I think about James Baldwin quite a lot.

I think about his writings and his teachings.

I think about the fact that he could have just stayed in France and ignored what was happening to Black Americans in the United States. Baldwin could have actually turned a blind eye and not returned to the country that he actually loved so much.

But James Baldwin was not that kind of man.

One of Baldwin’s most famous quotes is “I love America more than any other country in this world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” This is from Baldwin’s work, Notes of a Native Son.

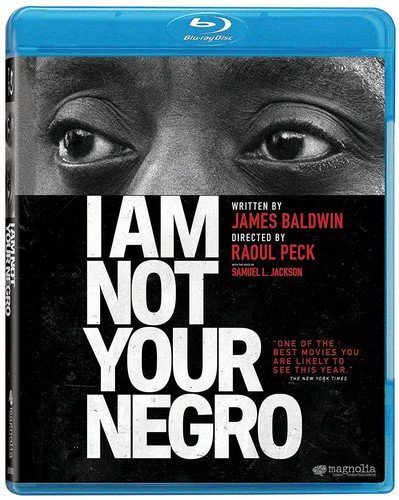

It is exactly this kind of loving and important criticism that director Raoul Peck brings to the screen in the film I Am Not Your Negro.

I Am Not Your Negro is a film 10 years in the making and it is probably one of the most important films of our time.

It has taken me a long time to write this about this film because in considering James Baldwin and I Am Not Your Negro, I cannot just be a reviewer.

I have to remember and recognize my academic training as an American Studies scholar who studies race and ethnicity, and American ideals and institutions.

I have to remember and recognize my responsibilities as an American citizen.

I have to remember and recognize my position of power and my privilege since I am not a person of color living in the United States.

As a reviewer, I could easily just write about the film and point out all the important visual connections that Raoul Peck makes by juxtaposing Baldwin’s words against cinematic scenes of white hegemony.

But a surface level review full of “sophisticated” observations doesn’t serve anyone.

As a scholar, I could do a heady close reading of the film and point out what other people should find important since this film confronts race and institutionalized racism.

But as a scholar, if I point out things that are important, I have to believe those things are important for me to see too.

As an American citizen who is not a person of color, I could just assume that the issues that Peck addresses through James Baldwin in this film do not affect me.

But these things do affect me because they affect my family, my co-workers, and my friends.

And those are just some of the reasons that this review has taken me a long time to write.

James Baldwin set out to write a book entitled Remember This House, about the lives and deaths of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and how the lives of these three men, as Baldwin put it, “banged up against” one another.

These three leaders were all Black men, fighting on different battlefields, for the rights of men and women. Yet within a span of five years, Evers, King, and X were all assassinated.

Medgar Evers was assassinated on June 12, 1963 at the age of 37.

Malcolm X was assassinated on February 21, 1965 at the age of 39.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968 at the age of 39.

These three men were taken down in the prime of their lives and in the prime of their fights.

These are three lives that still bang up against Americans today since their fights still continue.

Remember This House was never finished. What Baldwin left behind was the initial 30 pages of the book and the book proposal that he wrote to his literary agent. These are the words and ideas that director Raoul Peck used to build the foundation of I Am Not Your Negro on.

Posthumously, James Baldwin narrates this film through the vocal talents of Samuel L. Jackson who has embodied James Baldwin for the film. Throughout I Am Not Your Negro, Peck puts together collages of images from classic Hollywood films and current events like the conflicts in Ferguson and juxtaposes these images with the words of James Baldwin. These juxtapositions are broken up with interview footage of Baldwin from some of his television appearances.

What James Baldwin was writing then, he could have just as easily been writing in present day. He could see things were not really changing for people of color in America. That although some strides had been made in terms of Civil Rights, Black Americans were far from being seen as equals in the eyes of the citizens at large.

This film resonates with Americans today because it is clear that as a nation we have not learned the lessons that Baldwin was trying to teach.

As Americans, we are quick to grieve when tragedy strikes in other countries, far away from ours. We will turn on the filters on social media and post about how are hearts and prayers are with those faraway people.

It is easy to grieve with those who are faraway because we can claim to want to do something, but in turn we really don’t have to do anything. But when tragedy strikes at home, what are we really doing for our neighbors and those in our own community and country? Because if we begin to grieve for the people that just as easily could be our friends, family, or neighbors, we have to begin to question what could we have done or what should we have done to ensure that such tragedy does not happen again.

I Am Not Your Negro is a film that needs to be seen and a film needs to be taught. This film also needs to be viewed more than once. Although it is only 93 minutes, Peck gives the audience a lot to consider and to question.

Through Baldwin’s words and teachings, Peck is showing America and the world that colorblind ideology does not work. Peck is reflecting back on the many Americans that are still using peculiar language to describe a peculiar institution whose tenants set the tone for a racial hierarchy.

James Baldwin saw what was happening during the Civil Rights movement and he knew that the issues that people of color faced in the United States would not go away by just wishing it so. People had to and still have to change. Language had to and still has change. Policy and laws had to and still have to change. But in order for those changes to happen, America and Americans have to admit and accept that this country has been built on two genocides. The first being the genocide of the Native Americans and the second being the genocide against Black Americans of African and Caribbean decent.