Three-dimensional television sets with Ultra High-Definition 4K resolution. A kajllion-and-one useless apps for our increasingly useless smartphones. A vast array of challenging social networks that only go to make people vastly socially-challenged. With some new revolutionary thing we allegedly cannot live without coming ’round the bend every other week, it’s easy to not fully realize we live in a world that is literally littered with nothing more than a shitload of gimmicks. More than half a century ago, studios and distributors alike were also worried the public might soon stoop so low as to pick up a book and learn something, that they began their plight against the vile loathsome “freenessness” of free TV.

The result? Gimmicks. Gimmicks as far as the eye could see. Further than that, in fact; stretching beyond the ordinary realm of mankind’s traditional senses by promising to heighten them, all the while performing oft-blatant attempts to heighten the net value of a select few. 3-D. 4-D. Sensurround. D-BOX. Anamorphic Duo-Vision. Hypnotisms. Folks in monster masks being given free reign to terrorize patrons in the auditorium (and who had, presumably, not been convicted of any sexual offenses as of late). There were even several presentations with supposedly totally valid offers to bury you for free should you die of fright during frighteningly dull horror movies (with caskets optional on the West Coast because… wait, what?).

Of course, you can’t mention a movie gimmick without invoking the anaglyphic apparition of William Castle, who introduced the world to such seat-fillers as Percepto, Illusion-O, and Emergo (and who inadvertently inspired Alfred Hitchcock to make Psycho in the process). Inevitably, said gimmicks wound up alienating the very people they were aimed at, raking in everything from complaints about headaches to lawsuits instead of piles o’cash. Ultimately, these weird little footnotes help to make what is perhaps one of the most intriguing chapters in the annals of motion picture history. Likewise, there is one gimmick movie in particular that best sums up the whole sordid affair: a movie whose marketing ploy targeted our very nasal passages, proudly advertised “First they moved (1895)! Then they talked (1927)! Now they smell!”

And most of the (relatively few) people who were able to see Scent of Mystery the first time it made its way to theaters in 1960 as a roadshow engagement wholeheartedly agreed that the movie did indeed live up to its hype. If they ever add a word like “post-bizarre” to a dictionary, Scent of Mystery should undoubtedly be featured as the corresponding photograph, as it was one of the few movies ever to advertise the various odors one encounters in a crowded theater as a good thing. It was called Smell-O-Vision. And, oxymorons aside, the process involved releasing different scents (hidden in containers beneath seats) into the air that would help identify characters and plot points to audience members before dissolving away moments later with plenty of time for the next smell.

Here, in a widescreen wet dream for osmologist filmgoers, the late Denholm Elliott (whom an entire generation knows only as Marcus Brody from the original Indiana Jones franchise) portrayed a English mystery writer on vacation in Spain who gets entangled in a web of espionage when he realizes an American heiress is in mortal danger. Trouble is, he doesn’t know what the woman looks like; identifying her only by her very expensive (and delightful) perfume. In an effort to track down the endangered lass, he enlists the assistance of a deadpan, wise-cracking, rotund taxi driver (a part that could only be filled by Peter Lorre, who loved stealing scenes as much as his co-star, thus making for a unique screen pairing) and the two trek across the countryside of Spain, where, shockingly, the rain does not fall anywhere.

Sadly, and perhaps for what should be quite painfully obvious reasons already at this point, Smell-O-Vision never really took off. In fact, it sort of bombed. Oddly enough, there were actually a few other attempts at delivering the same kind of weird end, such as a rival process called AromaRama. Again, these too failed to present patrons with a lasting impression. By the time 42nd Street reached its glory days of the grindhouse era in the ’70s, such a gimmick was no longer necessary, as an average visit to any cinema served up its own venerable array of possible – and sometimes inconceivable – odors either emitted, excreted or ejaculated by the interesting denizens that frequented such establishments for purposes other than actually watching the movies that were playing there.

Today, Smell-O-Vision sounds like the joke that it really was, living on for future generations to briefly chuckle or become befuddled about solely in a vicarious sense. John Waters’ 1981 black comedy Polyester presented viewers with a scratch-and-sniff card as part of its illustriously satirical Odorama process (though those cards really did work; so much so that the original DVD release of the film included a recreation of the offensive option for those who wanted to enjoy the full experience). A memorable moment on landmark comedy series SCTV once found “Monster Chiller Horror Theater” host Count Floyd (Joe Flaherty) introducing a movie in Smell-O-Rama in a bumper promo, only to torture himself with the deplorable fetor produced by the evils of an unmarked aerosol can he tried to urge kids to go down and pick up at their local convenience store.

I suppose it’s safe to say the ends justify the means in this instance. Strangely enough, and here’s where it somehow gets even more interesting, the ill-fated Smell-O-Vision would not spell out the end of the feature film I was really supposed to be commenting on all this time, Scent of Mystery. After its parental gimmick resulted in the film being pulled, it was all-but licensed (and later sold to and buried by) yet another gimmick rival, Cinemiracle: the bastard cousin of the much more notable Cinerama. Cinerama itself was a process that emerged audiences into one movie presented onto a giant curved screen via three projectors; perhaps the most quintessential example of the lengths Hollywood went to in order to get people back into theaters once television took over in the ’50s.

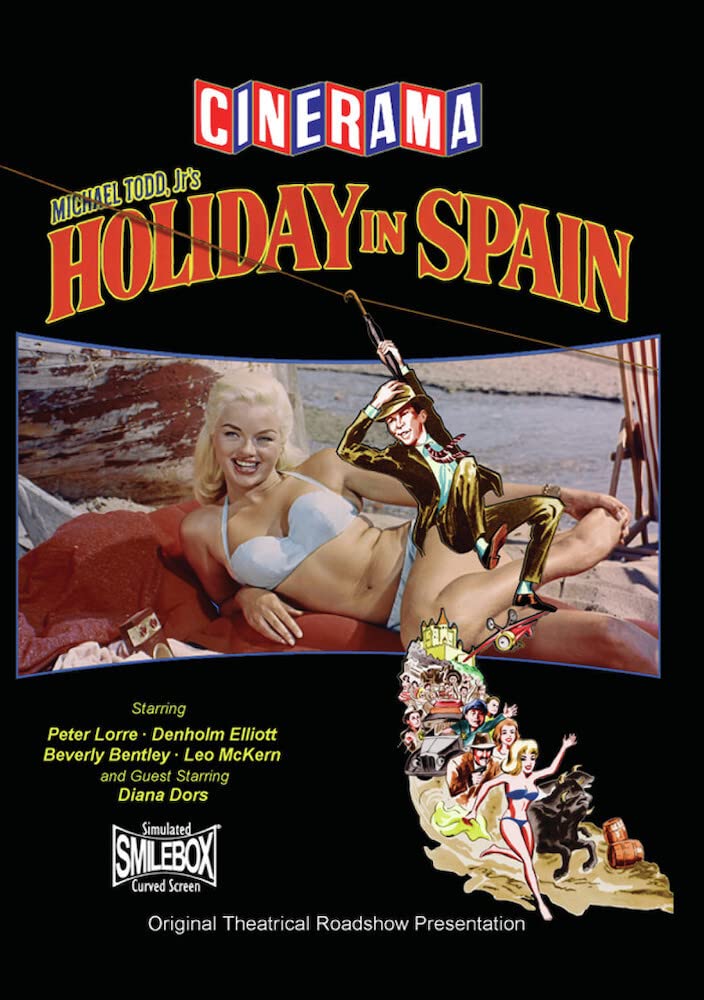

Thus, at least one year after its pungent smell dissolved into the air, Scent of Mystery (which really isn’t that bad of a title, in my opinion) made a second debut, this time in a re-edited redux that had been retitled Holiday in Spain. And it is this secondary cut that has been remastered and reconstructed for an all-new Blu-ray presentation courtesy the folks at Cinerama and Redwind Productions, who have done their utmost to recreate the original Cinerama experience of the failed film’s second release. Technically, it is the only version of the film that still technically “exists” with the exception of the odd VHS bootleg of a truncated cut that aired on MTV during the early ’80s that was something right out of a showing by Count Floyd himself: it was presented in conjunction with a 7-11 where viewers had to go in order to obtain their scratch-and-sniff cards! (Is that a case of art imitating life, or do I have it the other way around?)

But I digress. Among the various weird steps taken in the creation of Holiday in Spain were the excising of at least two reels of footage and the inclusion of some very solemn and sardonic narration from the good Mr. Elliott, who was brought back in (probably against his better judgment). Said voiceover is barely audible on some occasions, and its placement over certain “dramatic” or “action” scenes almost sounds as if it is recreating another theater experience: that guy a row or two back who talks over every scene. The movie’s tendency to linger entirely too long on objects originally intended to trigger a targeted scent causes some confusion, needless to say; who knew freshly-baked bread was so appealing to cameramen, or that the contents of a keg of wine can flood a steep street that well?

Nevertheless, the new title of the movie fit right in with most regular Cinerama releases, which often took white-bread American audiences to exotic international locales full of weird foreign people and their weird foreign customs. Holiday in Spain features numerous moments of long drives through the scenic countryside from the dashboard’s view, and various celebrations/rituals enjoyed by the locals. But despite its own faults, Holiday in Spain sets itself apart from those other travelogue films by having much more of a plot. Sure, it’s a weak one, but if this is the only way we can see two such distinguished, polar opposites as Denholm Elliott and Peter Lorre on an adventure together, then so be it: count me in. Appearances by Diana Dors, Peter Arne, Paul Lukas, Liam Redmond, and Leo McKern, a theme song performed by Eddie Fisher, and a cameo by a certain celebrity of the time only sweeten the deal.

Cinerama/Redwind Productions’ Blu-ray release of Holiday in Spain was taken from several sources: one a 65mm negative that wasn’t in the best of shape, and two different 70mm prints that had faded over the years. And it was with these three elements combined with some amazing modern technology and a whole heap of patience and determination that remastering director David Strohmaier has managed to pull off what some would deem impossible. With faded colors restored and damaged elements repaired as best as can be, Holiday in Spain now makes its home video debut, and the final product is something that deserves your attention just for the sheer amount of hard work put into it if nothing else.

The main feature is presented here with a new DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 mix that was constructed from the film’s original 6-track magnetic stems, and is a feat in itself. A secondary audio selection is on-hand in the form of an audio commentary by Strohmaier, who is joined by actress Sandra Shahan, with the session being moderated by the one and only Bruce (The First Nudie Musical) Kimmel. Several featurettes are also included, which range from Strohmaier visiting some of the movie’s filming locations today; missing scenes from the 70mm version; interviews with actress Beverly Bentley and Mike Todd Jr.’s daughter, Susan Todd; a look at the remastering process; a slideshow; and finally, a collection of Cinerama trailers.

The set also boasts a recreation of the original roadshow program used for showings of Scent of Mystery as well as an exclusive CD soundtrack of Mario Nascimbene’s score from that first incarnation of the movie, produced and released by Bruce Kimmel’s label, Kritzerland.

Is this all a bit excessive for an extremely minor motion picture that has been (somewhat rightfully) forgotten by the world and its inhabitants? Perhaps. But as I said before, there has been a lot of care issued to this tiny little footnote of a film by just a handful of adoring fans. That in itself says something. It definitely shows us something. Why, it even smellslike something. No, it’s not teen spirit, kids, that’s the smell of love; love for a weird, goofy little gimmick flick. And that’s enough for me to recommend this Blu-ray/CD oddity wholeheartedly right there.