The sky is a pale blue. Big, white clouds float by. It looks peaceful. It won’t for long. This is the view from the Enola Gay on August 6, 1945, the day the United States of America dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan. A narrator tells us how the plane left early that morning. About how the pilot Paul Tibbetts had doubts about what he was doing. We see the Hiroshima approach in the distance. The narrator tells us of the destruction of that day. How the bomb killed thousands upon impact. How it leveled the city.

The view changes, and we’re in a classroom now. The narrator’s voice is coming from a documentary the children are listening to. It is not August 6, but sometime later. A young girl says she doesn’t feel well and faints. She is taken to the hospital where they learn she has the “A-Bomb Sickness”. Sometime later, back in class, the teacher apologizes to the students. He isn’t from Hiroshima and he hasn’t taken the after-effects of the bomb seriously. But now he has read, studied, and seen how more and more people are getting sick from it. How they are dying.

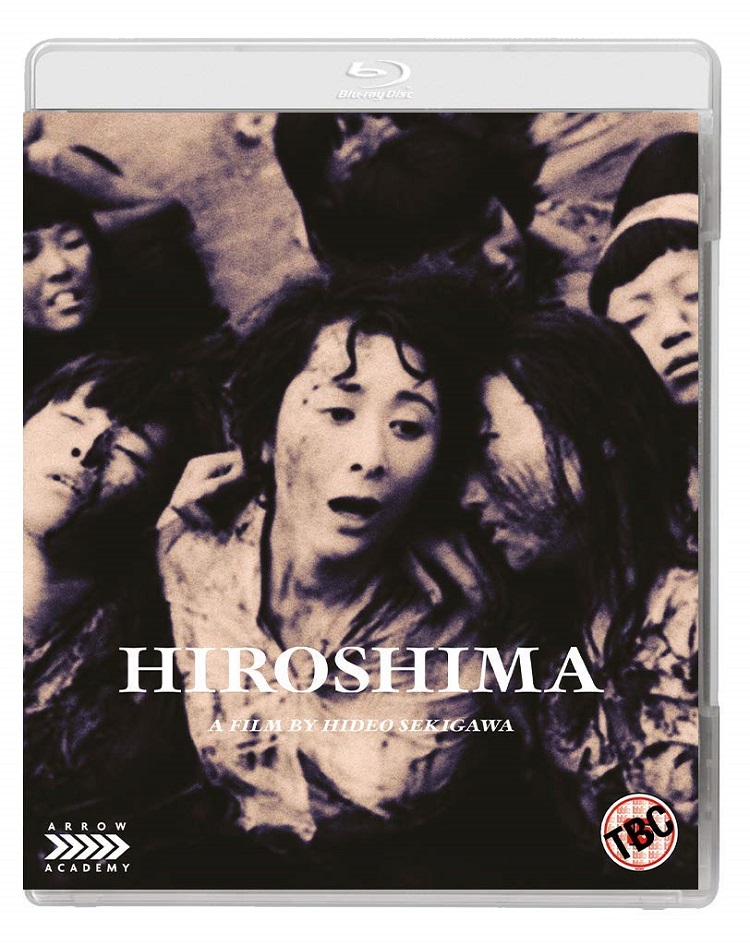

Hideo Sekigawa’s 1956 documentary-style narrative film Hiroshima tells the story of the first atomic bomb explosion used in combat and its horrific effects on the Japanese people. Incorporating real documentary footage into his narrative gives his film a realistic and very difficult to watch feel. It moves from the classroom to a more idyllic setting. Adults and children work outside on a beautiful day. They are farming and building something. They smile and. A woman looks at the flowers and is happy.

Flash. Bang.

Everything is gone. All the houses and buildings are rubble. The people are on the ground dead and dying, covered in dirt and blood. For the next twenty minutes, the film moves across the city detailing the horror of the events following the detonation of the bomb. It is overwhelming.

A group of children lay beneath whats left of their school. The teacher, trapped under a beam, calls out to calm them. Shout your name, he says, if you can hear me. A woman is trapped in another building, half her body caught under bricks and rubble. Her husband desperately tries to push a rafter off of her. No, she says, leave me be, go look for our children. The man runs outside for help. He calls after a soldier, but his cries fall on deaf ears. Everyone is in shock. The solider’s clothes are ripped, his face bloody. He walks on. The building has caught fire and the man listens to his wife scream as she dies. Several women swimming in a river gather around each other. They hold onto one another and sing. Slowly, one by one, they let go floating away. Dead. The river is poisonous.

On and on it goes from one scene of terrifying horror to another. Babies cry near the corpses of their dead parents. Fathers and mothers desperately look for their children. Everyone is hurt. Everyone is confused. People are dropping dead all over. It is a scene far more horrific than any horror film. It is unrelenting and hard to watch.

The film moves away from the immediate horror to a committee discussing what Japan should do next. The scientists declare that Japan should surrender immediately, the soldiers cry out that they should never give up. Outside makeshift hospitals have been set up and doctors try to help ease the suffering. Time passes. People have learned they can swap blankets for rides on boats out of the city. Children are taught how to say “hungry” to the foreigners coming now in droves. They don’t know what it means but they know if they say it they will be given chocolate and bread.

They try selling bits of rubble where you can see burn marks left by the bomb. An older boy shows them how to find bomb shelters where you can find the skeletons of the dead. Foreigners will pay good money for that. The war may be over, the initial horror has ended, but survival is not guaranteed.

Because the film chooses to not focus on any one individual or to give us any indication of who these people are, these scenes, harrowing as they are, can feel a little overwhelming and long. It is like watching nameless people go through hell. It is something everyone should watch once and then never again.

In a new video essay by Jasper Sharp, included on this Arrow Academy release of the film, there is some discussion about how during the American occupation of Japan after the war, video footage of the effects and aftermath of the bomb were carefully censored. Meaning the average Japanese citizen had limited knowledge of what exactly had happened to them. This film was made just after the occupation had ended. I can’t imagine it was easy viewing for those who had survived if any of them watched it. It wasn’t easy viewing for me sitting comfortably in my nice, middle-class American home worrying over the effects of Covid-19 that has mostly left everyone I know untouched. But it is an important document of its time, one that helped show just how horrible the bomb really was.

There are now hundreds of documentaries about the bomb. If one so chooses, one can be inundated with information about the war and the Hiroshima bomb. In that sensem Hiroshima the film seems unnecessary. But in another way, it is just as important now for it gives a real feeling of what it must have been like, what it must have felt like to be there in the way only narrative films can. I can recommend that it should be seen by everyone, but you must be prepared for it. And I can’t imagine anyone wanting to watch it a second time.

This Arrow Academy release comes with a new 1080p transfer, with the original uncompressed audio (a special shoutout should be given to Akira Ifukube who wrote the incredibly haunting music. A few years later he would score Godzilla.). Extras include an archival interview with actress Yumeji Tsukioka, a 73-minute documentary featuring interviews with survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings, a video essay by Jasper Sharp and the usual full-color booklet with an essay about the film. The extras really help put both the film and the bombing into a larger perspective. They are worth the purchase even without the movie.