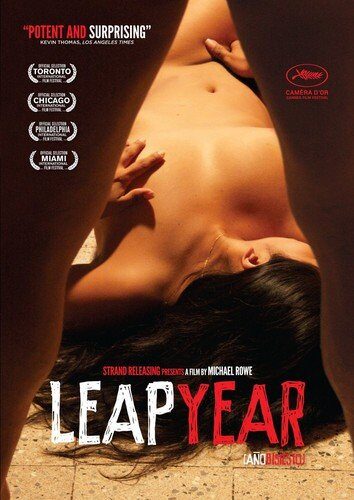

There’s not much respite for Laura (Monica del Carmen), the plain freelance journalist who’s onscreen nearly every second in Michael Rowe’s measured, thoroughly disheartening Leap Year. Save for the film’s opening scene where Laura eyes an attractive man oblivious to her longing in the grocery store, the entire film takes place inside her drab Mexico City apartment.

There’s some significant cognitive dissonance going on here, as Laura’s descriptions of her life to people on the phone (steak dinners, relocation to Switzerland) are fantastic substitutes for reality (beans straight from the can, masturbating while watching her happily domestic neighbors). All the while, Laura is counting down the days, making big black Xs on her calendar that lead to an ominous February 29th slot, colored entirely in red.

It’s plain to see that Laura is dissatisfied and lonely, but the black depths of her despair aren’t immediately apparent. In the few instances where she has some non-telephone contact, it’s usually with a random one-night-stand, and her resulting disappointment when he sneaks out rather than spending the night seems standard, clichéd even.

Thus, her relationship with Arturo (Gustavo Sánchez Parra), a random lay who actually sticks around and begins seeing her regularly, seems to be wish fulfillment for our lonely protagonist. And then his sexual identity begins to come into clearer focus. Some slapping around leads to cigarette burning and then knife play and urination.

The situation seems clear — she’s so lonely, she’ll be used in any way that blunts the isolation, no matter how humiliating. But Rowe subtly turns expectations on their heads, revealing more and more about Laura until we realize she’s the one who’s using Arturo, and his masochistic fetishes may just be a means to escape her pain.

The film belongs to del Carmen, who is in every scene and shows remarkable naturalism whether partaking in another cheap, pre-packaged dinner or working from home in one of her fleeting flashes of employment. The film never allows us to understand the inner workings of her pain fully, but a scene where she describes a violent fantasy to Arturo is both intensely disturbing — far more than the physical acts onscreen — and deeply sad. She unassumingly lays her soul bare.

Rowe shoots digitally with mostly natural light and uninspiring surroundings, which makes for a rather cheap look. But while the visuals are unremarkable, Rowe smartly blocks his scenes and let’s them play out unflinchingly, with only the banal diegetic sounds of life in a crappy apartment heard. The film itself might be even more downbeat than it sounds, but it’s an impressive writing and directorial debut from Rowe.

Strand Releasing gives the film a solid showing on DVD, presented in its original 2.35:1 format. The digital source ensures colors are a little muddy and it’s not the sharpest image around, but it’s a clean digital transfer. The DVD features no extras aside from trailers for several other Strand releases.