There’s a little cottage industry of documentaries about movies that didn’t get made. Every few years one of them pops up – Lost in La Mancha about Terry Gilliam’s early, disastrous attempt to make The Man Who Killed Don Quixote or Jodorowsky’s Dune. Implicit in the premise is that the world of cinema is missing out on a masterpiece – that a world of perhaps game-changing potential is lost to us because of some unfortunate timing, a couple of bad days on a set, or a miscalculation that metastasizes into a disaster.

Honestly, whenever I see or read these stories, and watch the in-progress footage or hear the raw ideas, almost invariably, I think, “This thing looks terrible.” Watching Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Inferno, a documentary that for the first time shows extant footage from a troubled production that culminated in the main actor walking off the set and, days later, the director having a heart attack, it sometimes seems that the film’s failure to get off the ground might have been better for all involved.

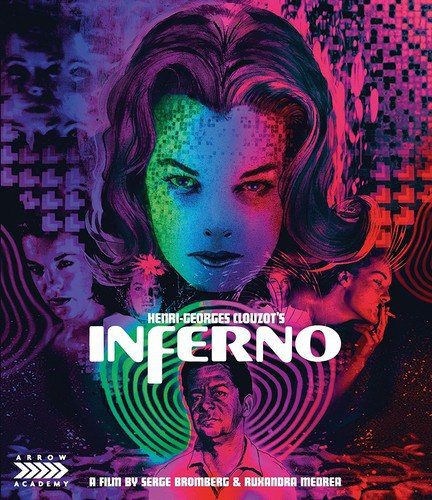

Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Inferno is a film by Serge Bomberg and Ruxandra Medrea Annonier released in 2009, 40 years after the troubled shoot. It tries to do two things at once – to tell the story of the film’s production and how it collapsed, and to present, as much as possible, an idea of how the film would have turned out. Several scenes from the film are dramatized by two actors, with actual footage from the 1964 shoot interspersed with their dialogue. Apparently no soundtrack from the shoot survives at all, so much of that is recreated as well.

Henri-Georges Clouzot is perhaps most famous for his two great films of the 50s – Wages of Fear, and Les Diaboliques. He was a master of wringing tension from a shot, and had a visceral visual style. Inferno, titled L’Enfer in France, was going to be Clouzot’s exploration of pathological jealousy, about a man on vacation with his wife who becomes obsessed with the idea that she was cheating on him, either with the handsome man in town or maybe that man’s girlfriend. Clouzot wanted to depict the distortion of reality that occurred as the lead’s monomania takes him over, as well as to make his filmmaking relevant to the younger new wave directors that were coming to prominence in mid-60s French cinema. To do so he put together an ambitious team of cinematographers and visual effects artists to create different in-camera effects. All kinds of double exposures, filming through water, playing with moving lights over actor’s faces were tried, as well as different make-up effects that would then be printed in such a way that the actors skin color would fade, and details would stick out.

It looks bizarre, and strange, and for every one effect that has a distinct psychological effect, there were several others that were just confusing, irritating, or downright silly. Watching the comely Dany Carrel writhe around topless in a transparent cellophane smock is fun, but I doubt it would have had the impact Clouzot might have been looking for.

But that’s the inherent problem in watching recreations of what might have been – none of these effects were shot in actual scenes. It was, as far as I can tell from the documentary, all test footage that was going to be used as the basis of real scenework in an extended shoot in studio.

The typical narrative of film failure usually involves producers hemming in the artistic vision of the director. On L’Enfer, the opposite seems to be the case. Investors offered Clouzot essentially a blank check. The cast was filled with stars, including Romy Schneider and Serge Reggiani. Henri-Georges Clouzot wrote much of the script himself, and so he went about making the exact movie he wanted in the exact way he wanted… and failed. Scenes that had been completed were constantly reshot. Three camera crews were employed to speed up the production, but Clouzot insisted on over-seeing every step of their work, essentially wasting the potential time savings. The “perfect” location he picked was a hotel on an artificial lake that was scheduled to be drained in less than a month.

Why did Clouzot set himself up for such a prodigious fall? That question this documentary does not answer. It offers interesting anecdotes about the way that Clouzot would work, though they mostly scratch the surface. The man himself died in 1977, 13 years after this disastrous shoot and only made one more film in his career. We’re left wondering what this failure meant to him personally, to his career and to the future of his filmmaking. Henri-Georges Clouzot end with the production ending, but simply doesn’t tell the whole story. It’s interesting, sure, but not probing.

Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Inferno has been released on Blu-ray by Arrow Academy. The transfer looks remarkable, in particular the old film footage looks surprisingly pristine for a bunch of film cans that had just been sitting around. The extras are typically copious and interesting: there’s an introduction to the film by director Serge Bromberg, as well as a 18 minute interview, both of which discuss how the film was tracked down and what they were trying to do, blending the documentary and drama. There’s a 21 minute discussion of Clouzot and L’Enfer by Lucy Mazdon. Most extensive is the hour-long featurette “They Saw Inferno”, which includes more unseen footage from the film’s production, including numerous test shots of proposed visual effects. There’s also an essay about the production in the booklet by Ginette Vincendeau.