Larry Cohen, the writer-director of such cult faves as It’s Alive, Q: The Winged Serpent, and The Stuff, was a force—a genuine talent. His 1975 sci-fi-horror comedy procedural, God Told Me To (a.k.a. Demon), is a fascinating mélange of tones and ideas, but it’s disjointed. It’s not laugh-out-loud funny. It’s also not scary, and it’s not as suspenseful as it wants to be. Neither good nor so-bad-it’s-good, the movie is both dull and unsettling.

And it’s the most bizarre grindhouse movie I’ve seen in many a moon.

Tony Lo Bianco stars as Peter Nicholas, an NYPD detective who investigates a series of murders committed by ‘normal’ folks who say, “God told them to.” (One of whom is a cop—that Andy Kaufman plays!) Nicholas, a Catholic with a lover (Deborah Raffin) and an estranged wife he won’t divorce (Sandy Dennis), doubts his faith, even his origins. Murder clues lead him to a prophet-like figure and talk of alien abductions. Will he plunge into a rabbit-hole of religious mania? Has he encountered the person or persons orchestrating these crimes? Has anyone orchestrated them? He and we must face these questions.

Shot mostly on the streets of New York City, with cheap-looking FX, God Told Me To has a real creeper somewhere inside it. As it stands, though, Cohen’s ideas don’t translate to a seamless experience. In the hands of a different stylist with a larger budget, the film could have amounted to something more. Yet it’s just as likely the film wouldn’t have felt so raw, so immediate. At play is a gritty street realism that might be the film’s chief asset. It thickens the texture. The movie hooks us with its dark presentation of an urban police procedural.

But then it… goes off the rails.

Depending on your taste, this could be welcome. The main confrontation occurs between Nicholas and a long-haired dude, Bernard Philips (Richard Lynch), who lives in the basement of a dilapidated tenement. Who Philips is or claims to be, and the junk that he mumbles about revolution, forms the nutty basis of the rest of the film. (In Cohen’s hands, the Spear of Destiny that pierced the side of Christ gets a new twist.) For me, this weirdness (and the movie’s fixation with it), while kooky as hell, doesn’t further our emotional involvement in the story. It doesn’t pay off the set-up.

That said, if you give the movie half a chance, it might crawl under your skin. Cohen’s concept of an indifferent, pitiless deity—manifested by a whack-job messiah who doesn’t mind if the ‘sheeple’ kill each other (who might even encourage it)—and the cover this provides an entire populace to justify its wish to snap (to cave into their base instincts and revel in the grime and the insanity) charges the movie. Cohen goes for it, too: leaning hard on graphic violence—zooming in on quivering orifices—he delivers a pre-Cronenberg, Cronenbergian mind-fuck of a film. Each time I was about to doze, the exploitative zeal with which Cohen visualizes the story pinched me awake. More important, these moments of shock serve a purpose—they underline the film’s obsession with our gift for torturing ourselves with repression and guilt. With the fact that, whether it’s 1975 or 2022, we all look for a release valve. A cause we can get behind, to not go nuts. Or indeed, (faced with the eternal void and the boiling suspicion that nothing cures the loneliness and rage that fuel our lives), a cause that lets us go berserk.

To a point, this is fine; but when the movie goes bug-nuts, Cohen loses control of the narrative. Any suspense he’d built evaporates, and the movie leaves us with the promise of a tighter, more emotionally gripping story. Credit Lo Bianco, though, as his presence works in the movie’s favor. As Cohen’s ambitions spike (and then unravel into something gloriously absurd), Lo Bianco holds his own. The strength of his portrayal is a solid counterpoint to the inane moments that sometimes drop in abruptly. Other actors do good work as well, especially Sylvia Sidney (as the mother of Nicholas’s main suspect) and Robert Drivas (as a man who calmly explains to Nicholas how one day he woke up, threw on his robe, and killed his entire family, because God told him to). These performances help fire the unsettling mood of the film.

As a ragged, jagged combination of elements designed to provoke the viewer, God Told Me To is not without impact. But Cohen’s reach exceeds his grasp. He has ideas, and he doesn’t flinch from the sheer nuttiness of the story. The movie remains a big, misshapen lump of morbid fascinations. You could say it inches into blasphemous satire. You could say its depiction of a soul-sickened, faith-starved city that has lost its grip leaves a queasy aftertaste. And perhaps its freefall from a police procedural into a bold, delirium-choked narrative is refreshing. These views are valid; but something in the execution prevents the movie from being a viscerally satisfying experience. Chalk it up to Cohen’s zigzag approach. Tonally, he’s just overspread and under-baked (or the reverse, I can’t tell).

For now, I’ll summarize. This is a crazy, cross-genre film with guts and grit, a movie I wouldn’t say I enjoyed but one from which I couldn’t look away. Because… wait for it…

God told me to.

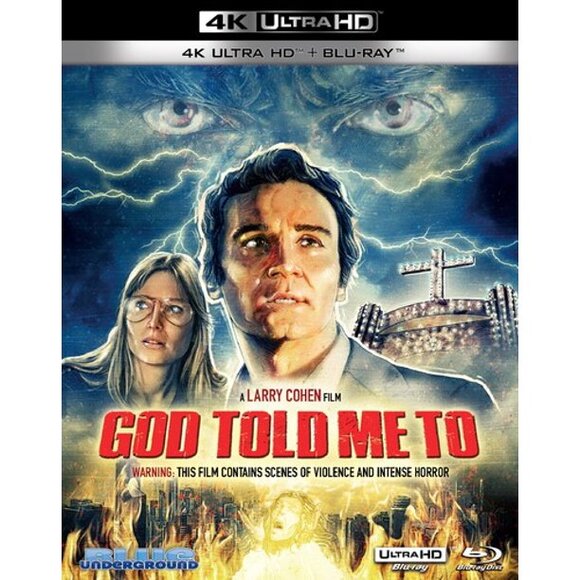

The new 4K release from the good, freaky folks at Blue Underground looks and sounds great. Special features include audio commentary by Cohen and another one by film historians Steve Mitchell and Troy Howarth. You get a couple Q&As with the director, a present-day interview with Lo Bianco, a few promotional spots, and a poster and still gallery. If you’re a fan of the movie, don’t wait for God to tell you to spend your hard-earned pay on this set. Or do and see what happens.