s water under the bridge. Soon after, they immediately get married (despite her father’s skepticism) and have a whirlwind marriage. Things are good at first, and Jerry’s recent play gets a green light. However, his alcoholism gets the better of him. Even worse, the woman from his past, beautiful blonde and starlet Claire (Adrianne Allen) comes back into his life, for which his eye wanders to. This definitely pushes Joan over the edge, where she ends up experiencing and experimenting with open marriage. Knowing that he has really messed things up, Jerry realizes that he really loves her. He gives up Claire, and goes to seek Joan’s forgiveness. When he finds that Joan has had a baby, he rushes to her in a hospital. He learns that the baby has died, but he tells her what she’s always wanted to hear: “I Love You”. In this case, Jerry and Joan have reconciled.

There is a modernity and freshness with this film that many others at that time (with the exception of 1936’s Dodsworth) failed to truly get the essence of. It’s themes of addiction, polygamy, and female empowerment were out there in open before such things were even talked about. Not only that, it successfully showcased the falsity of high-society, where the rich and privileged seem to have all, but in realization, they have just as much baggage and unhappiness as everyone else. These themes are remain incredibly fresh today.

Both Sidney and March give astonishing performances as Joan and Jerry. Sidney with her deep expressive eyes and demeanor and March’s magnetism and versatility definitely mesh well together. They have chemistry that feels real and organic. You totally believe them as this urbane couple who go through the ringer, yet come out together on the other side. Their acting is genuine, and not something that’s just there for awards recognition. It’s the type of fully fleshed-out acting that seems ancient now.

Despite the light supplements, such as a new video essay by film historian Cari Beauchamp, and a 1983 documentary on Arzner, I still think this release should be a must-have for film buffs and collectors, especially those who want more diversity and women’s cinema in their collection. And don’t forget the great new essay by film scholar Judith Mayne.

I think Merrily We Go to Hell is a revelation, and a prime example of Arzner’s legacy; one that truly deserves a new renaissance. I’m glad that Criterion is committed to making that happen, not just with her groundbreaking films, but those of other female filmmakers as well. Women can make films and tells stories too.