Georges Simenon created Commissaire Maigret in 1931. The character starred in 76 of the author’s novels and 28 short stories. They have been translated into dozens of languages and adapted into numerous films and television series. Like Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot before him, Maigret has become one of the world’s most famous fictional detectives. I’ve never read a single word of the stories but have previously watched and reviewed two other adaptations (one with Bruno Cremer as the great detective, the other with Michael Gambon) and now with Maigret Sets a Trap and Maigret and the St.Fiacre Case that total will come to three.

Truth be told, while I enjoy both Holmes and Poirot quite a bit when it comes to detective fiction, I’m more of a hard-boiled man. I want my murders “taken out of the Venetian vase” as Raymond Chandler once put it, and dropped “into the alley”. If these adaptations hold true to Simenon’s vision, then the Maigret stories fall somewhere between the works of Agatha Christie and Dashiell Hammett. He is not the super-sleuth using his inhuman powers of deduction nor his little grey cells to solve a case, but rather shoe leather and years of experience. Yet sometimes, as we’ll see in The St. Fiacre Case, the recently murdered are countess’ living in country estates, and they conclude in a parlor with a gathering of suspects.

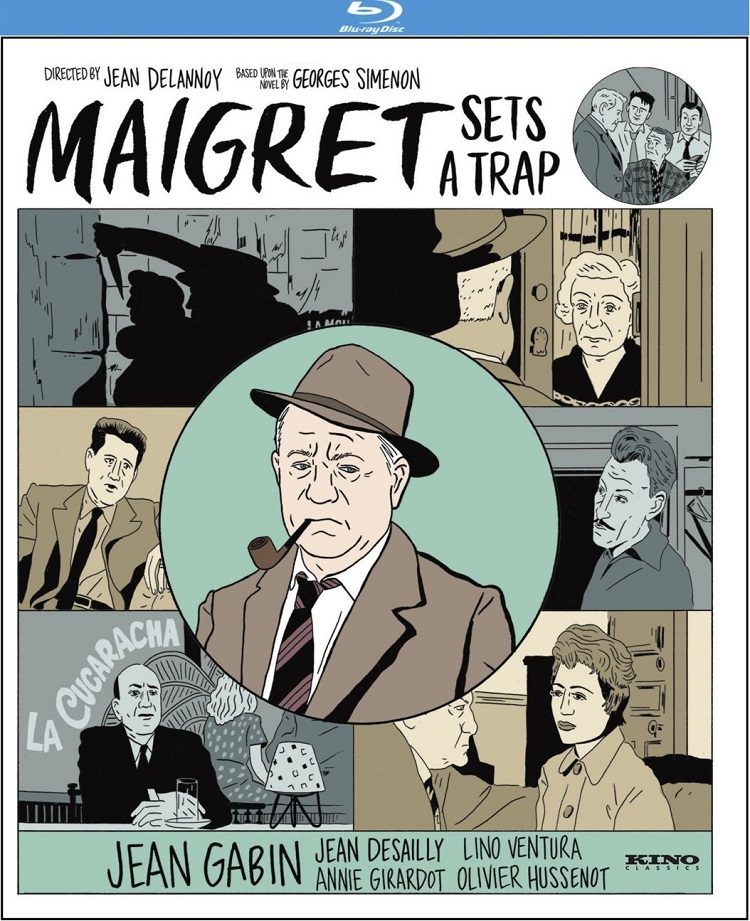

Made in 1958 and ’59, it is likely these two films were American’s first glimpse into the world of Maigret. It is the great French actor Jean Gabin who dons the pipe here (he made one other film as the Inspector, Maigret Sees Red, but it has not been released on Blu-ray in the States and the DVD version seems to be out of print).

Gabin plays Maigret with a world weariness. He’s seen enough of crime and would rather be relaxing in his home with his wife and a good pint, but crime never ceases, and Magret keeps getting called back to the streets. He does seem to enjoy throwing his (rather significant) weight around and delights in showing up to a place or placing a call and making action happen simply by stating who he is – the great detective who never loses.

These two films demonstrate just how well Maigret can exist in both the upper-crust society of Poirot and the dirty streets of Phillip Marlowe. In Maigret Sets a Trap (originally titled Inspector Maigret, but now renamed presumably to fit the original story’s title), someone is killing young women on the streets of Paris, and Maigret must jump into the seedy world of strippers and prostitutes to solve the crime. He sets multiple traps to catch the killer. First by placing many coppers on the streets then by making all the women in the precinct wander about alone hoping to catch the killer’s eye. Later, he reenacts the murders as a performance piece hoping the killer will show up to watch. When one detective spies a woman paying close attention, he follows her – not to her home but to a seedy hotel where she meets a man who is decidely not her husband.

Maigret interviews her, then her husband and his mother, and then interviews them again desperate to get a confession. Gabin is a great actor but it gets a bit tedious watching him talk to one person and then another without a whole lot of other action taking place. The ultimate revelation is a nice twist but not all that surprising.

In Maigret and the St. Fiacre Case, the detective travels back to his childhood village after his old friend, The Duchess of Saint Fiacre, has received a note stating she shall be dead by Ash Wednesday, just a few days away. When she winds up a corpse just as the note predicted, Maigret must rekindle old friendships and brush the dust off the old mansion. It seems since her husband died many years ago the great house has fallen into disrepair. Her son hits her up every few weeks for more money to maintain a lifestyle the estate can no longer afford, causing her to slowly sell everything off. A series of incompetant secretaries have made bad investments for her and it seems everyone has a hand out. The local priest may have her ear but probably not her best interest at heart. Maigret steadily speaks to everyone, slowly unraveling a complicated case in which there is plenty of guilt to spread around.

Jean Delanoy directs both films and does a fine job. He’s not what his soon to be contemporaries in the French New Wave would call an auteur but he creates some pleasing pictures with his camera and moves the action right along. They both have the problem of putting Maigret into a room with the suspects at the end of the film for an overlong interrogation and explanation, but for the majority of the length they are quite enjoyable little murder mysteries.

The St. Fiacre Case gets my vote as the best of the bunch, which is surprising because as noted I tend to like my detectives to get down and dirty and mingling with the upper class. But The St. Fiacre Case is filled with lots of interesting characters and a beautiful, moody old mansion, and Maigret Sets a Trap gets bogged down in several long interrogations, which finds Jean Gabin doing nothing much but yelling.

But both are very enjoyable and do serve as a nice introduction to the classic character for those who are not familiar with him. Both films have also been cleaned up really nicely. The whites are clean and the blacks bold. It’s a very crisp-looking transfer with a nicely cleaned up audio as well. The only extras are trailers for each of the films.

Inspector Maigret has stayed in the public’s imagination for nearly a century. His everyman persona with a dogged way of solving the case will surely keep him there for many more. These two films are well made, thoroughly entertaining stories and will make nice additions to the crime lover’s collection.