In 1954, four of the most famous people in the world were Joe DiMaggio, Marilyn Monroe, Joe McCarthy, and Albert Einstein. Playwright Terry Johnson wondered what it would be like if all four of them got together somehow one night. It is a curious premise, as these personalities could hardly be more different, yet all were equally celebrated. Underlying this unlikely event was the painful reality of the Cold War. Only nine years had passed since the bombing of Hiroshima – at 8:15 on August 6, 1945, and there was an almost palpable fear of nuclear annihilation.

Cut to 1985, some 31 years later, and the Cold War has heated up considerably. Ronald Reagan’s “Star Wars” initiative was designed to launch the arms race into space, and nobody knew just how strongly the Soviets would react.

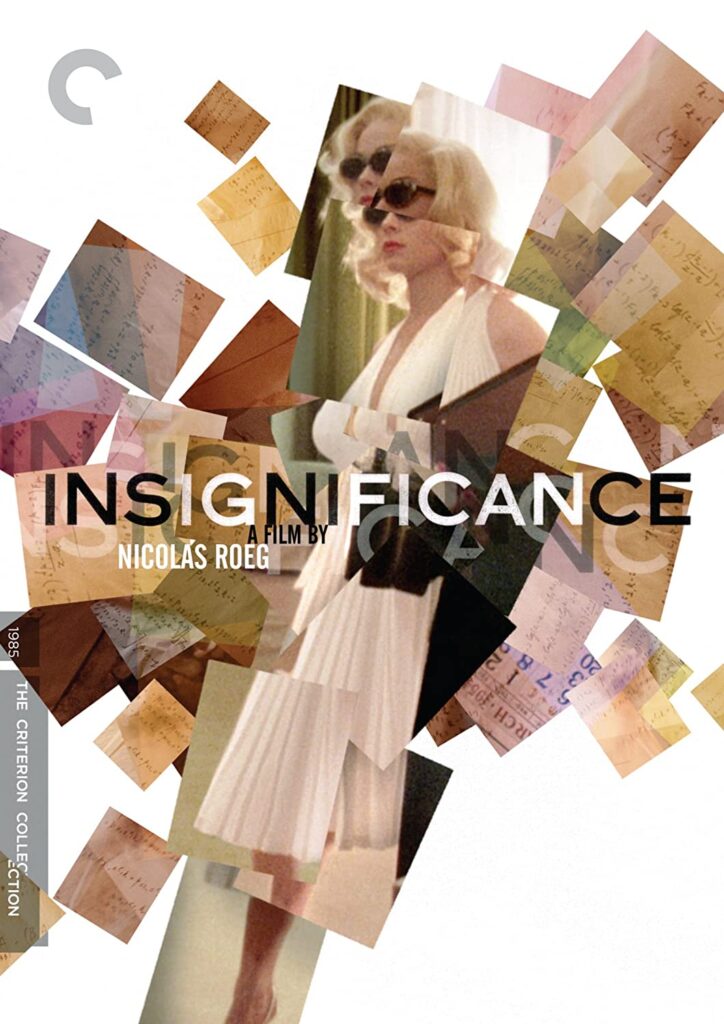

It was in this historical context that Nicolas Roeg’s Insignificance (1985) was made. Terry Johnson adapted his play into a script that went much deeper than the original had, in fact writer Chuck Stevens calls it a “Mobius strip masterpiece.” The idea of the single-sided continuous time loop – that the world of 1985 was much the same as the world of 1954 is a major theme, but there is even more to the film than that.

The four main individuals are never formally introduced by name. Rather, the Marilyn Monroe character is referred to as the Actress (Theresa Russell), Joe DiMaggio is the Ballplayer (Gary Busey), Joe McCarthy is the Senator (Tony Curtis,) and Albert Einstein is the Professor (Michael Emil). The vague anonymity allows Roeg and Johnson room for a bit of dramatic license.

For example, there is no evidence that Marilyn Monroe ever offered herself sexually to Albert Einstein, as happens in Insignificance. There was an autographed photo of him found in her effects after her death though. This discovery was actually the initial impetus for Johnson’s play, which began with him speculating on what these two very different souls might have have discussed.

The movie opens up during a nighttime shoot in Manhattan. It is the iconic scene from The Seven Year Itch (1955), where Monroe’s white dress flies up when she stands over a vent. For those paying close attention, Nicolas Roeg makes an almost imperceptible cameo as a member of the crew here. Thus the juxtaposition of time is instantly established.

The film is being shot right in front of the hotel the Professor is staying in, and it is in his room where most of the action takes place. While the Actress’ famous scene is playing out, the Professor is visited by the Senator. Amidst a room full of handwritten notes, as well a chalkboard filled with inscrutable mathematical equations, the Senator is cajoling him to testify at the HUAC hearing. The Professor is having none of it though, and shows him to the door.

We next find the Actress making an unannounced visit to the Professor’s room. Their conversation is very disjointed, neither one is able to make much sense of what the other is saying. Then the Actress breaks through by explaining the theory of relativity to him, using toy trains as props. He is suitably impressed, but still declines to sleep with her.

Meanwhile, the Ballplayer is sitting in a bar down the street, where a calendar of his soon to be ex-wife is on the wall next to him. Although the date says March 1954, this is obviously not a calendar that would be on the wall of a bar in the early fifties. The picture is from the famous first issue of Playboy, December 1953 – featuring Monroe as the centerfold. The picture has been cut-up, Cubist-style and rearranged – and now appears as if through a kaleidoscope.

The kaleidoscopic nature of thoughts, actions, emotions, and time seem to be the larger overall picture Roeg is after. Memories become distorted, there is the sensation of déjà vu, and there are inexplicable actions people take, which they themselves cannot even later explain. All of these combine to question the very nature of reality, or more precisely – our perception of reality.

The random series of events continue with the Ballplayer disgustedly ripping up the calendar, then going to the Professor’s room to confront his wife. In another room, the Senator is attempting to entertain a hooker, who laughs at his impotence. There is a mysterious observer to all of the various psycho-dramas taking place this fateful night, in the guise of the hotel’s elevator operator. He is a tall Cherokee Indian (Will Sampson) whose enigmatic presence hints at the supernatural. It is as if he alone holds the secret as to how all of the confusion in the air will resolve itself.

Through all of these human dramas, the time 8:15 continuously appears, most notably on the Professor’s watch, which is frozen there. It also appears often during the numerous flashbacks each character experiences. These refer to pivotal moments in each of their lives, from the recent and distant past. These episodes further develop the theme of time’s carefully sewn quilt quietly unraveling before us. The Professor also has a reoccurring vision of cities in flame. His guilt over having opened the scientific door that led to the development of the atomic bomb is obvious. Late in the movie he tearfully murmurs to himself, “We burned children.”

Roeg and Johnson’s screenplay expanded the play’s scope immeasurably. The nuclear terror that underpins the film was added, and the apocalyptic closing scenes tie all of the loose ends into a perfect package. As Roeg states about the title in a reprinted 1985 interview, “What it means is not that it’s all insignificant, but that nothing has more significance than anything else.”

The remastered Criterion Collection edition of Insignificance includes a video piece titled “That’s Insignificance,” by Duncan Ward, Tom Ward, and Nico Roeg Jr. This is a behind-the-scenes documentary, shot during the filming of Insignificance, and featuring interviews with the cast. It runs 14 minutes.

There are also two interviews shot specifically for Criterion in December 2010. The first is with director Nicolas Roeg and producer Jeremy Thomas, the second with editor Tony Lawson. Each of the segments are approximately 14 minutes in length.

Insignificance is very much a product of its time, as Roeg points out. The fear that the Cold War had heated up immeasurably under Ronald Reagan was the driving force. Those superpower standoff days have been replaced 26 years later with fears of smaller, and in some ways even more frightening threats. But the point really is the same – that there is significance in everything. By blending the past with the (then) present, Roeg managed a rare feat: a film about time which itself is timeless.