Some movies offer formal challenges as part of their appeal. They might have sequences of the narrative where the viewer doesn’t know exactly what’s going on or in what sequences they’re shown. They might have elliptical stories that really require an interpretation rather than just unfolding the narrative directly for the viewer, like a David Lynch film. Or they might have a different way of showing images on screen that is unconventional. Entire film movements are built around recognizing the “rules” by which films are made, and then subverting or even ignoring them.

And then there’s Kiju Yoshida’s Japanese New Wave movies, which throw convention into a blender. Not content to experiment with just the narrative or the look or the sequencing of his films, Yoshida’s style pushes against all kinds of formal limits, while somehow at the same time maintaining a discernible story and thematic sense. However idiosyncratic his filmmaking is, it maintains enough internal integrity to be something more than just “experimental film”. Whether that integrity is enough to get an interested viewer through some very challenging watching is a real question.

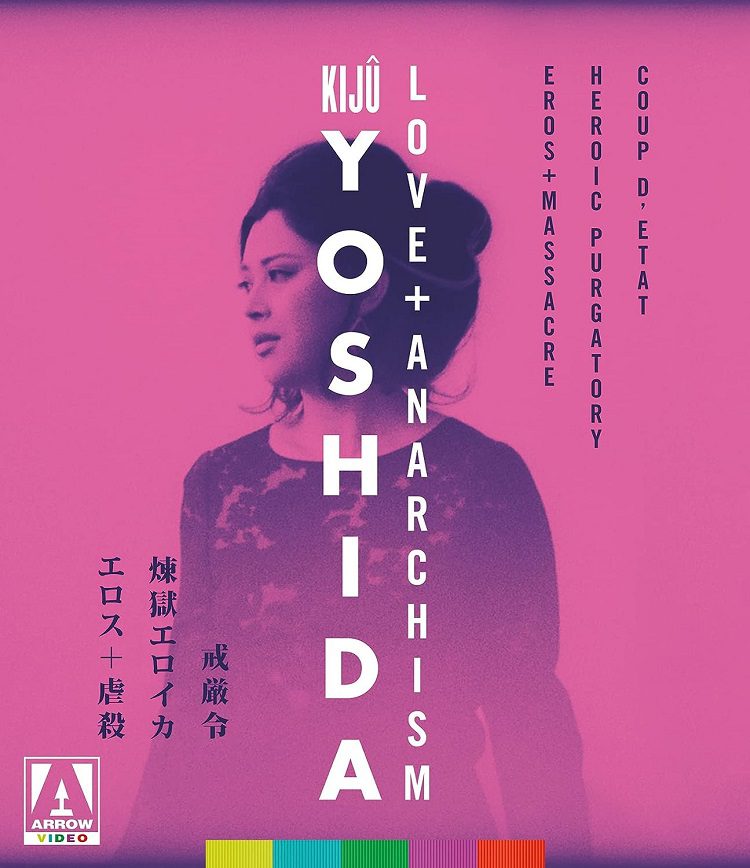

In Love + Anarchism, Arrow Academy has released in one package a loose trilogy of films Yoshida directed at the end of the ’60s and into the early ’70s: Eros + Massacre (available here in the original two and a half hour theatrical edition and in a mostly restored director’s cut which adds nearly an hour of material), Heroic Purgatory, and Coup D’état. All three are about radical politics in Japan both throughout its history and in the modern (late ’60s) day, and all three use radical filmmaking techniques to reflect not only their subjects, but the filmmaker’s attitudes towards them.

Eros + Massacre, the most famous of Yoshida’s movies, is a monolithic slab of cinema in the director’s cut: three hours and 35 minutes of sometimes obscure, sometimes humorous, always baffling but often engaging filmmaking. Its story has two major thrusts: two students in the ’60s, the girl a sometimes prostitute and the boy a firebug, meet and decide to go on a trip with each other. The prostitute is studying the life of Sakae Osugi, an important early 20th century anarchist who was murdered, along with his wife and six year old nephew, when military men feared an anarchist coup after the Great Kanto earthquake of 1923 devastated local governance. Sakae Osugi was an early advocate for woman’s equality, and also for free love. He openly carried on a relationship with three women at once, which didn’t turn out so well for him: when one of the mistresses didn’t end up being his preferred, she stabbed and tried to murder him.

This stabbing plays out in one of the largest sequences of the film, replaying three different times with different actions and effects, different witnesses and perpetrators. Playing with what actually happened in historically significant events is one of the major concerns of the film, as is the effect of the past on the present. To show this, Yoshida intermingles scenes and setting from both eras without much concern: when a country girl travels to Tokyo in the 1910s, it’s a modern train and station she rides on in her historical outfit. About midway through the film, the two students bump into one of Sakae’s mistresses and interview her like it was a newscast. Past and present are intertwined and moved through, events are related with little concern for their chronological sequence, and there are no on-screen credits or tell us when is when, who is what, and where anybody actually is. Plots are brought up and dropped as their thematic significance wanes – early in the film a cop arrests the prostitute, but later seems simply more interested in interrogating her about her profession than pressing charges, then he disappears entirely from the film.

Beyond the challenging narrative, Yoshida’s visual style is also different and rather extreme, particular in his compositions. The subjects of each shot are hardly ever in the center or fully framed. Heads tend to be right at the top or bottom of the frame, the rest of the image filled up with their surroundings. A large number of shots are deliberately over-exposed, so that the image takes on a ghostly, dream-like quality, and much of the background is washed out white. It’s a very particular style which can at first look like complete mis-framing, but as one gets used to it it’s actually quite striking, and the images Yoshida and his cinematographer displays are almost uniformly beautiful. Eros + Massacre is almost entirely dialogue scene after dialogue scene, but as best I can recall absolutely no simple traditional shot-reverse shot, one talkers face then the next one’s face scenes in this film. There are no scenes that seem to be built, in the typical fashion, of having a master shot that plays out the scene with inserts and cuts breaking up what is essentially an already constructed whole.

This formal experimentation is taking even further in Heroic Purgatory, an extremely elliptical story about a man remembering, from his current normal life, his radical student days in a Japanese communist cell. Or perhaps it is about his wife’s anxieties about them not having children. Or about the girl who is their daughter but one they never actually had. Or about an attempt to kidnap an ambassador that didn’t work out. All of these various plot threads are contained in this movie, but none of them are directly addressed. There are scenes that might be from the past, but that contain characters from the present (or at least what seems to be the present at the beginning of the film) who are in different roles. Some scenes involve two similar actions intercut with each other so only deeply attentive viewing can tell when one scene or the other is taking place. Sometimes characters disappear off camera in one direction and appear coming back on in the opposite. There are individual scenes that are touching, or humorous (as when the botched attempt to kidnap the ambassador from the ’70s is criticized by the rebels in the ’60s, who show up on the scene. Or maybe it all happened in the ’80s, who can tell?) As a whole, Heroic Purgatory lives up to its name: watching this movie is very much like being between two places at once and never getting anywhere. Maybe that’s an allegory for the Japanese Communist party. It is, at least, not three and a half hours long.

Coup D’état, the final film in this set and, for 13 years the final film Yoshida made (apparently by his own choice, since his productions were made by his own company and at least partially self-financed) is by far the most straight-forward of the films, both in its storytelling and formally. While Yoshida’s compositional habits are maintained, this story of a right-wing philosopher, Ikki Kita, who was the well-spring of an attempted coup on the government in 1936, is told relatively in order. This might be because the Japanese audience would be more familiar with the circumstances – Ikki Kita is still read in Japan, and the events of the coup, called Niniroku jiken, meaning the ‘2-26 Incident’, lead to Ikki’s execution even though he apparently played no direct part in the coup.

In the film, Ikki Kita spends most of his time, when not saying sutras in front of a Buddhist shrine, trying to guide a (fictional) young soldier away from taking part in the direct action against the government that his works have inspired. The story takes place over several years, from the early ’30s to 1936, but no passage of time is indicated, and many of the major events of the film take place off-screen, related in dialogue. Though not nearly as elliptical as the other films, Coup D’état is determined to make the audience work to get much out of it.

Ikki Kita is played by Rintaro Mikuni, one of mid-century Japan’s most prolific and acclaimed actors. His performance carries a sort of wounded gravitas, a solid anchor in the murky revolutionary plotting that makes up much of the film’s narrative. It’s a testimony to Yoshida’s strength as a director of actors that, in the midst of his intentionally confounding directorial choices, the performances in his films are uniformly strong. The anchor in both Eros + Massacre and Heroic Purgatory is Mariko Okada, who plays in those films respectively the doomed mistress and the revolutionary’s wife. She was also (and still is) Yoshida’s wife. Eros mixes acting styles in its differing narrative eras, with the actors of the past characters much more formal and stylized than the more free-flowing naturalistic acting of the contemporary characters.

All of the stylistic choices Yoshida makes are a very deliberate attempt to shift cinematic form to demonstrate his ideas, even if in so doing it makes those ideas rather obscure. As a lover of the formal aspects of cinema and Japanese New Wave in particular (French New Wave movies for whatever reason always leave me cold) I found Yoshida’s work difficult and fascinating. Were I to break out one of these films on a movie night with my buddies, I would never be allowed to pick a movie again, and would probably lose all of my friends.

Arrow Academy’s release of Love + Anarchism has the normal plethora of Arrow extras, primarily in the form of commentaries and introductions by Japanese New Wave scholar David Desser. These introductions discuss briefly the history and style of the films, and are handy at getting a grasp on what is some very difficult cinema. The commentaries are a little unusual – rather than a straight-through commentary on the entire film, each movie has Desser’s comments on a select number of scenes. Interesting as far as it goes (though it might have been a bit too casually edited – at one point Desser fumbles some words and asks if he can start over the recording. Apparently, the engineer said no) Desser provides a useful inroad into the films, though with material this dense I might have preferred commentary on the whole films, if just to hear if someone else was as confused as I was. Also included is a short documentary about Eros + Massacre including an interview with Yoshida himself, and introductions to Heroic Purgatory and Coup D’état by Yoshida, as well as a 76-page booklet of essays and photographs that provide more context for Yoshida and the films. All three films are black and white. Eros + Massacre and Heroic Purgatory both look particularly luminous on the Blu-ray, while the transfer for Coup D’état seemed softer and less distinct.